Chapter Seven of my book Movie Wars: How Hollywood and the Media Limit What Films We Can See (Chicago: A Cappella Books, 2000). The cover below is that of the U.K. edition published by the Wallflower Press. Because of the length of this chapter, I’m posting it in two parts. — J.R.

TRANSATLANTIC REALITY AVOIDANCE: A REPORT FROM THE FRONT (MAY 1999)

“ ‘I think, therefore I am,’ ” reads the opening epigraph of The Thirteenth Floor, the fourth virtual‐reality thriller I saw in Chicago in as many weeks in the spring of 1999, followed by the quotation’s source, “Descartes (1596–1650).” It’s an especially pompous beginning for a movie whose characters scarcely think, much less exist, but not an unexpected one given the metaphysical claims and pronouncements that usually inform these thrillers.

If any thought at all can be deemed the source of these pictures cropping up one after the other — with the exception of David Cronenberg’s eXistenZ, a film with a lot more than generic commercial kicks on its mind — this might be an especially low estimation of what an audience is looking for at the movies. The assumed desire might be expressed in infantile and emotional terms: “I don’t like the world, take it away.” In other words, the virtual-reality thriller seems to solve the puzzle of how to address an audience assumed to be interested only in escaping without reminding them of what they’re supposed to be escaping from. It smacks of significance by indulging in glib self-referential hints that movies are just a form of dreaming anyway, implies that anything that suggests the real world is — or might as well be — a hallucination, and is usually “thoughtful” enough to include gobs of violence on the assumption that even if the world is no longer desirable, kicking ass for any reason at all is. And in the cases of The Matrix and The Thirteenth Floor, the two studio blockbusters in the batch (the other two being the Spanish movie Open Your Eyes and eXistenZ), a worshipful attitude towards digital technology appears to be the only factor that justifies the conceits about alternative realities in terms of science fiction rather than a less prestigious and more hybrid form like science fantasy. As the press book for The Thirteenth Floor eagerly puts it, “Over two thousand years ago, Plato postulated that the ‘real’ world exists only in our imagination. The technology of modern society has begun to prove Plato’s point.” Thanks a lot, modern society; tough luck, Kosovo Albanian and Serb civilians.

The only point at which I differ from Jonathan Schell’s remarks about virtual reality at the beginning of this chapter (“In our variant of self‐deception, pleasure plays the role that terror plays under totalitarianism”) is his suggestion that “the prime need it serves is probably not political at all,” which my European‐trained bias is tempted to label Famous Last Words. This is because avoidance of politics qualifies as a political position just like any other, and the desire to avoid politics in American life, however primal, stems from political suppositions, often unacknowledged as such. Accepting and/or submitting to the status quo is commonly regarded as a “neutral” position, but the twentieth century has already amply taught us that neutrality in certain contexts amounts to defeat or alienation at best, complicity at worst.

At the beginning of most movies, including quite a few bad ones, there’s a period of grace when exciting possibilities still hover. The same feeling of both mystery and potentiality presides at the beginning of film festivals — the titles, directors, actors, countries, and catalogue descriptions portend all sorts of things. Disappointment generally follows when the promises aren’t kept and the anticipatory dreams go unfulfilled, except for those interesting occasions when expectations get revised on the spot (or a few days afterward) and unforeseen pleasures start to emerge. More often, the exciting possibilities gradually become narrowed down into familiar, shopworn routines—the kind that our experts inform us are the only sure-‐fire things that sell (except for when they don’t).

So I have to admit that The Thirteenth Floor kept me hoping for the first half-hour or so, before it turned into another virtual-reality boondoggle. The press screening was held the morning after the prizes at the 1999 Cannes film festival were announced, and because this was the first year since 1993 that I didn’t attend at least part of that event, I still had months or in some cases years to wait before the movies there that interested me the most had even a chance to disappoint me. You might say that this is my own virtual-reality game, playable in different ways in terms of both The Thirteenth Floor and the Cannes festival I didn’t attend, though the difference between waiting half an hour and waiting several months is not to be sneezed at: in the latter case, for instance, I had to worry more about all the misinformation that was likely to gum up my expectations in the interim.

