From the Chicago Reader (September 5, 1997). — J.R.

Contempt

Rating **** Masterpiece

Directed and written by Jean-Luc Godard

With Brigitte Bardot, Michel Piccoli, Jack Palance, Fritz Lang, Giorgia Moll, and Godard.

Almost exactly 33 years ago, in October 1964, the critical reception of Jean-Luc Godard’s widest American release of his career and his most expensive picture to date was overwhelmingly negative. But now that Contempt, showing this week at the Music Box, is being rereleased as an art film — in a brand-new print that’s three minutes longer — the critical responses have been almost as overwhelmingly positive. It’s tempting to say in explanation that we’re more sophisticated in 1997 than we were in 1964 — that we’ve absorbed or at least caught up with some of Godard’s innovations — but I don’t think this adequately or even correctly accounts for the difference in critical response. Despite all the current reviews that treat Le mépris as if it were some form of serene classical art, it’s every bit as transgressive now as it was when it first appeared, and maybe more so. But because it’s being packaged as an art movie rather than a mainstream release — because Godard is a venerable master of 66 rather than an unruly upstart of 33 — we have different expectations.

I can remember how puzzled I was by this gorgeous film as an undergraduate. Though it was Godard’s sixth feature, it was only the third to be released in the United States, preceded by Breathless in 1961 and by Vivre sa vie in 1963. The first of these was a cheap American-style thriller in black and white, the second a cheap French-style art film in black and white; Contempt, in glorious Technicolor and ‘Scope, clearly didn’t belong to either category. A big international coproduction (starring Brigitte Bardot and Jack Palance) that even played in my hometown in Alabama, it virtually began with a scene in which Bardot was stretched out nude on a bed beside a fully clothed, then-unknown Michel Piccoli while they engaged in a curious romantic dialogue about how much he loved her various parts; a seemingly unmotivated use of red and blue filters punctuated the full-color shots. Coproduced by the vulgar American showman Joseph E. Levine — best known at the time for his distribution of Italian-made Hercules movies with Steve Reeves and his subsequent involvement with Federico Fellini — Contempt could only seem the grotesque marriage of crass exploitation and high art. (In fact, all the nude shots of Bardot were ordered by Levine after Godard considered the film done; acceding to the producer’s request as literally as possible, he even clarified the commodification process in the opening evaluation of Bardot’s body.)

Stanley Kauffmann’s review in the New Republic was characteristic of the scorn heaped on the film. It began, “Those interested in Brigitte Bardot’s behind — in Cinemascope and color — will find ample rewards in Contempt.” He went on to argue that the film’s longest single sequence, transpiring between Piccoli’s and Bardot’s characters in their flat in Rome, “can serve in all film schools as an archetype of arrant egotism and bankrupt imagination in a director….Underneath the arty prattle [of what Kauffmann termed Godard’s ‘clique’] about his supposed style, one can hear their unconscious gasps: ‘That film must cost so-and-so many thousands of dollars a minute! Any commercial hack would be concerned to make each minute count for something. But Jean-Luc doesn’t care!’ The hidden referent here is not aesthetic but budgetary bravado.”

A short while after the film’s release I invited Susan Sontag, who was at the time a literary and theater critic with some interest in film, to give a talk at my college. She had recently published an article about camp in Partisan Review that had created a flurry in the New York Times Sunday Magazine, and an article about Vivre sa vie had appeared in an ambitious new film magazine called Moviegoer. The night she came she read a still-unpublished essay called “On Style” that would be appearing in her forthcoming collection, Against Interpretation. After her talk, in a bar down the road from campus, I was shocked to hear her say that she’d been to see Contempt four or five times already. It was the first time I’d heard someone refer to the film as anything but a mess and an embarrassment, and I decided that maybe it deserved another look.

Even so, it was years before Contempt started to make much sense to me. And though today I wouldn’t hesitate to call it a masterpiece, and certainly one of the great films of the 60s — if not “the greatest work of art produced in postwar Europe,” as critic Colin MacCabe labeled it in Sight and Sound last year — I still feel more comfortable with my earlier ambivalence about it than I do with its current acclamation as a timeless, unproblematic classic. Indeed, I would argue that Godard’s eclecticism must be acknowledged and understood before one can genuinely appreciate the film.

