Jean Grémillon remains one of the major French filmmakers whose films are most egregiously unavailable on DVD, especially when it comes to versions with English subtitles — although I’m delighted to report that Criterion’s Eclipse brought out three of his greatest ones, all made during the Occupation, including the two that are discussed here and Remorques. This article appeared in the October 25, 2002 issue of the Chicago Reader. –— J.R.

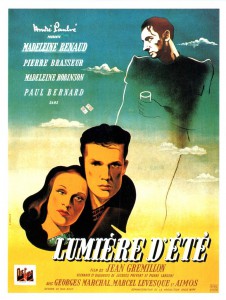

Lumière d’été **** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Jean Grémillon

Written by Jacques Prévert and Pierre Laroche

With Madeleine Renaud, Pierre Brasseur, Madeleine Robinson, Paul Bernard, Georges Marchal, and Marcel Lévesque.

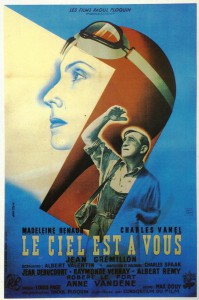

Le ciel est à vous **** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Jean Grémillon

Written by Albert Valentin and Charles Spaak

With Madeleine Renaud, Charles Vanel, Jean Debucourt, Léonce Corne, Albert Rémy, and Robert le Fort.

A friend and colleague, critic and teacher Nicole Brenez, says that the best film criticism consists of films critiquing one another. This may sound a mite abstract, but two very different masterpieces by the great, neglected Jean Grémillon, Lumière d’été and Le ciel est à vous, seem to offer a concrete example of this, as a critique of Jean-Luc Godard’s In Praise of Love, which I wrote about last week.

Both are showing this week as part of an invaluable retrospective at Facets Cinematheque (how rare screenings of both are is apparent from the lack of translated titles; the first means “summer light,” the second “the sky is yours”). Godard accuses cinema of having responded inadequately to World War II. Yet Lumière d’été and Le ciel est à vous were both made and released in France during the Occupation, in 1943 and 1944 respectively, and they are both exceptional responses to the Occupation, even to the conditions of their making. Neither film qualifies as propaganda, though the first, through the portrayal of one character’s decadence, was taken by much of the Vichy press to be hostile to the Vichy government (and as a result was eventually suppressed); the second was widely approved of and applauded by both the Vichy press and the French resistance, though according to film historian Alan Williams, it was a relative disappointment at the box office. (Electrical shortages that interrupted screenings during that period reportedly discouraged moviegoing in general; apparently the film did much better when it was rereleased after the Liberation.)

One essential criterion for judging whether such films were an adequate response to the Resistance is how much they were shown and seen. Both of these films were widely distributed, though the eventual suppression of Lumière d’été makes one wonder whether the more covert aims of Le ciel est à vous counted for more in the long run. One also has to wonder whether Godard is being realistic in his judgments about what constitutes honorable work under such circumstances. In this country, critics of films produced under totalitarian regimes often have unrealistic expectations. For instance, some reviewers have faulted contemporary Iranian filmmakers for “playing along with the mullahs” by avoiding politically contentious material. But filmmakers from every country avoid politically contentious material, so it seems churlish to ask those living under repressive regimes to take greater risks than anyone else. Moreover, how can we evaluate decisions made in other countries? Few people who’ve seen Abbas Kiarostami’s latest feature, 10, could have anticipated that Iranian censors would ask him to delete well over half its footage. For these reasons, any moral judgments I might have about films made in occupied France around the time I was born are only tentative and speculative.

***

Six features by the enigmatic Jean Grémillon (1901-’59) are playing at Facets this week (I’ve viewed five of them, all worth seeing). Trained as a musician and composer, he first came into contact with films professionally when he played in a small orchestra that accompanied silent pictures, and many critics have noted that he tended to structure his films in movements, as if they were pieces of music. (He was also especially creative when it came to his sound tracks; one striking “flashback” in Lumière d’été is created exclusively through sounds while the camera remains firmly anchored in the present.) He started out making documentaries and experimental films; aspects of them can be found in his subsequent features, which were always populist by design. I suspect that his career was so checkered — he was forced to work in Spain in the 30s and on documentary shorts throughout most of the 50s — in part because of the cross-purposes and temperamental conflicts of an intellectual leftist member of the French Resistance who wanted to reach a wide public. (His bisexuality may have intensified those conflicts.) He was sufficiently well-known within his profession to have served as president of the Cinémathèque Française from 1943 to 1958, but when he died the following year — on the same day as matinee idol Gérard Philipe — he’d largely been forgotten.