I don’t mean to suggest that virtual‐reality thrillers are the only form of virtual reality in our midst. All four that appeared in the space of a month roughly coincided with the Cannes festival, including its preliminaries and immediate aftermath, and the American coverage of that event seemed boxed in by a comparable set of assumptions. The ruling philosophy behind most of this coverage seemed to be, why should we be interested in new films from all over the world unless it’s to ratify what we already know? Why, for instance, didn’t they show Star Wars, Episode I—The Phantom Menace? Why weren’t there any more Hollywood blockbusters? (“Cannes picks dour pix, snubs H’w’d,” trumpeted a Variety headline before the festival even started.) And, most important of all, how happy or unhappy is or was Harvey Weinstein, cochairman of Miramax, about the festival as a whole?

The happiness or unhappiness of Harvey has become the main theme of North American film festival coverage in recent years; it’s equally prominent in reports from Sundance, and whenever Oscar night rolls around you can bet that cameras will be poised to discover how he’s feeling at various selected moments — especially those that confirm whether the Oscars he’s worked and paid for get delivered or not. At Cannes, where the focus is supposedly on hundreds of movies rather than a handful of box‐office favorites, and supposedly on artistic merit rather than in-house industry popularity, the American press gets indignant if Oscar‐night results aren’t approximated, Harvey’s beam of approval included. This year, the attitude appeared to be, “I don’t like the world, take it away” — a complaint seemingly addressed to Harvey, who presumably knows how to take it away and even where to take it.

Unfortunately for the American press, this wasn’t the year when Harvey could take charge. He seemed pretty unhappy when the Cannes prizes were being announced — most of them, incidentally, to filmmakers I admire a good deal more than most of the pets in his stable—and his fans in the press seemed incensed that his tastes weren’t being honored. But since Harvey’s displeasure invariably bolsters my faith in the future of world cinema, Cannes’s 1999 winners seemed to be a pretty invigorating bunch.

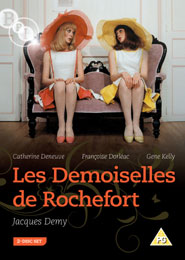

The argument is that Weinstein dominates the stateside distribution of specialized movies — he’s supposed to be the Nero or Caligula with the thumbs up or thumbs down perogative — but how he manages to maintain this dominance is discussed less often. Critics who call him the distributor most responsible for enabling us to see foreign films aren’t doing simple arithmetic. Because Miramax picks up over twice as many films as it releases — keeping most of its unreleased pictures in perpetual limbo, shaping and recutting most of its favorites, and marginalizing most of the others so that only a handful of people ever get to see them — there’s statistically less chance of the public ever having access to a movie if Miramax acquires it. (Why are all of Abbas Kiarostami’s recent features except for Through the Olive Trees available for rental on video? Guess which one Miramax “distributes.” And why did most Americans never get a chance to see either the color version of Jour de fête or the restoration of The Young Girls of Rochefort? Guess again. It’s been speculated that one reason why Miramax picks up so many films is in order to prevent other distributors from acquiring them; if this is true, then I guess we’re supposed to conclude that Miramax’s profit motive is more important than the desire of many people to see these and other films that are kept out of reach.) Yet if you follow the drift of The New York Times, the Chicago Sun‐Times, the Chicago Tribune, Variety, and comparable publications, Harvey’s disposition at any given moment appears to be a useful shorthand for the overall health and direction of world cinema. It’s certainly a lot easier to track than what a bunch of difficult foreign filmmakers have to say about the state of the world and what an unpredictable international jury — headed in 1999, as it happens, by David Cronenberg — decides is most valuable. So why not conclude that Harvey’s mood is more interesting and important as well?

On the other hand, if it’s a question of selling a feel‐good Holocaust comedy like Life Is Beautiful, it’s hard to deny that Miramax conquers markets that true independent distributors are unable to penetrate. Visiting my home town recently, I discovered that Life Is Beautiful was playing even in Florence, Alabama; it may have been the first time a subtitled film had shown there theatrically in four decades, ever since my family’s former chain of theaters became reluctantly independent.

Seeing a subtitled feel-good Holocaust movie may be better than not seeing any subtitled movies at all — just as seeing a virtual‐reality thriller may be better than seeing no SF thrillers of any kind. A bird in the hand is worth two in the bush, and if the bushwhackers at Cannes want to send home something ready for the microwave, they may feel they have to depend on a Harveyburger rather than on anything more exotic. But if that’s the case, they have an opinion of their public that’s not dissimilar from that of the people churning out virtual‐reality thrillers. What’s happening in the world outside of virtual reality is a lot more complicated than what’s happening inside, and if the inside is all we’re equipped to deal with, then we can’t be very well equipped.