Based on a novel by Alberto Moravia that I haven’t read, Il disprezzo (published in English as The Ghost at Noon), Contempt focuses on the relationship between playwright Paul Javel (Piccoli) and his wife Camille (Bardot), a former typist. While in Rome, Paul gets hired by American producer Jeremy Prokosch (Palance) to doctor the script for an international blockbuster, based on Homer’s Odyssey, being directed by Fritz Lang (Lang himself). Shortly after Paul is hired, in the ruins of a once bustling Italian studio (Cinecittà) that has just been sold, the writer insists that Camille ride in Prokosch’s red Alfa-Romeo to the producer’s villa outside Rome while he follows in a taxi; this flip gesture sparks the protracted on-again, off-again quarrel between Camille and Paul in their flat that takes up almost a third of the film — roughly half an hour out of 101 minutes.

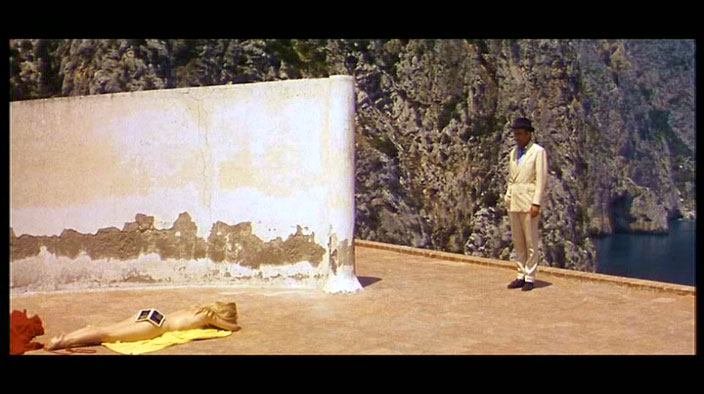

The action shifts to Capri, where the film of the Odyssey is being shot and the remainder of Contempt unfolds, charting the growing estrangement between the couple and Prokosch’s interest in an affair with Camille. Because Paul and Camille speak only French and Prokosch speaks only English (while Lang speaks German, French, and English but little Italian), Prokosch’s assistant Francesca (Giorgia Moll) plays a key role as interpreter. (She also figures at times as Prokosch’s abused mistress, and Paul makes a halfhearted pass at her, which Camille observes, at Prokosch’s villa.)

In an early treatment for Contempt, Godard describes Paul as a character from Resnais’ Last Year at Marienbad who wants to be a character in Hawks’s Rio Bravo. He also indicates that the first time you see John Wayne in Rio Bravo you don’t care where he went to school or what his father does for a living; all that matters — and all that defines him — is what he does in the present. This description essentially translates the Homeric hero into movie terms, and it helps explain why even packing a gun doesn’t suffice to make Paul an Odysseus.

Though Contempt is about a good deal more than filmmaking, Godard’s extended career as a film critic — which started in 1950 and continued well beyond the time of his early features — informs the movie at every turn. Considering a few of his major sources indicates how broad and educated his conception of cinema was at the time:

1. Michelangelo Antonioni. Paul and Camille’s exhaustive as well as exhausting scene in their significantly unfinished and mainly white-walled flat is in many ways the sequel to an almost equally protracted scene between Jean-Paul Belmondo and Jean Seberg in Breathless, though that was essentially a long seduction and this is a chronicle of growing disaffection. Unquestionably Antonioni, whom Godard interviewed at length in 1964, is the ruling influence on this scene — on its casual detachment from both characters, novelistic psychological ambiguities, protracted sense of duration, and remarkable feeling for the ebb and flow of a troubled relationship. Back in 1964, when I was blind to the Antonioni influence, I was turned off by Paul’s macho insensitivity and what I perceived as Godard’s uncritical identification with it; today I’m more inclined to read the same sequence as a profound self-critique.

Much as Antonioni was charting aspects of his relationship with Monica Vitti in all his films of this period (L’avventura, La notte, Eclipse, Red Desert), Godard was examining his relationship with Anna Karina in most of the films that immediately preceded and followed Contempt (Le petit soldat, A Woman Is a Woman, and Vivre sa vie beforehand, and Band of Outsiders, Alphaville, Pierrot le fou, and Made in U.S.A. afterward). In Contempt Godard has Bardot put on a Karina-like black wig at two separate points during the quarrel between Paul and Camille. (Antonioni has a similar wig-changing scene in L’avventura.) It’s unfortunate that Kauffmann — who was one of Antonioni’s earliest and most passionate American defenders — regarded Godard’s masterful protracted sequence in Contempt as bankrupt. To me it’s the emotional and thematic core of the film, in part because it registers with much of the same personal urgency as Antonioni’s films with and about Vitti. (The same urgency, incidentally, can be found in Roberto Rossellini’s films of the 50s with Ingrid Bergman, especially Viaggio in Italia.)

