Chapter Two of my book Movie Wars: How Hollywood and the Media Limit What Films We Can See (Chicago: A Cappella Books, 2000). The cover below is that of the U.K. edition published by the Wallflower Press. — J.R.

How often are aesthetic agendas determined by business agendas? This question is not raised often enough.Terminology plays an important role here. For example, once upon a time, previews of new releases were called “sneak previews” because the titles of these pictures weren’t announced in advance. Most industry people continue to use the term, despite the fact that the titles are announced and even advertised, so that the original meaning gets obfuscated: the only thing “sneaky” is the fact that they’re called “sneak previews.”This is a relatively trivial example of how terminology alienates us from what goes on in the world of movies. A more significant example is how we use an extremely loaded term like “independent.” An independent filmmaker traditionally meant a filmmaker who worked independently, free from the pressures of the major studios. If you believe what the media say about independent films, then the mecca for independent filmmaking would be the Sundance Film Festival, an event where independent films and filmmakers congregate annually. But the festival was started by a prominent movie star, Robert Redford, and has been dominated for years by studio producers, studio‐owned distributors, and agents with strong ties to the studios. For independent filmmakers to “succeed” at Sundance almost invariably means selling their films to studios — which means in most cases losing control, including final cut. Ergo, to succeed at the mecca for independent filmmaking is to lose one’s independence. It’s as simple as that, but you rarely if ever find an acknowledgment of this in the media celebrations of Sundance (many of which take place in The New York Times, which for years has been one of Sundance’s corporate sponsors). Instead you hear about the prize catches of “independent” companies like Miramax (a company owned by Disney) and October (a company that until recently was owned by Universal): Quentin Tarantino or Kevin Smith, for example.

***

When it comes to the role of business in shaping cinephilia, criticism is often simply in denial. How much do commentators on the French love of American cinema after the war factor in the crucial part played by the Marshall Plan in making sure that this American cinema was available in profusion in France, and not necessarily because everyone wanted it? When dealing with new versions of movies labeled “restorations” and/or “director’s cuts,” how often do critics bother to ascertain the accuracy of these claims? (Sometimes a “restoration” means simply striking a new print, and sometimes — as in the case of the new version of Orson Welles’s Othello, discussed in Chapter Nine — it means effacing and altering the original. No less often, reinserting material that a director deliberately omitted yields what many publicists call a “director’s cut.”) And when it comes to film cults, how often is it acknowledged that their existence depends on a system of independent exhibition that is practically extinct nowadays?

To understand a few basic facts about both cult films and art films in the United States, it is helpful to sketch in a little bit of economic history. In 1938, the U.S. government filed an antitrust action against Paramount Pictures, objecting to the monopolies of movie theaters held by the studios; by the end of 1946, a court judgment enjoined not only Paramount, but also Loew’s, RKO, Warner Bros, and 20th Century-Fox from acquiring additional theaters and engaging in other anti‐ competitive practices prohibited by the Sherman Antitrust Act, such as blind bidding, forced rentals, and refusing to rent certain films to certain exhibitors. This had many consequences, the most important of which was a substantial reduction in the control of the Hollywood studios over what moviegoers saw in theaters. Paramount, which controlled the largest of all the studio‐run theater chains, had nearly fifteen hundred theaters operating in the late forties. In 1953, their theaters were purchased by American Broadcasting Companies, Inc. — ABC television and radio — but because of all the sales of theaters required by the government decree, this chain was reduced to a little over five hundred theaters by 1957. By the late fifties and early sixties, the more equitable and open market for movie exhibition created by these rulings led to more independent theaters, including art houses that specialized in foreign films and, by the early seventies, midnight movies.These flourished on the basis of films being rented for a flat fee rather than on a percentage basis, granting a lot of creative freedom to individual exhibitors and programmers.

After the studios were forced to sell off most of their theaters, they used five methods of licensing or distributing movies: competitive bidding, competitive negotiations, non-competitive negotiations (limited to areas with only one exhibitor), tracking (an exclusive arrangement worked out informally between a distributor and a particular exhibitor), and splitting (an agreement among exhibitors about who would negoti ate initially for a given film: after distributors sent out competitive bid letters, only the designated exhibitors would bid on the film, the others awaiting their turns). The latter two methods were the ones most commonly used in the fifties, sixties, and seventies; although they were challenged on occasion, the courts found them to be an efficient means of preventing the wealthiest exhibitors from cornering the market.