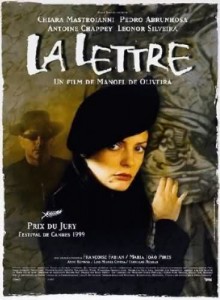

Certainly not equipped to cope with the film that won the jury prize at Cannes, Manoel De Oliveira’s The Letter — his adaptation of the first great short novel in French, Madame de Lafayette’s La princesse de Clèves (not Madam de Cleeves, as the Tribune had it, or La princesse de Cleeves, as BRAVO’s Cannes coverage pronounced it). I haven’t liked all of De Oliveira’s films — even if he’s incontestably the greatest of all Portuguese filmmakers as well as the oldest filmmaker anywhere currently at work, and the only one left who started out in silent cinema. His last feature, Inquiètude, placed first on my 1998 ten‐best list, but it’s theoretically possible, if I’d attended Cannes in 1999, that I might have concluded, along with Roger Ebert’s colleagues (as reported in one of his Cannes dispatches), that The Letter was “the second or third worst film in the festival.” (Could it have been those same esteemed colleagues who noisily walked out at Cannes during the exquisite final shots of Terence Davies’s The Neon Bible, or who chastised Jim Jarmusch for not letting Harvey recut Dead Man?) I also might have concluded that a jury comprising, among others, Cronenberg, Holly Hunter, George Miller, and André Téchiné might have something to teach me, so their verdicts might have at least piqued my curiosity.

And what about the other disputed Cannes prizewinners? The Palme d’Or went to Rosetta by Luc and Jean‐Pierre Dardenne, the Belgian brothers who made La promesse; the grand jury prize, best actor, and half of the best actress award went to L’humanité by Bruno Dumont, the French filmmaker who made La vie de Jésus; the other half of the best actress award went to Emilie Dequenne in Rosetta (apparently increasing the outrage was the fact that all three acting awards went to nonprofessionals); best screenplay went to the Russian-German coproduction Moloch by Russian filmmaker Aleksandr Sokurov, another major artist generally shunned or else jeered at by the Miramax hounds. Relatively undisputed by the American press was the best director prize to Pedro Almodovar for his Spanish crowd‐pleaser All About My Mother and best set design prize to Chen Kaige’s The Emperor and the Assassin. (Chen’s previous film, the initially hypnotic Autumn Moon, was reedited into indigestible chopped liver by Harvey, which I assume is what makes him acceptable to large portions of the American press.)

Bearing in mind that some Cannes awards are compromises rather than unanimous choices, there’s still a discernible profile that emerges from the dominance of films by gifted regionalists that is clarified by some remarks made by Austrian critic Alexander Horwath a couple of years ago, to which I’ve added a couple of tentative amplifications:

In the framework of film‐cultural globalization two fake alternatives have evolved: the Miramax idea of U.S. “indies” and the reduction of European art cinema to a few “masters” who can transcend all national borders and dance in all markets (Kieslowski and Zhang Yimou might be two good examples [to which one might add Almodovar and Chen]). I am much more interested in filmmakers who speak in concrete words and voices, from a concrete place, about concrete places and characters. I like the image of the brothers Dardenne . . . standing somewhere in the middle of industrial Belgium, looking around and saying, “All these landscapes make up our language” [which also might be said of Dumont standing somewhere in rural France]. Next to the filmmakers we’ve often discussed (like Ferrara, Assayas, Egoyan, Wong Kar-wai, et al.) there are many more if lesser known examples of such a kind of cinema. Their dialects are much too specific to fit into the global commerce of goods — in Austria: Wolfgang Murnberger (today), John Cook (in the 1970s); in Germany, Michael Klier, Helge Schneider. Or in Kazakhstan: Darezhan Omirbaev. And even in Hollywood: Albert Brooks. (1)

___________________________________________________

[1] “Movie Mutations,” by Jonathan Rosenbaum, Adrian Martin, Kent Jones, Alexander Horwath, Nicole Brenez, and Raymond Bellour, in Film Quarterly, vol. 52, no. 1, fall 1998, p. 46. Note: this is a condensed English version of an article roughly twice as long that first appeared in French in Trafic no. 24, 1997, and has also appeared in its full version in Dutch (Skrien nos. 221–225, 1998), German (Meteor nos. 12 & 13, 1998), and Italian (Close Up no. 4, 1998).