Judging by his films, he was a protofeminist. He had a fruitful association with Madeleine Renaud in four of his best films, made between 1938 and 1944: L’étrange Monsieur Victor (also showing at Facets), Remorques, Lumière d’été, and Le ciel est à vous. A member of the Comédie Française for a quarter of a century (1921-’46) who left the company to form her own with Jean-Louis Barrault, Renaud appeared in a dozen films between 1931 and 1936; after that Grémillon was the only filmmaker she worked for until she played in Max Ophüls’s Le plaisir (1951). Part of what’s so remarkable about her four Grémillon roles is their range and their capacity to undermine patriarchal stereotypes: she plays an apparently meek housewife turned potential adulterer in L’étrange Monsieur Victor (opposite the extraordinary Raimu in the title part), a neglected “older woman” juxtaposed with a younger female star in Remorques and Lumière d’été (familiar parts to which she gives relatively fresh spins), and, most surprising, a hardworking housewife and mother turned aviatrix heroine in Le ciel est à vous.

***

One reason Grémillon has never come fully into focus, even in France, is that he can’t be readily approached as an auteur — unlike, say, the screenwriter for Lumière d’été, Jacques Prevert.

Ironically, it was Prevert not Grémillon who was blamed in the Vichy press for the film’s “counterproductive” attitudes (a distinction Grémillon disavowed at the time), most of these having to do with the depiction of a rural aristocrat named Patrice (Paul Bernard) who’s gradually exposed as perverted and evil — though, to be fair, the far-from-Vichyite André Bazin praised the film’s cinematic expressiveness while decrying “its bottom-of-the-barrel scrapings of Prevertian wit.” (It’s sad but true that auteurist traces tend to be more visible in an auteur’s lesser efforts.)

The entire film is set in a remote mountain range dominated by three locations: the construction site of a dam, a swanky if mainly empty hotel with a commanding view, and a nearby chateau lorded over by Patrice. A young dress designer named Michele (Madeleine Robinson), offered a lift on the road by Patrice, turns up at the hotel to await the arrival of her boyfriend Roland (Pierre Brasseur) — a deranged alcoholic artist who maniacally spouts most of the “Prevertian wit” once he eventually materializes. Meanwhile she encounters Patrice’s lover Christiane (Renaud), a former dancer who runs the hotel, and Julien (Georges Marchal), one of the dam workers, who accidentally enters her room one night and promptly falls in love with her. There’s also a quirky hotel servant who greets every statement with a philosophical “Why not?” (played by Marcel Lévesque, the same wonderful ham who played Mazamette in Louis Feuillade’s 1916 serial Les vampires), a couple of other hotel guests, Patrice’s gardener, and several other construction workers. The characters are clearly split between wealthy and working-class, with Patrice and Christiane, thanks to their money, wielding the most power. When Patrice commissions the penniless Roland to paint a room in his chateau so that he can woo Michele, parallels between his scheme and Nazi manipulations of the French populace aren’t hard to find; the key is to reformulate the situation strictly in terms of class differences and interactions, with money taking the place of state and police power.

This juxtaposition of classes is one of the reasons Jean Renoir’s The Rules of the Game (1939) seems an obvious reference point, and it’s a tribute to Grémillon’s mastery that his film never crumples in comparison with Renoir’s supreme masterpiece. Another common trait is a climactic masked ball that turns rowdy, carnivalesque, and deadly (as well as Prevertian, anticipating the final sequence of the 1945 Children of Paradise in many particulars). With Roland dressed as Hamlet (accompanying Michèle as Ophelia) repeatedly proclaiming that something is rotten in the state of Denmark, one can easily figure out why the Nazis were suspicious: the whole plot hinges on the manipulations of people in positions of power.