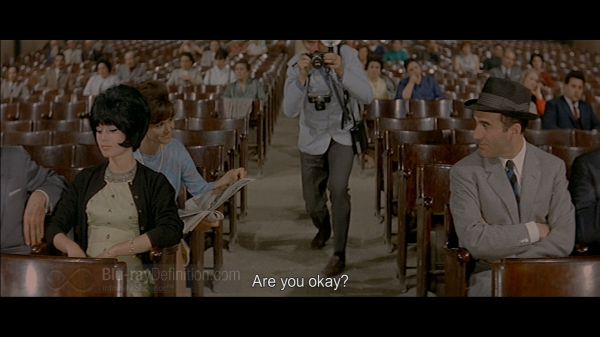

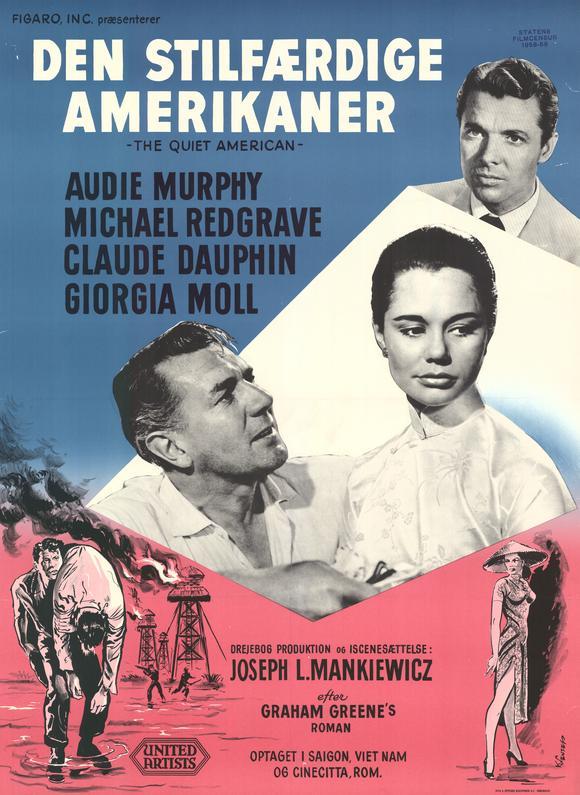

2. Joseph Mankiewicz’s The Quiet American (1958). Mankiewicz was the subject of the first piece of film criticism Godard ever published; Godard also expressed his admiration for this very writerly filmmaker as recently as the 1990 Nouvelle vague. Their affinity isn’t hard to understand: between the two of them Mankiewicz and Godard have probably made the talkiest movies in the history of cinema. The Quiet American — which Godard wrote about in 1958, declaring it the best film of that year — is not only a precedent for Godard’s epigrammatic dialogue but, more important, the inspiration for casting Moll (who plays Mankiewicz’s Vietnamese heroine) and for Godard’s fascination with the process of translation. In a key sequence in Mankiewicz’s far from faithful adaptation of Graham Greene’s anti-American novel, the middle-aged journalist (Michael Redgrave) who lives with Moll serves as translator between his French-speaking mistress and the English-speaking Audie Murphy, a younger and more idealistic American character who actually proposes to her during this scene. Moreover, Redgrave’s feeling about Murphy — which confuses sexual envy, anti-Americanism, personal differences, and moral revulsion — forecasts Paul’s own muddled attitude toward Prokosch and the prospect of selling out.

3, 4, and 5. Fritz Lang’s The Tiger of Eschnapur and The Indian Tomb (1959) and Jean-Daniel Pollet’s Mediterranée (1963). Alas, none of these extraordinary films is available in the United States. All three explain a great deal about Contempt — especially the film’s treatment of Lang and the enigmatic film within a film he’s shooting. The two Lang films, which together comprise a single work, were international superproductions shot in Germany and India; they combine a consciously naive, fairy-tale form of storytelling with Lang’s rigorous, almost abstract approach to design, framing, and editing. Though both were popular successes elsewhere, here they were released only as a dubbed, truncated, reedited single feature, Journey to the Lost City, which Lang disowned and barely anyone noticed.