The fact that I recognize only the two last names in Horwath’s final list gives me further cause for hope, but from the looks of things, the same evocation of untapped pleasures beyond the Miramax radar is more likely to elicit groans and consternation from the American press. The tension between art and commerce at Cannes has always been fierce, but in past years a certain amount of strained coexistence has always been possible. I expect it’s still that way, but judging from all the American reports I’ve encountered from Cannes this year, it sounds like the art contingent has been reduced to the size of a pesky gnat. (Here’s Variety’s way of putting it: “If the Rosetta award was a jolt, things really got out of hand with L’humanité, a two-and-a-half-hour account of the slowest murder investigation ever filmed that provoked considerable critical derision from everyone except, perhaps, certain French critics.”) The fact that this year the gnat bit Harvey’s ass is apparently what’s causing all the fuss.

POSTSCRIPT: HARVEY BITES BACK

Three days after I submitted the above article to the Chicago Reader and five days before it was published, Janet Maslin eliminated my niggling fears that I might have exaggerated the national press’s obsession with Harvey Weinstein at Cannes. In her Sunday “wrap-up” piece about the festival in The New York Times (May 30, 1999), Maslin went beyond my previous examples and made Weinstein’s distress the only major event deserving extended coverage. After four short and dutiful paragraphs devoted to the prizes given to “two intense, painful French‐language films dealing with hard lives in lonely surroundings” (i.e., Rosetta and L’humanité), she devoted the following eight paragraphs to what clearly mattered most to her about the festival (I’ve italicized three of her sentences in order to make points about them later):

In any case, this was the year that Harvey Weinstein of Miramax declared war. Weinstein has long been galled by this event’s elitism and its predilection for dull, irrelevant films and he thinks it’s time for a change. “There’s something wrong with Cannes, and it needs to be fixed,” he said angrily by telephone from the closing night party. “The luster of the festival is completely submerged. It’s losing its place in film history. It has the potential to be so much more than it is now, the potential to be so much more serious and less political. I’ve reached the frustration point, and I’m not scared to say so any more.”

Of course Weinstein could be accused of sour grapes. Miramax’s version of Oscar Wilde’s Ideal Husband was this year’s closing night film and Kevin Smith’s Dogma was an out-of‐competition hot potato. (Miramax bought back Dogma to shield Disney, its parent company, from possible protests against the film’s views on Catholicism.)

But otherwise, the usually unstoppable Miramax team was practically AWOL. Then again, the big American studios were also missing with the notable exception of Disney, which was attached to films by David Lynch, Tim Robbins and Spike Lee.

“I feel a very sentimental attachment to Cannes, but I’m tired of begging,” said Weinstein, who had no luck getting Dogma into the main competition, though there was room for a two and a half hour soap opera (Our Happy Lives) about a group of star-crossed French characters. “I’m tired of fighting for obvious choices.” (Among Miramax’s previous rejects for Cannes’ main competition are My Left Foot and The Crying Game.)

So he spent much of this year’s festival stirring up producers, directors and financiers of his acquaintance. Maybe they will be able to offset the doldrums that are especially extreme. When the Variety critic Todd McCarthy fired off a salvo against overlong films of no interest to anyone but their creators, his column was more popular than most of the movies in town. And if nothing changes? “Then I won’t come,” Weinstein said.

If that sounds like a no-prisoner stance, it’s also an indication of what an extreme sport Cannes can be from a business standpoint. That’s what it amounts to for the small club of distributors who dominate American art-house fare.

This was followed by seven more paragraphs –- the first two devoted to which American distributors other than Miramax picked up half a dozen films for distribution, clearly the subject that interested her least in the article, and the last five devoted to the gear employed by those distributors in Cannes — e.g., a bicycle for Sony Classics’ Tom Bernard, hiking boots for Fine Line Features’ Mark Ordesky — which captured substantially more of her attention and apparent interest.

I suspect an entire book could be written about the meanings of both “film history” and “political” as Weinstein understands those terms, but it’s not a book I would ever care to write or even research. In order to contemplate the first, I suspect I’d have to ignore a good 95 per cent of the films I care about the most and concentrate on items like The Crying Game and My Left Foot that made Harvey a lot of money. And in order to write about “political” in contradistinction to “serious,” an American yahoo specialty, I’d have to ignore everything I learned about politics over nearly eight years of living in Paris and London — an education that started with the premise that politics were involved with everything that improved the quality of one’s life, society, and environment (2), not merely with the results of an election or a festival jury’s vote that improved one distributor’s bank account.