***

Le ciel est à vous is something else again — a working-class love story that received the approval and support of collaborationists because it validated humble home values. Yet according to film historian Bernard Eisenschitz, it was also “taken by French audiences as a call to arms.” Probably this was because it celebrated soaring beyond earthbound limitations, including those of the humble home values it seemingly validated. Even the film’s title might be said to support this second reading: saying the sky is yours implies that the ground is theirs.

In short, the film can be seen as a somewhat contradictory multipurpose object that allowed different viewers in 1944 to find what they were looking for. That doesn’t mean it’s a work without integrity or purpose; subtleties and ambiguities in the characters, performances, and plot make it only superficially superficial. Its extreme populism may look hokey at first, yet the shadings and ambiguities transform it into something complex without ever being condescending or patronizing. One way it does this is to subtly undermine the idea of patriarchy without ever undermining its supposedly patriarchal hero (Charles Vanel), an extremely likable, self-effacing, and entirely believable auto and plane mechanic. (Vanel’s and Renaud’s performances deserve to be counted among the enduring glories of French cinema.) Furthermore, while the story is said to be based on fact, it quickly becomes apparent that the film’s main underlying impulse is mythic rather than factual.

It opens with a long pan revealing first a shepherd leading a flock of sheep (a mass of white) and then a clergyman-teacher leading a group of orphaned boys (a mass of black). The orphans, who keep reappearing in the film as a kind of mysterious leitmotiv, are identified by a sign as belonging to an orphanage in the town of Villeneuve, the destination of the film’s central family — Pierre Gauthier (Vanel); his wife Thérèse (Renaud); Therese’s bossy mother, whose values are relatively petit bourgeois; and the couple’s two children, a son and a daughter who’s a gifted pianist. The multiple physical and logistical facts of the family’s move are handled with an offhand realism and a kind of novelistic detail that adroitly introduce us to all the members while giving us a solid sense of their interactions.

That they’re moving from a garage in the countryside to a somewhat larger one in town is a sign that they’re a “modern” family, not simply salt-of-the-earth peasants. And though Pierre is a conventional patriarch on the surface, the film shows us at the outset how much of Thérèse’s labor is necessary to make his new garage operational. Even her eventual heroism as a pilot is never allowed to detract from her competence and attentiveness as a domestic workhorse, and despite a few conventional outward appearances, we’re never in any doubt that she’s the one who holds the family together. Only through a series of carefully planned plot developments do we learn that Pierre is familiar with plane engines (knowledge picked up during World War I and revealed at the opening of a local airfield); that he loves flying, which Thérèse persuades him to give up; that after she takes a brief plane ride she falls in love with flying herself; and that his love for her and for plane engines combines with her own passion for flight to become a shared obsession. Ultimately this leads her to attempt a record-breaking flight — an event the film milks for a maximum of suspense without showing any part of the flight. Indeed, part of Grémillon’s singular achievement is to create a film about flying while remaining exclusively on the ground, without making us feel that his story is an allegory.

Most important, we wind up believing in this couple without ever feeling that the film is idealizing them. Their obsession eventually leads Pierre to sell his daughter’s new piano over her objections — though she secretly continues to take lessons from a sympathetic teacher (Jean Debucourt) — which shows us simultaneously how their passion can be blinding and how it can be matched by other passions. I should also point out that Noël Burch and Geneviève Sellier reveal in their 1996 book La drôle de guerre des sexes du cinéma français, 1930-1956 (“The ‘Funny War’ of the Sexes in French Cinema, 1930-1956”) that the couple’s favorite song, “The Time of Lilacs and Roses,” played by the piano teacher while they’re shopping for their daughter’s new piano, is a covert allusion to “Lilacs and Roses,” the first Resistance poem written by Louis Aragon in 1940 and distributed by the French underground; the grandmother’s favorite song, the march from Aïda, which the teacher mocks, was played when French troops left for the front during World War I. I suspect that such details functioned as in-jokes for the benefit of a few members of the Underground; they evidently escaped the attention of the Nazis. More crucial in defining Le ciel est à vous as a Resistance film is its seductive demonstration of how ordinary people can rise beyond their circumstances. If this message got sold to collaborationists as well, so much the better.