In April 1977, the Justice Department reversed its thirty‐year position and declared splitting to be an illegal form of rigging the licensing of pictures. The federal court in Virginia where the Justice Department brought suit, however, decided that if distributors acquiesced in splitting arrangements then they weren’t illegal. In the early eighties, the Justice Department again challenged splitting, this time among the four largest exhibitors in Milwaukee, and on this occasion splitting was declared illegal, a position affirmed by the federal appeals court in Chicago in 1985.

Over the next couple of years, the Justice Department imposed heavy fines on several exhibitors nationwide for splitting, a move that put studios in a better economic position to handle exhibition. Then, in 1988, Warner Brothers petitioned the federal district court in New York for an order modifying its antitrust decree, allowing Warners to join forces with Paramount in taking ownership of Cinamerica Theaters — a chain encompassing over a hundred movie houses, including the Mann chain — and after a year‐long review the Justice Department, under the Reagan administration, allowed them to go ahead. When the federal appeals court in New York affirmed this decision and made it even more conclusive by being nonrestrictive, the argument they used was that allowing the studios to compete with distributors — many of which came into existence thanks to the economic boom of the eighties — was only fair, because the studios had been under the thumb of the courts and the distributors weren’t.(1)

My own cinephilia arose from the fact that I grew up in a family in Alabama that ran a chain of movie theaters. Curiously, however, I was the only member of my family who qualified fully as a cinephile, then or now. My grandfather, who started the business, enjoyed movies but was no aficionado, and my father, who worked for him, was usually far from passionate about seeing them; he preferred to read books. My three brothers went to movies more often than most of their friends, but more out of habit than out of any sense of vocation.

My grandfather had partners in Tennessee who owned other theaters, and in the late forties the government, as a test case, sued him and his partners for holding a monopoly of theaters in that part of the South. As a consequence the partnership had to be dissolved, and my grandfather’s chain became reluctantly independent in 1956; it remained so until these theaters were sold in 1960. (By that time, I should add, my cinephilia was fully formed, and I had already left Alabama to attend school in the North.) During those last four years, these theaters probably showed more foreign-language pictures than they ever had before.

This is because during the same period, art cinemas, a particular example of independent exhibition, were springing up all across America. This movement was spearheaded by the enormous success of two Roberto Rossellini films in 1946, Open City and Paisa, each of which grossed close to a million dollars in the states — an enormous sum in those days. By the time my family’s business became Rosenbaum Theaters, there were hundreds of such art theaters in America, and by the late sixties — when the French New Wave and the popularity of other European directors like Michelangelo Antonioni, Ingmar Bergman, Bernardo Bertolucci, Federico Fellini, Miklós Jancsó, and Andrzej Wajda was already in full flower — there were over a thousand. (Although this seems to contradict my assertion in the previous chapter that many films by these directors flopped, the expectations of small businesses versus those of the large studios and corporations accounts for this discrepancy. By analogy, I’ve often marveled at the relative capacity of French publishers to print limited edition publications of a thousand copies or less and deem their efforts completely successful if these editions sell out.)

Films showing at these independent theaters were usually rented for a flat fee — unlike big Hollywood films, which were booked on a percentage basis, with the distributors collecting a particular fraction of the ticket prices. Many of these theaters eventually became repertory and revival houses, and during the seventies, they began to show midnight movies such as Night of the Living Dead, The Rocky Horror Picture Show, and Eraserhead — a form of exhibition that became possible only because the theaters were independent.

Within such a setup, it was even possible to experiment and develop certain tastes that otherwise might have never prospered. In the book Midnight Movies (Harper & Row, 1983; second edition, Da Capo, 1991) that I coauthored with J. Hoberman, there is a detailed account of how former distributor Ben Barenholtz kept Eraserhead playing in theaters at midnight for week after week and month after month before the film finally found its audience, thereby launching the career of David Lynch. There were only twenty-five people in the theater on opening night in New York’s Cinema Village in 1977, twenty-four the second night, but Barenholtz persisted and kept the film running for almost a year. A year later, Barenholtz opened it again in New York at the Waverly, where it more than doubled its first run — playing ninety-nine weekends through mid-September 1981, a run that ended only when the theater closed to build a second screen. According to Lynch himself, there was never a single point when the film simply “took off”: “It was a very gradual incline.” But it proved that persistence of this kind — which is possible only in independent theaters, at least according to the way most chains are run — can eventually reap spectacular dividends, especially when it comes to creating and developing new markets. And nurturing offbeat films remained possible even for certain movies that didn’t play at midnight. In the early eighties, when enough independent theaters were still around, Dan Talbot of New Yorker Films was able to work comparable wonders with the arthouse releases of Wayne Wang’s Chan Is Missing and Louis Malle, Wallace Shawn, and André Gregory’s My Dinner with André — keeping both films playing in theaters week after week until they eventually attracted sizable audiences.