Anyone who’s ever attended the Cannes festival knows that one can carve about as many publics as one wishes out of the hordes of people attending. (After all, Cannes is only the world of film in miniature, and as Oscar Wilde once aptly noted, “There are as many publics as there are personalities.”) So I’m not unduly surprised when Maslin reports that Todd McCarthy’s own attack on the 1999 Cannes selection “was more popular than most of the movies in town” — even if she’s the only one I’ve encountered so far who has voiced that sentiment or anything close to it — because all critics, myself included, tend to find what they go looking for. But I can’t help but conclude that she’s living in a very different universe from mine. Even Weinstein, I presume, might have preferred his own two films at the festival to McCarthy’s column, though here I’m strictly second-guessing this Dickensian character.

_____________________________________________________

[2] A perfect illustration of this premise is Rosetta itself, especially if one considers that the film inspired a new Belgian law known as “Plan Rosetta,” passed on November 12, 1999, prohibiting employers from paying teenage workers less than the minimum wage. To the best of my knowledge, this fact went unreported in the American press apart from my own Chicago Reader review (January 14, 2000) — which isn’t surprising given the usual tendency to treat audiences like servants of Disney rather than citizens of the world. But judging by discussions I had with two separate Chicago audiences who saw the film, the film’s political, visceral, and emotional power registered loud and clear.

As a rule, Maslin during her visits to Cannes attended only the films in competition and a few high-profile special events, and often missed several of these (such as Taste of Cherry during the last year I attended Cannes as a critic). So what she described as “most of the movies in town” was an expedient fiction that suited her temperament and inclination to see as little of the range of what Cannes has to offer as she could manage to get away with. (Truthfully, no single human being could comment intelligently or even intelligibly on “most of the movies in town” when several dozen are screened daily.) It’s also evident that she had little desire to hang out with critics more interested and knowledgeable about movies than she was, because this might make her at least faintly aware that she might be missing something. (I’m ruling out some of the titles that interest me the most, like Jean- Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet’s Sicilia!, because I couldn’t imagine her sitting through them, but surely there were other, less demanding items she might have enjoyed.)

Most of my friends attend dozens of other screenings in the numerous other sections of the festival, and practically all of them reported back that the 1999 Cannes festival was full of interesting and exciting things to see, including several of the films in competition. None of them, I should add, showed any interest in what Harvey Weinstein had to say about these movies — unless this was related to whether American viewers would ever get to see them or not. (In most cases, it wasn’t.) Much more relevant to this issue was whether or not they might have been selected by the film festivals in New York, San Francisco, and Toronto, among many others.

As a postscript, it’s worth adding that David Cronenberg’s response to Harvey Weinstein has so far — to the best of my knowledge, judging by the reach of my computer’s search engines — appeared only in French, a significant fact in itself. An interview with Cronenberg by Laurent Rigoulet appeared in the June 2, 1999 issue of Libération, entitled “Cronenberg contre-attaque.” Some of Cronenberg’s points — such as his insistence that his jury’s prizes aren’t supposed to be popularity contests — are similar to mine. (He also emphasizes that the jury found the films in competition exciting even when they were failures “because they attempted something,” and compared the experience favorably to the “depressing” experience of being sent videos of Oscar‐nominated films every year, “essentially a minifestival of American movies . . . where one sees the same strategy everywhere and feels pitifully grateful towards the minor film that tries to find a slightly different approach.”) But it’s only fair to note his claim that there were no conscious political or intellectual motives behind his jury’s decisions. (He also stressed that the decision to award two acting prizes to the nonprofessionals in L’humanité was based strictly on the quality of the performances, not on the biographies or filmographies of the actors.) Dismissing McCarthy’s attack in Variety as “pure Hollywood propaganda,” he adds (the translation is again mine), “You have to understand that Cannes has become an insult to the Americans. They find this festival marvelous and they want to make it their own. And since they haven’t succeeded in taking it over, they’ve begun to hate it. They say that the festival has lost its reason for existing, that it’s ‘irrelevant.’ That’s a wonderful word for the films we’ve chosen. What does it mean? I believe that’s the way Harvey Weinstein, the boss of Miramax, put it. I’d love for him to explain to me what makes Shakespeare in Love more relevant than Rosetta. What does it mean that a feel-good comedy set in Elizabethan England represents for him an artistic film whereas Rosetta lacks relevance?”

