From the March 19, 2004 issue of the Chicago Reader. — J.R.

Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Michel Gondry

Written by Charlie Kaufman, Gondry, and Pierre Bismuth

With Jim Carrey, Kate Winslet, Elijah Wood, Mark Ruffalo, Kirsten Dunst, and Tom Wilkinson.

How happy is the blameless vestal’s lot!

The world forgetting, by the world forgot.

Eternal sunshine of the spotless mind!

Each pray’r accepted, and each wish resign’d;

Labour and rest, that equal periods keep;

“Obedient slumbers that can wake and weep;”

Desires compos’d, affections ever ev’n,

Tears that delight, and sighs that waft to Heav’n.

–Alexander Pope, “Eloisa to Abelard” (1717)

Only once in a blue moon does a screenwriter who isn’t a director become known as an auteur. Plenty of distinctive movie writers have reputations as actors or as actor-directors, starting with such giants as D.W. Griffith, Charlie Chaplin, and Erich von Stroheim, but they’re rarely celebrated for their writing. You have to go back to Robert Towne, who’s done only a little directing, and Paddy Chayefsky, who never did anything but write and produce, to find auteurs known mainly as writers.

A Chayefsky movie isn’t hard to identify, but I think it’s safe to say that these days a Charlie Kaufman movie is even more recognizable. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (May 14, 2004). This is probably my favorite Maddin feature to date. — J.R.

Mannerist film antiquarian Guy Maddin takes a bold step forward with this 2003 feature, a comic/melodramatic musical enhanced by his flair for expressionist studio shooting (in grainy black and white, with selected scenes in two-strip Technicolor). The project originated as a script by novelist Kazuo Ishiguro; revising extensively, Maddin and George Toles, his usual collaborator, turn it into an allegory about Canada’s colonial relationship with the U.S. In the depths of the Depression, a Winnipeg beer baroness (Isabella Rossellini) launches an international contest to come up with the saddest music in the world. Competing for the U.S. is her former lover (Mark McKinney), a brassy Broadway producer; for Serbia the producer’s older brother (Ross McMillan), who grieves for his dead son and vanished amnesiac wife (Maria de Madeiros); and for Canada both men’s father (David Fox), a surgeon who’s drunkenly amputated Rossellini’s legs. Not to be missed. 99 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

Below is my Foreword to The Medieval Hero on Screen: Representations from Beowulf to Buffy (McFarland, 2004), a collection edited by Martha W. Driver and Sid Ray, minus a few editorial tweaks and abridgements. — J.R.

It’s a curious fact, at least to me, that I’m writing a forword to this book, even a short one. I’m neither a medievalist nor a historian; I haven’t seen many of the films discussed, and, perhaps because I spend much of my time reviewing films for a weekly newspaper, the Chicago Reader, I have seen but have mainly forgotten some of the others. As a professional film critic who occasionally gets invited to speak and teach at college campuses, I have the benefit of both close and long-range views of film history, and try to create some two-way traffic between these positions in my writing.

It has always been a handicap for film scholars that one can’t necessarily count on all the important works being widely accessible or even widely known. In the essays that follow, some of my favorite films with medieval themes and settings have only been briefly touched upon —- I’m thinking especially of Carl Dreyer’s The Passion of Joan of Arc and Eric Rohmer’s Perceval -— while others, including Fritz Lang’s magnificent two-part, five-hour Die Nibelungen (1924), and Les visiteurs du soir (1942), a haunting fantasy written by Jacques Prévert and Pierre Laroche and directed by Marcel Carné during the French Occupation, are not mentioned. Read more

This appeared in the May 14, 2004 issue of the Chicago Reader, and occasioned one of the few thank-you notes I’ve received from a filmmaker for a review. I hope both Guy Maddin and those reading this will forgive me for immodestly reproducing his email: “Dear Jonathan: I usually try to avoid setting precedents that violate what should be a no-fly zone between critics and filmmakers, but I must say that your review of Saddest Music left me feeling understood at last!!! What a feeling. Thank you for supplying this euphoria. You also win bonus points for the Laura Riding discovery — I always liked her characters’ names. George Toles, who is terrified of reading reviews, will be thrilled to see his unsung name given its proper due. Not only that, you disabled Anthony Lane’s stinkbombs. A million thanks, Jonathan!! Warmest, Guy” — J.R.