In spite of the gradual erosion of this practice, for reasons that I’ll get to shortly, there are still occasional films that manage to find their audiences over a period of weeks rather than simply over a matter of days. According to Ted Hope, cochairman of the independent production company Good Machine, Mike Leigh’s Life Is Sweet, released in 1990, did its best business during the eighth week of its run. Whether it had a ninth week isn’t something I’ve gotten around to researching, but independent pra movie would never get to its eighth week unless it was doing gangbusters.” She cites in particular Todd Haynes’s first‐rate Safe, which she produced: “By the time people were starting to talk about the film, it was gone from the theaters.”(2)

It was the proliferation of independent theaters in the fifties, sixties, and seventies that made the eventual success of an Eraserhead and a Life Is Sweet possible. In the eighties, however, the Justice Department under the Reagan and Bush administrations began to stop enforcing the antitrust laws in the manner described earlier; in Washington, D.C., I’m told, the antitrust division, which still exists as a ghost of its former self, is jokingly referred to as the “trust division.” As the market for independent theaters began to shrink accordingly, the alternative venues represented by foreign films and midnight movies became increasingly specialized and rarified, apart from the few foreign pictures that studio‐owned distributors such as Miramax decided to put their weight behind. Meanwhile, the growth of the so‐called “infotainment” industry over the same period — devoted to granting free publicity in all the media to studio product and practically nothing to anything else — has made the survival of independent movies and theaters even more precarious than it used to be. Finally, the recent decimation of the National Endowment of the Arts — which funds not only independent filmmaking, but nontheatrical distribution and exhibition — has more or less delivered the coup de grâce to practically everything except what the studios decide to shove our way. (The Blair Witch Project, boosted by alternative methods of advertising, might be termed the exception that proves the rule — a rare instance of a public demand forcing exhibitors to go along with it. One can only hope that other exceptions may also challenge the rules.) Even before this decimation, the U.S. government gave fewer and smaller grants to artists than almost any other industrialized country in the world; the annual grants given to military marching bands were bigger than all its arts grants combined.

While researching this chapter, I spoke with Chicago movie theater consultant Barry Schein and a representative of the National Association of Theater Owners (or NATO) in California, asking each of them how many independent movie theaters currently existed in the United States, and the difference between their responses was instructive. Shein told me that the fifty most powerful and successful American movie exhibitors had 47.2 percent of the locations and 76.5 percent of the screens, which breaks down to an average of 7.09 screens per location. The other exhibitors had 52.8 percent of the locations and 23.9 percent of the screens, which breaks down to an average of 1.5 screens per location. He added that in January 1999 — we were speaking the following July — there were 7,811 movie theaters in the United States with 34,186 screens, and that each year there was roughly a 1.14 percent decrease in theaters and a 6 to 8 percent increase in screens.

But when I asked the NATO representative, whom I spoke to the same day, how many U.S. theaters were independent, he replied that he couldn’t answer that question because the term meant so many different things to different people that it was effectively meaningless. Personally, I don’t see how “independent theater” could ever be meaningless, because the differences between an art theater showing independent features and a mall theater showing studio product are apparent to everyone. No matter how one defines “independent,” at least in relative terms there are fewer independent movie houses today than there were even before 1948. Today the major markets in American film exhibition are controlled and owned mainly by the Paramount‐Warners partnership, Sony (which owns Columbia/Tri‐Star and Loews), Matsushita (the parent of Universal, which owns half of Cineplex Odeon), United Artists Theatre Circuit, American Multi‐Cinema, General Cinema, Carmike, Cinemark, and National Amusements — in most cases, major corporations. In 1997, Sony merged with Cineplex Odeon, and although they were legally required to divest certain theaters, they still continue to rule most of the Chicago film scene monopolistically, without challenge from the Justice Department. On the other hand, even the handful of independent theaters that have managed to survive in the nineties are hampered by having to play ball with the studios to get some of the pictures they need to show in order to survive. In order to play a Pulp Fiction, for instance, they typically might have to show several other pictures handled by the same distributor. (Guess which one.) And to make matters still worse, the question of what is and what isn’t an independent feature has been thoroughly muddled by the media, by the distributors, and by the Sundance Film Festival, all these institutions often working in cozy tandem.

Now that truly independent features are becoming as much of an endangered species as independent theaters — a situation that so far seems only marginally improved by the runaway success of The Blair Witch Project — the game essentially belongs to movies that can prove their box-office mettle the same weekend that they open, whether these are independent or studio efforts, and in order to score in those terms, millions of dollars usually — if not invariably — have to be spent. What effect does this pressure wind up having on most of the movies we hear about? See the next chapter.