Though today Godard and his Cahiers du cinéma colleagues are cited mainly as the first critics to regard Howard Hawks and Alfred Hitchcock as serious artists, in some ways their critical defense of Lang’s two Indian films — which was harder for most others, including Lang himself, to swallow — is even more important. Most critics regarded these films as pathetic and degrading hack work by a once prestigious director, almost as if someone like Ingmar Bergman had directed the current Kull the Conqueror — despite the fact that Lang was filming a script he’d coauthored in Germany in the 20s. By contrast the Cahiers critics (among them Luc Moullet, whose book on Lang Camille is reading and quoting from in the bathtub in Contempt) argued that Lang remained absolutely true to his vision and principles in these films. As one later French critic, Raymond Bellour, put it, they reveal “an inability to lie carried to the point of tragedy”; in a similar spirit, I’ve argued elsewhere that they feature the only cave in movies worthy of Plato’s. But the tawdry commercial aspects of these films blinded most critics to their honesty, integrity, and exquisite beauty, which explains their continuing absence here even on video. Yet these films are what support not only the notion of a Lang version of the Odyssey but Lang’s position in Contempt as the only uncorrupted and incorruptible figure.

Yet it seems Godard remained incapable of doing something truly Langian in the film within a film, except through a kind of abstraction. (He does a much better job of evoking Lang’s geometrical visual style in an overhead shot of Paul climbing the steps of Prokosch’s villa — actually Curzio Malaparte’s — in Capri, which harks all the way back to the Tower of Babel sequence in Metropolis.) Though Godard aims to evoke the lucid approach toward antiquity and the cosmos he associates with Lang, he’s guided by the very different example of Pollet’s 42-minute experimental film — the focus of a dreamy reverie on antiquity that Godard wrote at about the same time he was making Contempt. Pollet’s seminal Mediterranée cuts repeatedly between meditative camera movements around various subjects — Greek ruins, a Sicilian garden, a Spanish bullfight, a woman on a hospital cart, a fisherman — conjuring up a great many mysteries about their relation to one another. Seen today, Pollet’s plotless film looks a good deal like many of the lyrical interludes in Contempt.

6. Vincente Minnelli’s Some Came Running (1959). When Paul takes a bath wearing a hat and smoking a cigar, he cites Dean Martin in Some Came Running as his noble precedent. In fact a good many of the stylistic features of Minnelli’s 50s and 60s melodramas anticipate Contempt — most strikingly the bold color coding, reflected in Godard’s use of matching yellow bathrobes or towels to link Francesca and Camille to Prokosch, and elsewhere in his vibrant, emotional use of red and blue in the décor. More important, Godard at times gives big-time filmmaking (Hollywood in The Bad and the Beautiful, Cinecittà in Two Weeks in Another Town) the same satirical and grandiloquent treatment as Minnelli.

Much as William Faulkner once credited his success as a novelist to his failure as a lyric poet and Dizzy Gillespie explained his early trumpet style as an abortive attempt to imitate Roy Eldridge, what Godard can’t do is fundamental to what he winds up doing. If Contempt invents a new way of thinking about the world — combining the whole complicated business of shooting a movie with reflections on antiquity and modernity, love and filmmaking, sound and image, art and commerce, thoughts and emotions, and four different languages and cultures — it arrives at this vision mainly through a series of detours and roadblocks. Indeed, it might be argued that Godard fails as a storyteller, as an entertainer, as an essayist, and as a film critic in the very process of succeeding as an artist.

How does he fail as a film critic? Contempt begins and ends by showing the execution of a particular tracking shot. The first of these accompanies Francesca down a patch of the Cinecittà back lot while a male voice, after reciting the film’s major credits, intones the following: “‘The cinema,’ André Bazin said, ‘substitutes for our gaze a world that corresponds to our desires.’ Contempt is the story of this world.” Godard is clearly fond of this quotation, because he cites it again in both Histoire(s) du cinéma and his latest feature, For Ever Mozart. But as far as I’ve been able to determine, neither the quotation nor the attribution is correct. A likelier source is a much wordier passage by the controversial Cahiers du cinéma critic Michel Mourlet. One of the most passionate defenders of Lang’s Indian films, he wrote in 1959, several months after Bazin’s death: “Since cinema is a gaze which is substituted for our own in order to give us a world that corresponds to our desires, it settles on faces, on radiant or bruised but always beautiful bodies, on this glory or this devastation which testifies to the same primordial nobility, on this chosen race that we recognize as our own, the ultimate projection of life towards God.”