***

The apparent conviction of so many American “experts” in Cannes that foreign material is somehow contaminated unless it gets the Weinstein seal of approval (and the editing “polish” that usually goes with it) seems analogous to the blinkers that define what’s plausible in relation to class‐bound assumptions. We often tend to forget that what we call realism, from Emile Zola to David Denby, almost invariably derives from a class position. One very useful aspect of Denby’s film criticism, apart from the beautifully chiseled construction of his prose style, is the way it reliably and sometimes hilariously reflects middle‐class or upscale blindness to the world that everyone else inhabits. In his review of Eyes Wide Shut, for example, we discover in the course of his reality lessons that “a prostitute who picks up [the hero] and takes him home is patently too beautiful and too well educated to be working the pavements.” When I cited this remark to a friend, she replied, “I guess he’s not doing trade.” The only on-screen evidence of education I could spot was a sociology textbook and an Oscar Peterson CD; but clearly middle-class constructions of street hookers exclude such workaday possibilities, along with beauty. Woody Allen’s uncouth prostitutes and convicts must be more ideologically correct specimens, since they’re more apt to use terms like “dem” and “dose.” Maybe I’m jumping to conclusions in assuming that Denby has less trouble with these middle‐class fantasies of Allen’s — all seemingly derived from Warners crime pictures of the thirties — but he certainly wouldn’t be alone in this bias; Mia Sorvino actually won an Oscar for playing the cartoon hooker in Mighty Aphrodite. (Nobody accused her of being too beautiful for the part, but then again, she wasn’t working the streets.)

I could be wrong about this, but I suspect that at least part of what made so many American critics incensed by Kubrick’s unfashionable, posthumously released masterpiece was that it was shot overseas by an expatriate, even though it was set in New York. Perhaps because it starred Tom Cruise, carried the Warners logo, and was made by a filmmaker who spent roughly the first half of his life in the United States, people went expecting an “American” film of the nineties and got something else — an essentially nationless movie reflecting just about every decade in this century except the nineties, which transplanted a remarkable Arthur Schnitzler novella written in 1926 and set in pre-World War I Vienna into a mannerist English studio representation of New York City roughly a century later. (3) Certainly the film was American in some respects, but there were other, equally valid ways in which it might be regarded as English, Austrian, or, even better, as transnational or multinational — a category that we’ve so far learned to identify economically but not yet culturally or existentially.

_________________________________________________

[3] Some New York critics poignantly inquired how a movie about New York could get so many facts about the city wrong. But the notion that Kubrick’s film is “about” New York is absurd to begin with — apparently motivated by these critics’ desire to validate themselves as New Yorkers rather than to say anything meaningful about the movie. Nobody would think of claiming that Schnitzler’s story was “about” Vienna — its title is Traumnouvelle, not Viennanouvelle — so it hardly seems reasonable to assume that Kubrick would want to make a movie about a city he hadn’t visited at least since the early eighties. Similarly, the insistence of some of these critics that the film remains “unfinished” because Kubrick never completed the sound mixing not only contradicts the testimony of Kubrick’s widow, an artist herself, but suggests a curious double standard relative to their treatments of films such as Mr. Arkadin, which Orson Welles was unable to finish editing.

It’s worth stressing that a lot of what audiences today routinely regard as “American” isn’t — at least not in the way that such a term used to apply to studio releases. (This is the subject of the next chapter, and another pertinent cause of our everyday alienation regarding movies.) We’ve been trained to confuse labels with contents, and outmoded critical categories and reflexes with contemporary practices — which leads us to discuss videos as if they were movies and the tastes of producers and publicists as if they were the tastes of audiences. So it’s only natural that we should wind up considering multinational movies as American if enough American or “American” stars (Arnold Schwarzenegger would qualify) are featured. Never mind that the funding might be foreign, not to mention the director, writers, and/or crew; the whole thing is still supposed to be “ours” even if it belongs to Japanese or Arab investors. And maybe this misperception wouldn’t matter so much if we didn’t keep applying notions of — and assumptions about — national cinema to releases that confound such categories, so that what constitutes “an American movie” in the year 2000 often has scant relation to what was defined as such in 1950. As suggested earlier, this implies that our isolationism is historical as well as geographical — a condition of being lost in time as well as space.