Written in July 2008 for an issue of Stop Smiling devoted to Washington, D.C. In a way, the recent Arrival might be said to qualify as a mystical remake of The Day the Earth Stood Still, and I found it every bit as gripping. — J.R.

To get the full measure of what Cold War paranoia was doing

to the American soul, two of the best Hollywood A-pictures

of the early 50s, each of which pivots around its Washington,

D.C. locations – The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951) and My

Son John (1952) — still speak volumes about their shared zeitgeist,

even though they couldn’t be further apart politically.

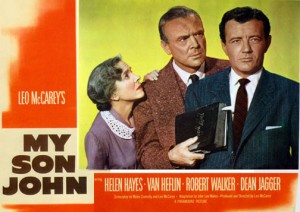

An archetypal liberal parable in the form of a science fiction

thriller and an archetypal right-wing family tragedy (with deft

slapstick interludes) that’s even scarier, they’re hardly equal in

terms of their reputations. Leo McCarey’s My Son John, widely

regarded today as an embarrassment for its more hysterical elements,

has scandalously never come out on video or DVD [2014 footnote, it’s

now available from Olive Films], though in its own era it garnered

even more prestige than Robert Wise’s SF thriller, having received

an Academy Award nomination for best screenplay. It also features

the last and in some ways richest film performances of both Helen

Hayes and Robert Walker. (Although she lived another four

decades, Hayes chose never to act in a feature again [July 2015: a

reader, Scott Moore has just rightly informed me that this is far from

correct], and Walker died unexpectedly while My Son John was still

being shot, from an overdose of the sedative sodium amytal,

administered by his doctor in ambiguous circumstances.)

At once profound about the dynamics of family discord

involving cultural differences and deranged about the Communist

menace, My Son John shows with equal sincerity and intensity

McCarey’s complex understanding of people and his unqualified

support of the FBI’s totalitarian surveillance of his most sympathetic

character (Hayes), when she confirms what they already know —-

that her favorite son (Walker), John, a Washington bureaucrat, is a

Communist agent. When she finds that a key in John’s trousers

unlocks the Washington flat of another agent (a character based on

the spy Elizabeth Bentley, who defected and gave names at an

HUAC hearing in 1948), at least four concealed cameras by

“caring” agents are needed to capture every nuance of her private

grief.

The Day the Earth Stood Still, still rightly considered a

classic in everything from its Theremin-enhanced

Herrmann score to its fine pacing and performances,

continues to be pointed and timely — and not only because

Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977) was clearly

indebted to it. Adapted loosely by Edmund H. North (whose

previous credits included Young Man with a Horn and

In a Lonely Place) from a Harry Bates story, it recounts the

landing in Washington of a flying saucer with a benign alien

named Klaatu (Michael Rennie). Tall and wise, he carries a

universal message of peace for all mankind, but trigger-happy

Cold Warriors imprison him and then much later, after he

escapes and moves through Washington incognito, shoot him

before he can deliver his message.

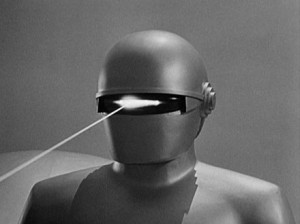

He then has to be resurrected by a giant robot-protector who

guards his flying saucer; he also has to shut off most of the

electricity in the world for half an hour in order to get

everybody’s attention, which accounts for the movie’s title.

Thanks to his human appearance, Klaatu can initially roam

the streets of Washington undetected under the name

Carpenter (one of the movie’s touches of Christian allegory).

His only human allies prove to be a local widow

(Patricia Neal) and her 13-year-old son (Billy Gray) — his

landlady and local tour guide, respectively — and a gentle

physicist clearly modeled on Einstein (Sam Jaffe, whom

part of the studio brass at 20th Century-Fox tried to remove

from the project due to his leftist background).

Producer Julian Blaustein has said that the film’s progressive

slant was inspired in part by the absurdity of such everyday Cold

War terms as “peace offensive”. That the movie isn’t exaggerating

the crazed paranoid climate of its era can perhaps be seen most

readily in the willingness of real-life radio newscaster Gabriel

Heater to play himself, broadcasting his conviction that

Klaatu has to be “hunted down like a wild animal” as soon as he

manages to escape from the clutches of the U.S. military. By the

same token, what seems most dated and naïve about the film is

also what’s most typical about it —- the fact that an advanced

extraterrestrial civilization would choose to address the entire

world by landing in the U.S. capitol and proceeding no further.

No less typically, the movie’s Washington locations —-

including many familiar standbys, such as the Lincoln Memorial

(duly admired by Klaatu) and the nearby Arlington Cemetery —

were filmed by second unit, as they were in My Son John,

although this is so skillfully done that you may not always

notice it. (Speaking years later, as an adult, Billy Gray — who

describes this film as the one he’s in that he’s proudest of —-

recalls how disappointed he was as a kid about not being able

to travel to Washington.)

