From the January 6, 1989 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

For me, the ten best movies of 1988 are the ones I would profit most from seeing again and the ones I’ve profited most from thinking about. Their value, in other words, lies not merely in the immediate pleasure they offered but also in their aftereffects — the way they set with me for weeks and months after I saw them, sometimes growing and ripening with time.

I tend to be wary of critics’ lists and awards that are unduly weighted toward recent films — particularly because it’s much harder to evaluate a movie at the time of its release than it is weeks, months, or even years later. Perhaps the key occupational hazard of film critics is the pressure to remain stuck in a continuous present, and to serve the whims of the marketplace by confusing what’s recent with what’s genuinely new. Measuring a given week’s offerings only against each other narrows the difference between criticism and advertising by basing everything on consumption — reducing the universe of films to the few releases that happen to be available for consumption at any given moment rather than reflection.

On the basis of my own reflection, it turns out that six of my favorite movies of 1988 opened in Chicago during the first half of the year; I saw a couple others either then or earlier, and the remaining two in July and September. I point this out not to downgrade the films I saw from October on — the best of which were Bird, The Death of Empedocles, Talk Radio, and Torch Song Trilogy — but to suggest that I’m not yet far enough removed from them to know whether or not they belong on the list.

By the same token, I should point out that my ranking of the films below isn’t entirely consistent with the way I originally rated them. Once again, the difference between immediate marketplace considerations and subsequent reflection is operative here, and it’s worth adding that the context in which stars are assigned to movies should never be regarded as fixed or immutable, any more than ten-best lists or critics themselves should be. It’s an expedient fiction to pretend otherwise, but the measurement of value in art is at best a game or a manifesto — it can never be accorded the status of a science.

1. Mix-Up. My favorite film of 1988 received its Chicago premiere as part of Barbara Scharres’s exciting “Stranger Than Fiction” series at the Film Center in February; it’s a 63-minute documentary in English made by French filmmaker Francoise Romand in 1985. While it may strike some as an obscure choice, it has actually received a respectable amount of U.S. exposure for a film of this kind–having appeared both on PBS and at New York’s Film Forum. But even if it were ten times better than it is (a difficult hypothesis, for it already seems virtually flawless), I doubt that it would have received much more attention than it has; it’s an unconventional documentary with an unconventional running time, which automatically guarantees it less mainstream status than any commercial stinker that comes up the pike.

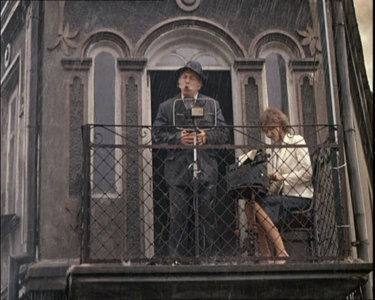

This is not to suggest that there’s anything difficult or inaccessible about Mix-Up. Romand’s subject is the true-life mix-up of two baby girls at a hospital in Nottingham, England, in 1936 — an error that wasn’t confirmed until 1957, by which time each child had grown up in the wrong family. Romand’s approach to this subject and the two extended families involved has a rare openness and originality, including the radical conviction that there aren’t necessarily hard and fast distinctions between the problems of life and the problems of art. Involving virtually all of the participants in this story, she fashioned a combined reenactment and analysis of a complex family saga. Her highly stylized presentation of what it all meant is at once a collective psychoanalysis, a dense and humorous 19th-century novel with Dickensian characters, an essay on representation, a poetic integration of portraiture with domestic architecture, and a tragicomic existential melodrama.

Having seen this film about half a dozen times, I’ve found that it grows in power and resonance with every viewing. Romand’s attack on her material seems intuitive rather than theoretical or intellectual, but the seriousness and thoroughness with which she pursues it — not only charting the process of two families reassessing their behavior and experiences, but also contriving to bring this process about — create a formal beauty and a witty precision in framing, pacing, editing, use of music, and mise en scene that are inseparable from the film’s ethical and philosophical project.

2. Brightness. Souleymane Cissé’s breathtakingly beautiful feature, the greatest African movie I’ve ever seen, turned up briefly at the Film Center last July as part of the Blacklight Film Festival. The film had already received the special jury prize at the 1987 Cannes Film Festival, and I saw it in March at the San Francisco Film Festival. It’s reappearing at the Film Center in a longer run this week, when the task of writing this ten-best list precludes my devoting a full column to it.