The Saddest Music in the World

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Guy Maddin

Written by George Toles, Maddin, and Kazuo Ishiguro

With Mark McKinney, Isabella Rossellini, Maria de Medeiros,

David Fox, and Ross McMillan.

To Guy Maddin, every contemporary story that feels true is at bottom an amnesia story. — screenwriter George Toles

When all the archetypes burst out shamelessly, we plumb Homeric profundity. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (January 16, 2004). — J.R.

Treated as a debacle upon release, partially as payback for producer-star Warren Beatty’s high-handed treatment of the press, this Elaine May comedy was the most underappreciated commercial movie of 1987. It may not be quite as good as May’s previous features, but it’s still a very funny work by one of this country’s greatest comic talents. Beatty and Dustin Hoffman, both cast against type, play inept songwriters who score a club date in North Africa and accidentally get caught up in various international intrigues. Misleadingly pegged as an imitation Road to Morocco, the film is better read as a light comic variation on May’s masterpiece Mikey and Nicky as well as a send-up of American idiocy in the Third World. Among the highlights: Charles Grodin’s impersonation of a CIA operative, a blind camel, Isabelle Adjani, Jack Weston, Vittorio Storaro’s cinematography, and a delightful series of deliberately awful songs, most of them by Paul Williams. 107 min. A 35-millimeter print will be shown. Univ. of Chicago Doc Films.

Read more

Read more

From the April 23, 2004 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

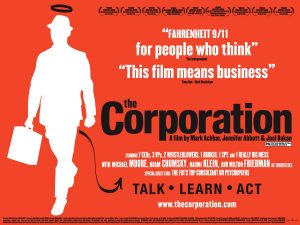

Absorbing and instructive, this 2003 Canadian documentary tackles no less a subject than the geopolitical impact of the corporation, forcing us to reexamine an institution that may regulate our lives more than any other. Directors Mark Achbar (Manufacturing Consent) and Jennifer Abbott and writer Joel Bakan cogently summarize the history of the chartered corporation, showing how it accumulated the legal privileges of a person even as it shed the responsibilities. This conceit allows the filmmakers to catalog all manner of corporate malfeasance as they argue, wittily and persuasively, that corporations are clinically psychotic. The talking heads include not only political commentators like Noam Chomsky, Milton Friedman, Naomi Klein, Michael Moore, and Howard Zinn, but CEOs such as Ray Anderson, Sam Gibara, Robert Keyes, Jonathon Ressler, and Clay Timon, whose insights vary enormously. This runs 145 minutes, but it’s so packed with ideas I wasn’t bored for a second. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (February 27, 2004). — J.R.

A newly appointed homicide detective in San Francisco (Ashley Judd) tracks a serial killer whose victims are all men she has slept with. Director Philip Kaufman, who usually writes his own scripts, works with a cliche-ridden screenplay by Sarah Thorp, and his personal touches mainly seem to consist of selecting fashionable North Beach bars as locations. His usual flair for erotic detail largely deserts him here, and this thriller seems most interested in lingering over battered and bloodied male faces. Samuel L. Jackson and Andy Garcia costar. R, 97 min.

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (April 2, 2004). This wonderful documentary, incidentally, is now available on the Criterion DVD of Pickpocket. One of its most fascinating paradoxes for me is that Mangolte, a friend, isn’t a religious person, but this documentary strikes me as profoundly spiritual; Lasalle’s home is even treated as a sacred shrine. — J.R.

Les modèles de “Pickpocket”

***

Directed and written by Babette Mangolte

With Pierre Leymarie, Marika Green, and Martin Lasalle.

Not until he was in his late 90s did Robert Bresson get the recognition he deserved. He died in 1999 at the age of 98, living long enough to see his work affirmed by a retrospective the Toronto Cinematheque’s James Quandt organized that traveled around the world to full houses.