How does Godard fail as a storyteller and entertainer? The plot of Contempt proceeds by fits and starts over an afternoon in Rome and a morning in Capri, interrupted by constant digressions and labyrinthine ruminations. Palance as Prokosch is a screaming caricature of an oracular producer, Bardot the unlikeliest “former typist” imaginable. We’re supposed to revere Lang as a great artist, but the rushes of the film he’s purportedly making look simply awful. At one point Piccoli packs a gun, but he never winds up doing anything with it. When two of the characters die at the end in a car crash, Godard can’t even bring himself to show us the accident; we only hear it offscreen, then see an awkwardly posed shot of the wrecked car and passengers that resembles a freakish piece of modernist sculpture. Sometimes Godard eliminates the sound track entirely (except for the repeated motifs of Georges Delerue’s score, which Scorsese recently used in Casino); in one sequence, at a noisy audition in a movie theater, he periodically turns off the ambient sound in order to let us hear the dialogue.

In countless other ways Godard calls attention to his technique, thereby preventing us from simply following the story as story: he moves the camera back and forth between the quarreling Paul and Camille, periodically cuts to seemingly unmotivated flashbacks, fantasies, and even a flash-forward (most of which account for the three minutes deleted in the original American release), and even adds a blue or red filter in the middle of takes.

How does Godard fail as an essayist? By refusing to pursue a single linear argument or even theme, even when he isn’t telling a story, spattering his dialogue with Wise Sayings and assorted quotes from Dante, Hölderlin, Brecht, and even Lang, inserting gratuitous film references anywhere and everywhere. (We find out what’s playing at the theaters in Rome: Rio Bravo and Bigger Than Life. We see posters for Hatari!, Psycho, Vanina Vanini, and Vivre sa vie. We also know what’s playing at the theater where the auditions are being held: Viaggio in Italia.)

And how does Godard succeed as an artist? By turning the above mess into a discourse with its own kind of necessity, wasting nothing. Bazin might not have been the source of the film’s opening quote, but as the Socratic inquisitor into what cinema was, he should have been. The broken rhythms of the storytelling in Contempt and the frequent slippages between stars and characters, characters and caricatures, films and ideas about films, incidents and ideas about incidents all point to innovative ways of thinking, as Godard enters the material from different angles to tease out its hidden meanings. And if these meanings take the form of a cubist mosaic rather than a linear narrative or argument, that’s because stories and essays take us only part of the way in perceiving the modern world and its contradictions.

Erich Auerbach in “Odysseus’ Scar” — the first chapter of his Mimesis, and the best piece of literary criticism that I know — makes an extended comparison between the style of Homer and the style of the Old Testament: “On the one hand [meaning Homer], externalized, uniformly illuminated phenomena, at a definite time and in a definite place, connected together without lacunae in a perpetual foreground; thoughts and feelings completely expressed; events taking place in a leisurely fashion and with very little suspense. On the other hand [in the Old Testament], the externalization of only so much of the phenomena as is necessary for the purpose of the narrative, all else left in obscurity; the decisive points of the narrative alone are emphasized, what lies between is nonexistent; time and place are undefined and call for interpretation; thoughts and feelings remain unexpressed, are only suggested by the silence and the fragmentary speeches; the whole, permeated with the most unrelieved suspense and directed toward a single goal (and to that extent far more of a unity), remains mysterious and ‘fraught with background.'”

If Contempt has a single, overarching subject it’s the aching distance between the two styles Auerbach outlines and the two ways of perceiving the world they imply. Using these styles more broadly to describe antiquity and modernity, it should be obvious that Contempt is not simply a look at antiquity from the vantage point of modernity — Fellini Satyricon is closer to that. Contempt is something more nearly akin to the reverse: a look at ourselves as we might appear to the Greek gods. Layering one antithetical style over another — classical over modern — Godard necessarily produces a work shot through with contradictions. In terms of Auerbach’s two modes, Godard’s serene camera movements and the film’s lush, melancholy score stand in for Homeric style, as do various other signifiers of epic and odyssey. But what his camera is traversing (including the Mediterranean, as in the final shot) and what the score accompanies is generally fraught with turbulence, whether it’s obvious or not.

Godard, playing Lang’s assistant director in the film, has the last word, heard over the final tracking movement across the sea, a final command to the film crew, “Silence,” as the camera starts rolling — a command that’s then translated into Italian. Godard’s view of serenity and continuity is necessarily splintered, because the modern world is a Tower of Babel where languages and discourses compete for mastery over a purity that eludes our grasp. Not even silence is unmediated. There’s a French silence, an Italian silence, a German silence, and an American silence; maybe even a Greek silence, which the film prefers to remain silent about.