Perhaps it’s just as well, for the singular magic of Brightness — which combines a simple, matter-of-fact presentation with mystery and wonder that charge every instant — eludes easy description. A mythical fantasy set in a remote culture of pre-16th-century Mali, it follows the quest of a young tribesman named Nianankoro, who seeks to discover the science of the gods; his mission sets him in direct conflict with his spiteful and jealous father, who uses his own magic spells in an effort to kill him. Shot in gorgeous Fujicolor, this is a spellbinding oedipal adventure about ritual and initiation, enhanced by a rhythmically mesmerizing sound track that weaves voice, music, and sound effects into a spare tapestry.

Cissé’s episodic plot evokes westerns, Arthurian legends, sword-and-sorcery epics, and science fiction (in the autumn Sight and Sound, Gilbert Adair draws some intriguing parallels with 2001 and Star Wars) while remaining African to the core, in its overall ambience as well as its remarkable locations. It’s depressing to think that if Cissé had had the power or the bad taste to use Tom Cruise or Tom Hanks in blackface for the lead instead of the wonderful Issiaka Kane, he’d have botched his masterpiece beyond belief, but he still would have gotten some attention from the TV reviewers, Time, Newsweek, and the New Yorker. The mainstream consensus appears to be that any African movie, no matter how great, hasn’t a prayer of being treated as seriously as any Cruise or Hanks movie, no matter how atrocious.

3. Housekeeping. Bill Forsyth’s first American feature and the swan song of Columbia Pictures’ David Puttnam, which opened at the Fine Arts in January, proved to have the loveliest and most fluid story-telling style of any American movie released all year. A sensitive adaptation of Marilynne Robinson’s lyrical novel, it managed to approximate the book’s poetic atmosphere without being too literary or seeming anything less than a film. Christine Lahti is plausibly, with Barbara Hershey, the most accomplished American actress now working in movies, and her Aunt Sylvie is one of her most indelible (if least showy) performances — finely tuned both to the evocative period setting and to the two nonprofessionals who play her orphan nieces. Similarly, Forsyth’s superb use of locations and landscapes in and around Nelson, British Columbia, his feeling for popular songs, and his delicately nuanced humor are all experienced as deft painterly touches rather than as directorial grandstanding. “Haunting” may be the most overworked adjective in criticism, but the film’s grasp of loneliness, eccentricity, restlessness, and nature creates a voluptuous sense of mystery that revitalizes the word’s meaning.

4. Repentance. It’s possible that glasnost has yielded the most interesting group of Soviet films to appear since the early sound masterpieces of Dovzhenko, Kuleshov, Pudovkin, and Vertov. (I’m excepting isolated revelations such as Donskoi’s Gorky trilogy, Eisenstein’s Ivan the Terrible, Solntseva’s The Enchanted Desna, and Tarkovsky’s Stalker.) The most exciting delayed releases I saw in 1988 included Panfilov’s The Theme (1959), Konchalovsky’s Asya’s Happiness (1967), and Askoldov’s Commissar (1967). But Tengiz Abuladze’s Repentance (1984) was in many respects the best of the lot for the spirited savagery of its satire, the color and imagination of its mise en scène, and the provocative nature of its historical meditation on despotism over three generations.

Even though more than 60 million Russians have seen Repentance, the sheer otherness of Soviet cinema has presented a certain stumbling block for most U.S. audiences. It is hard for us to see what makes Asya’s Happiness contemporary with Bonnie and Clyde, or The Theme contemporary with Kramer vs. Kramer. Yet paradoxically, while Repentance adopts poetic and narrative conventions that are even further from our own than the naturalism of Asya’s Happiness or the literary first-person narration of The Theme, the freewheeling uses of allegory, Gogolesque fantasy, and dreamlike surrealism impart an emotional richness that sustains Abuladze’s intricate structure over 150 minutes. Avtandil Makharadze’s bravura dual performance as the despotic mayor and his son — a tour de force every bit as impressive as Jeremy Irons’s dual role in Dead Ringers — offered the best male acting I saw in any film this year. Unlike most of the other films on this list (apart from Housekeeping and Hairspray), Repentance is currently available on video, so readers who missed this remarkable picture last May at the Music Box can still check it out.