For years mainstream critics regarded Bresson as esoteric, pretentious, even something of a joke. “The chief fault is that the hero is a vacancy, not a character,” wrote Stanley Kauffmann in one of the more sympathetic reviews of Bresson’s 1959 Pickpocket, a free adaptation of Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment. “Martin Lasalle, who plays the part, has a bony, sensitive face, but no deader pan has crossed the screen since Buster Keaton. The besetting fallacy of modern French films and novels is the belief that nullity equals malaise and/or profundity.” Read more

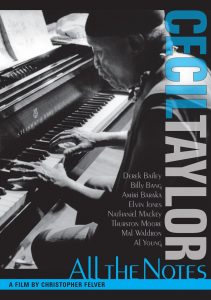

From the May 14, 2004 Chicago Reader. P.S. I once went to hear Cecil Taylor at a San Francisco club in the 1980s with Nathaniel Mackey (as well as Trinh T. Minh-ha and the late Bell Hooks).- J. R.

Any musician of Cecil Taylor’s caliber deserves sustained attention, but the jazz great doesn’t get it in this rambling assortment of alternating sound and music bites. Taylor is a nonstop pontificator of varying interest as well as a brilliant and virtuosic avant-garde pianist, but director Christopher Felver treats his music and his remarks as equally relevant, cutting between them — or away to still photographs — as if determined not to focus too long on any one thing. On piano Taylor employs an idiosyncratic technique, sometimes using his elbows as well as his fingers, and I’d hoped the camera angles would reveal this; apart from a brief shot behind the final credits, however, Felver shows almost everything except the keyboard. At least the other talking heads have things to say, including Elvin Jones, Amiri Baraka, Nathaniel Mackey, and Al Young. 71 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From The Guardian, August 27, 2004, where this appeared under the title “Independence Day”. — J.R.

It’s an enduring and endearing paradox of Jim Jarmusch’s art as a writer-director that even though it may initially come across as a triumph of style over content, it arguably turns out to be a victory of content over style. The humanism of this mannerist winds up counting for more than all his stylistic tics, thus implying that his manner may simply be the shortest distance between two points.

Maybe it’s the ultimate paradox of minimalism: the less your work does and is, the more these things matter. In Jarmusch’s case, this partially means that the very notions of hipness and independence that originally defined his stylish filmmaking in the 80s — with Permanent Vacation (1980), Stranger Than Paradise (1984) Down by Law (1986), and Mystery Train (1989) — started working against his public profile in the 90s, especially once being outside the mainstream started being regarded with greater suspicion.

Furthermore, around the time of Jarmusch’s Night on Earth (1992), released the same year as Reservoir Dogs, hipness and independence as values within American culture had both become somewhat muddled and coarsened in the process of becoming mainstreamed. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (May 22, 1992). — J.R.

THE 4TH ANIMATION CELEBRATION: THE MOVIE

*** (A must-see)

Finding out what’s happening in the world these days is no easy matter. Turn to a newspaper and we may learn what American business wants to know — or thinks it wants to know — but not much else; check out what’s on TV and chances are that the state of the world will get less attention than the current Hollywood releases. Even when there is expanded coverage we often can’t be sure that the journalists understand what they’re reporting or that what they’re saying encompasses all that they understand.

I suppose this has always been true to some extent, and maybe it only seems worse nowadays because we no longer have newsreels. Recently some fascinating “March of Time” shorts have come out on video — newsreel “essays” produced by Time-Life and released in movie theaters by Twentieth Century-Fox in the 30s, 40s, and 50s. What seems most quaint and touching about them is how easily people (both famous and ordinary) were induced by the camera to play fictional versions of themselves that they and everyone else were persuaded to think of as real. Read more

From The Movie, Chapter 33 (1980). -– J.R.