My Son John uses the Lincoln Memorial even more centrally,

as the site where John dies after he splits from the Party and

then gets machine-gunned by his former comrades from a

passing car, causing his cab to flip over on the Memorial’s

steps. An association of Robert Walker with this hallowed

spot was already made in The Beginning or the End, a

1947 docudrama about the development of the Atomic

bomb, where he played one of the pilots who dropped the

bomb on Hiroshima, and later turns up at the Lincoln

Memorial to reflect on the meaning of it all. And he could

later be seen in many other D.C. locations when he played

the creepy villain in Strangers on a Train (1951), decked

out with various stereotypical gay mannerisms and

accoutrements —- a bold casting coup on the part of Alfred

Hitchcock when one considers that Walker had previously

been known for his conventionally “wholesome” romantic

roles in films such as The Clock (as Judy Garland’s costar)

and Till the Clouds Roll By (as composer Jerome Kern).

Somewhere in Middle America, 500 miles from Washington, lives the

upright and aptly named Jeffersons of My Son John: Dan (Dean

Jagger), the jingoistic and frankly dumb father; Lucille (Hayes), the

more liberal and high-strung mother; and their three sons —- two

football jocks preparing to leave and fight in Korea in the opening

scene, and John, the only absent family member and the best

educated, an intellectual who’s grown apart from the others and

now works in Washington in an unspecified government job. As

Lucille boasts to a stranger (who later turns out to be an FBI agent

named Steadman), “He has more degrees than a thermometer.”

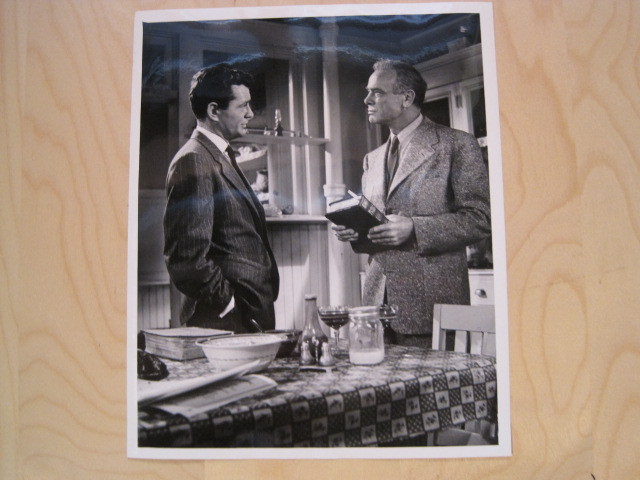

The story proper starts when John finally comes home on a

visit and his parents gradually and painfully discover he’s

become a secret agent. But even before that discovery is made,

mainly through the good graces of Steadman (Van Heflin) —-

as wise and benign as Klaatu, though short rather than tall —-

John’s uneasy banter and half-concealed sarcasm already marks

him as a not-so-benign alien, someone clearly preferring the

company of his former professors to that of his family or their

local priest. (In The Devil Finds Work, James Baldwin

praises Walker’s “gleefully vicious parody of the wayward

American son,” which he finds “absolutely heartless and

hilarious, acting out all of his mother’s terrors, including,

and especially, the role of flaming faggot, which is his father’s

terror, too.”) He’s much closer to Lucille than he is to Dan

—- who actually hits John on the head with Lucille’s Bible

in one moment of rage. Yet when she innocently asks her

son, “You got a girl?”, he can only respond, “Well,

sentimentalizing over the biological urge isn’t really a

guarantee of human happiness, dear.”

Though Walker was far too skillful to give the same performance twice,

the sinister aura he acquired from Hitchcock was partially carried over

into John, where the suggestion of gayness is conveyed more by the plot

(John’s “dirty” secret) than by any overt mannerisms. McCarey falsely

claimed after Walker’s death that he’d already completed his work on the

film, out of fear that its commercial success would be jinxed, meanwhile

undertaking a frantic, intricate, and far-fetched revision of the story that

involved, among other things, matting in silent images of Walker from

Hitchcock’s film, killing off his character at the end, and even dubbing

John’s final words himself, spoken in an eerie whisper. Originally, John

was supposed to give the commencement address at his alma mater

after his (improbable) recanting, and in preparation for this scene,

Walker recorded the speech on tape shortly before his death. McCarey

then had John do the same thing so that his speech on tape could be

played back at the commencement in the final sequence.

Demonizing respectively Cold Warriors and Communists,The Day the

Earth Stood Still and My Son John might be described as cautionary

tales about the perils of thinking too little and thinking too much. The

thoughts are richer in the first, but the feelings count for more in the

second.