5. Wings of Desire. Wim Wenders’s trilingual romantic reverie about Rilkean angels in contemporary Berlin, which opened at the Fine Arts in July, was his first real hit in the U.S. What this indicates, I think, is not so much that this movie is superior to its predecessors as that Wenders’s growing international reputation is finally beginning to take hold over here. While the film ends lamentably in a blaze of unearned affirmation — one of the lead angels (Bruno Ganz) descends to earth, becomes human, and falls in love with a trapeze artist (Solveig Dommartin) — the first hour or so is so fresh and exhilarating as it swoops over and across Berlin that it can ultimately make up for any number of forced landings. Benefiting from the highflown rhetoric of cowriter Peter Handke, the pristine black-and-white cinematography of Henri Alekan (with privileged bursts of color), and the delightful charismatic presence of Peter Falk playing himself, Der Himmel über Berlin harks back to some of the great city films of the 1920s in its breathless ambition to embrace the soul of a city through its multiplicity.

6. Who Framed Roger Rabbit. An old-fashioned entertainment in the grand style, this encounter between live-action film noir and animated cartoons set in 1947 Hollywood had more energy and small-scale inventiveness than most of the other 1988 blockbusters combined. This is due in part to the happy, productive premise hit on by the diverse creative talents involved including animator Richard Williams, director Robert Zemeckis, writers Jeffrey Price and Peter Seaman, actor Bob Hoskins, and presiding gurus George Lucas and Steven Spielberg. Though the result has all the built-in limitations of a formula that’s formulaically applied, the participants outdid themselves in the zeal and the affection for their sources they brought to the enterprise. Prior to the film’s wide release in June, its chances for commercial success were believed to be far from certain. Now that it has settled into our lives with the ubiquity of a Big Mac, it still has surprisingly good credentials for a piece of Hollywood silliness — including the capacity to disturb as well as amuse.

7. King Lear. Jean-Luc Godard’s best movie since Passion remains one of his most neglected — in part because of its prodigious Dolby sound track, which few spectators anywhere were lucky enough to hear properly. Even Cahiers du Cinema, which usually can be counted upon to give every new Godard release extensive coverage, virtually clammed up about this one, perhaps because the picture’s use of English (including Shakespeare) was more than they could fathom. The movie, which turned up at the Music Box in April, has the most bizarre cast of the year — Woody Allen, Leos Carax, Burgess Meredith, Godard himself, Norman Mailer, Mailer’s daughter Kate Miller, Molly Ringwald, and Peter Sellars. Apart from Meredith as Lear, virtually all of these actors were used against the grain and in contradistinction to their usual roles and functions. Indeed, as an avant-garde film, King Lear was even less consumable — as narrative fiction, as documentary, as satire, as a concerted program of any kind — than the more accessible Talking to Strangers or Uncommon Senses (see below), but it was packed nonetheless with beauty, invention, humor, and energy.

8. Talking to Strangers. Rob Tregenza’s first feature, a series of nine ten-minute-long existential encounters in Baltimore filmed in widescreen 35-millimeter and Dolby sound, constituted in some ways even more of an assault than Godard’s Lear on the Cinematic Apparatus as it’s presently constituted — the institution regulating the production, distribution, exhibition, promotion, consumption, and discussion of movies. With a curious combination of sophistication and naivete, virtuoso camera work and amateurishness in other areas, Tregenza appears out of nowhere and confounds the system even more than Godard does by creating a few new rules of movie watching that can’t be, comfortably filed away under categories governing other films — even other films by one producer/writer/director/cinematographer. (The movie still lacks a distributor, and the Film Center, which showed it four times in November, has so far offered its most extended run to date.) Raw and cantankerous enough to be immensely irritating in spots as well as provocative, it entails a number of risks for the spectator as well as for Tregenza (who elected in advance to shoot only one take per scene), and invites diverse forms of engagement — direct, detached, oblique, amused, uncertain, horrified, bewildered — without ever sliding into easy effects or simple ambiguities.

9. Uncommon Senses: Plain Talk & Common Sense. Jon Jost’s 11-part state of the union address, which showed at Chicago Filmmakers in August, was the year’s best film essay and perhaps the most wide-ranging effort of an American independent. Jost’s eighth feature in 15 years, it testifies to his persistence in making films despite budgets that probably wouldn’t cover the coke costs of a standard Hollywood feature and a U.S. audience that remains only a pitiful fraction of the constituency that he can count on in England, where his films are shown on Channel Four. The irony is that Jost’s film is essentially an American broadside addressed to Americans. No less ironic is the picture’s own multifaceted critique of the multifaceted thrust of our Whitmanesque rhetoric as Americans, our tendency to get lost in details. Blending poetry and didacticism, Jost has interesting things to say about the form as well is the substance of our thoughts about our country–the structuring absences in our understandings — and he says them, for the most part, with a purposeful clarity that lives up to his title.