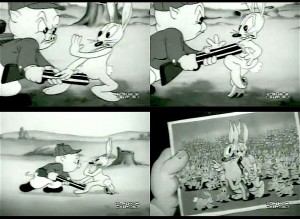

It was in 1940 that a brisk, buck-toothed city rabbit first sank teeth into carrot. briefly paused, gazed with indifferent aplomb at a lisping country rabbit-hunter with a shotgun and coolly inquired: ‘What’s up, Doc?’ This official debut of Bugs Bunny occurred at the beginning of A Wild Hare, one of nine cartoons that were supervised that year by Fred (known as ‘Tex’) Avery, a brilliant animator from Dallas who was working for Warner Brothers. The cartoon won an Academy Award nomination and the durable comedy team of Bugs Bunny and Elmer Fudd promptly went into business.

‘That darn wabbit!’

Bugs Bunny, first seen in Porky’s Hare Hunt (1938), had a complicated cross-bred genealogy. Remembering the ‘What’s up, Doc?’ expression from his high-school days in Texas, Avery had decided to place it in the mouth of a sharp Brooklynese rabbit who knew everything. Avery later recalled in an interview:

‘So when we hit on the rabbit we decided he was going to be a smart-aleck rabbit, but casual about it, and I think the opening line in the first one was, “Eh, what’s up, Doc?,’ And gee, it floored ’em! Read more

From the November 1, 1995 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

Simultaneously quite watchable and passionless, Martin Scorsese’s three-hour dissection of power in Las Vegas (1995), set principally in the 70s, sometimes comes across like an anthology of his previous collaborations with Robert De Niro — above all GoodFellas, though here the characters are high rollers to begin with. By far the most interesting star performance is by Sharon Stone as a classy hooker destroyed by her marriage to a bookie (De Niro, in the least interesting star performance) selected by the midwest mob to run four casinos. There’s an interesting expositional side to the film, with De Niro and Joe Pesci’s characters both serving as interactive narrators, but the film never becomes very involving as drama, and the appropriation of Georges Delerue’s theme from Godard’s Contempt is the tackiest hommage since the use of Singin’ in the Rain in A Clockwork Orange. With James Woods, Don Rickles, Alan King, Kevin Pollak, and L.Q. Jones. (JR)

Read more

From Sight and Sound (Autumn 1974). — J.R.

The first and perhaps the final question to be asked about Peter Bogdanovich’s adaptation of Henry James’ novella is simply why he chose to embark on it. A revealing interview with the director by Jan Dawson which appeared in Sight and Sound last winter affirms that he is anything but a Jamesophile (‘The social aspects of it don’t really concern me’), and one would imagine that taking up an admittedly minor — if commercially celebrated — work by the grey eminence would at least be dictated by an interest in the tale as ‘raw material’, an expedient for arriving at his own creation. But the confounding thing about his Daisy Miller is that it comes across as neither fish nor fowl: too indifferent to Jamesian nuance to qualify as appreciation, too faithful (in terms of the overall plotting and dialogue in Frederic Raphael ‘s script) to gain credence as an attack on the original — and yet too amorphous and uncertain in its own terms to register as an independent and autonomous work.

One suspects that the attractions of the project were the mythic elements: American innocence and charm in confrontation with European decadence. Read more

This was written for the Writers Guild magazine Written By; it ran in their August 1997 issue and was later reprinted in my collection Essential Cinema.

My comparison of May with Erich von Stroheim, which may sound frivolous, is actually something I take very seriously. Both filmmakers are mainstream figures with the temperaments of avant-garde artists; Orson Welles’ description of Stroheim’s style as “Jewish baroque” also fits May’s quite well; and perhaps most significantly of all, both of these highly obsessional writer-director-performers create films populated almost exclusively by monsters, yet characters whom their creators clearly love. In this latter respect, May might even be considered more radical than Stroheim because one can’t cite a single villain in her four features — unlike, say, Schani the butcher (Matthew Betz) in Stroheim’s The Wedding March. Furthermore, for me, the two greatest Stroheim films, Foolish Wives and Greed, are echoed in many respects by The Heartbreak Kid and Mikey and Nicky, the two best films of May.

On the evening of June 27, 2010, in Bologna, Italy, I had the rare, unexpected, and delightful privilege of spending a couple of hours with May. It was a friendly conversation over dinner rather than any sort of interview, but she did tell me in passing a few things about her life and work that I’ve added to this piece as footnotes. Read more