***

Writing around the time of the release of Star Wars, Episode I — The Phantom Menace, I’ve encountered more acknowledgment than usual in the press that the will of the audience and the success of a movie at the box office aren’t necessarily interchangeable. J. Hoberman’s review in the Village Voice, for example, spells out some of the reasons why:

However anticlimactic, The Phantom Menace is not only critic‐proof but audience-‐resistant as well. The movie has already made its money back ten times over through Pepsi’s just launched merchandising blitz alone, and thanks to Lucas’s pressure on theatrical exhibitors to guarantee lengthy exclusive runs (and the decision by rival distributors to cede him the rest of the spring), it would take the consumer equivalent of the Russian Revolution to keep The Phantom Menace from ruling the box office for weeks. (3)

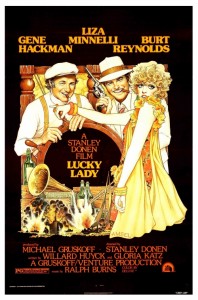

What’s new about The Phantom Menace is not so much the business methodology as the size of the apparent discrepancy this creates between what an audience wants and what it gets. Back in the mid-seventies, when I was working as assistant editor on Monthly Film Bulletin at the British Film Institute in London, I can recall seeing and reviewing one of the worst big-budget messes I’ve ever encountered in a lifetime of moviegoing — a caper movie about liquor smugglers in 1930 dodging the U.S. Coast Guard in San Diego and living it up in Tijuana. Here’s an excerpt from my review to give you some idea of what was involved:

With an outsized budget estimated variously at $12,600,000 (Variety) and £10,000,000 (Daily Mirror), three box-office favorites [Gene Hackman, Liza Minnelli, Burt Reynolds], and a script deliberately written, according to co-author Gloria Katz, as “the most commercial thing we could think up,” Lucky Lady is both conspicuously overproduced and undernourished. The presence of Stanley Donen [as director] seems to count for little in a project that might more logically have been entrusted to a computer. All it has to express, quite simply, are its deliberations: to combine as many saleable features as can be packed on a screen within the space of two hours. A little of everything is thus tossed into the mixture; and a great deal of nothing emerges out of the isolation and autonomy of the assorted elements. For Cabaret-like nostalgia, [cinematographer] Geoffrey Unsworth creates a hazy milk-of‐magnesia look with a dull sheen that obscures the details of the expensive sets and sea battles, both of which seem to derive from other models. As the leading lady, Liza Minnelli is dressed in a fright wig worthy of a nightmare dreamed by Robert Aldrich, given two unmemorable songs to sing, and encouraged or allowed to deliver each comic line (sample: “It’s so quiet you can hear a fish fart”) as if she were explaining it to a child of four, crushing gags like so many acorns in her wake. . . . It is harder to guess at a strategy behind the tinny soundtrack — where all the voices seem to occupy the same disembodied plane — unless one cites a box‐office precedent like Deep Throat or The Night Porter. . . . If, however, [the film] had concluded with the entire fleet of battling ships and all the characters consumed by one enormous tidal wave, thereby assimilating the disaster film and the science fiction epic into its strategies, it might have broadened its horizons far enough to encompass a few moments of old-fashioned entertainment. (4)

Nearly a quarter of a century has passed since then, and I have yet to encounter a single individual anywhere in my travels who admits to finding Lucky Lady halfway bearable, much less enjoyable. Yet only a year after its release, in Variety’s annual list of the “two hundred top moneymaking films of all time” (i.e., in movie‐industry hyperbole, up until early 1977), it wound up in the one hundred and thirty‐ninth place, having somehow grossed $12,107,000 in rentals — or about half a million less than its cost.

A veritable miracle, one might say. How could this have happened? It was easy. Given the stars and budget, Twentieth Century‐Fox demanded in advance that Lucky Lady be kept in theaters for extended runs if those theaters wanted to book it at all — a bargaining chip quite similar to George Lucas’s demand to exhibitors wanting to show The Phantom Menace, incidentally handled by the same studio. This meant that for long periods of time, in small towns across America, Lucky Lady was often the only movie playing, even if every one in town who’d already seen it hated it. So if you wanted to see a movie — any movie, for any reason — you saw Lucky Lady, regardless of what your friends said. It’s a bit like the orange juice and liquid soap jokes cited in the Introduction: for years after its release, Fox executives could confidently claim that Lucky Lady was exactly what the American public wanted, because that’s what they went to, in droves.