10. Hairspray. Who would have guessed that John Waters could direct a movie this engaging? Who, indeed, would ever have guessed that Waters was a director at all? From Mondo Trasho (1969) on, his talent has been exclusively a matter of writing and casting — until we get to this rough gem, his first mainstream effort, which opened here in March, and which represents almost as much of a quantum leap in filmmaking as Tough Guys Don’t Dance did for Norman Mailer.

As a writer, Waters has always been more of a humorist in the Will Rogers vein than a storyteller. As his recently published screenplay Flamingos Forever (an unfilmed sequel to Pink Flamingos) makes clear, his unsubtle approach is to lay out one outrageous detail or incident after another, as if with a trowel, with little concern for intricate plotting or shapely narrative; and Hairspray, which culminates in the same messy pandemonium that all his movies aim for, is not substantially different in this respect.

But consciously or not, Waters’s first period movie — focusing on the integration of a popular afternoon TV dance show in 1962 Baltimore — has brought him out of the closet politically as well as concentrated his energies conceptually. With the help of precise memories of rock tunes, clothes, hairstyles, and dance steps, and a hot, plump, and sassy teenage lead (the fabulous Ricki Lane), he has finally democratized his comic community. By integrating Divine (in what proved to be his last performance) in a much broader social context than usual, Waters improbably came up with one of the few politically progressive mainstream entertainments of the year that wasn’t infected with some sort of ideological incoherence — an antielite, integrationist, period rock musical farce that brightened the year considerably.

Apart from the best end-of-the-year titles and also-ran glasnost entries already cited, there are at least a dozen other new movies that nearly made it onto my ten-best list; they’re listed here alphabetically: Castaway (never released in Chicago but on video), Coverup: Behind the Iran Contra Affair, High Season, Hotel Terminus: The Life and Times of Klaus Barbie, The Land Before Time, Little Dorrit, Monkey Shines: An Experiment in Fear (perhaps the year’s most underrated commercial movie, it deserves to be rediscovered on video), School Daze, Sleepwalk, They Live, Tucker: The Man and His Dream, and Wedding in Galilee. Mélo, which had a commercial run this year, is missing from my top ten only because an earlier Chicago Film Festival screening permitted me to include it in last year’s list.

For respectable runners-up, here are 20 more titles, again listed alphabetically: The Accused, Bull Durham, Candy Mountain, Dead Ringers, Double messieurs, Falkenau, the Impossible: Samuel Fuller Bears Witness, Full Moon in Blue Water, The Funeral, The Last Temptation of Christ, The Lighted Field, Manifesto, Matador, The Moderns, Le paltoquet, Shy People, Stormy Monday, Tommy Tricker and the Stamp Traveller, Under Satan’s Sun, A World Apart, and A Zed & Two Noughts.

Special recognition should be given to four exceptional films of the past that turned up here for the first time during the Film Center’s Spanish retrospective: Life in Shadows, Nine Letters to Berta, Paloma Fair, and, above all, The Tower of the Seven Hunchbacks. Another special award should be given to United Artists for the successful rerelease of the galvanizing The Manchurian Candidate (1962), followed by a raspberry to the major studios (apart from Disney) for failing to follow this up with any other rereleases of neglected masterworks from Hollywood’s bottomless past.

Last year, I inaugurated the F.W. Murnau Award, to be given each year to a film that provokes a radical revision in our sense of film history–the film can be young or old in years, but must be brand-new in spirit. Last year’s recipient was Louis Feuillade’s French serial of 1915-16, Les Vampires, although I suppose it also could have gone to my favorite new film of 1987, Tian Zhuangzhuang’s The Horse Thief from the People’s Republic of China — a film that was made, according to the director, for the 21st century. (Ironically, the same director is currently at work on a film about the impact of break dancing on Chinese youth.)

There was no real counterpart to the Feuillade serial this year, but there was a counterpart of sorts to The Horse Thief — a film that returned to the primal sources of cinema to conjure up an aweinspiring universe that is at once completely different from our own and spiritually and mythically congruent with many of our deepest impulses. I’m thinking of Souleymane Cissé’s Brightness, another movie made for the 21st century, and the only absolute must-see masterpiece in this list that is currently playing in Chicago.