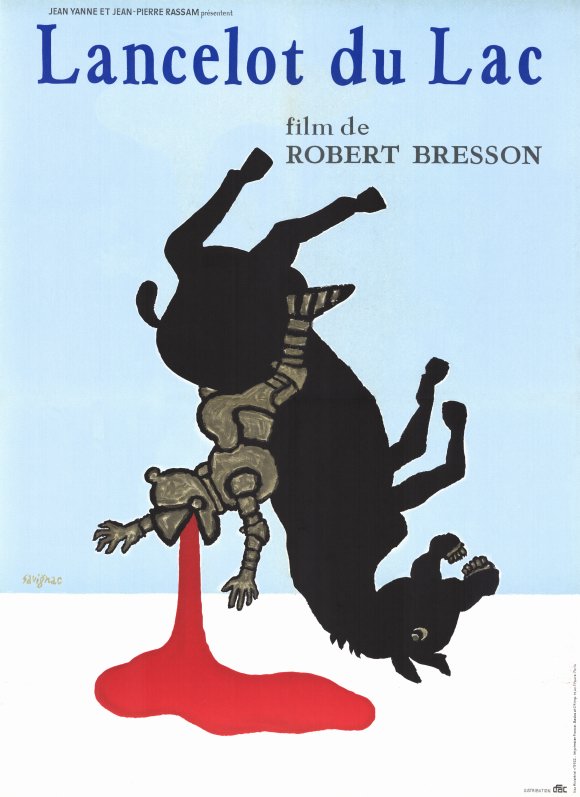

From the Summer 1974 issue of Sight and Sound. — J.R.

The Rattle of Armor, the Softness of Flesh: Bresson’s LANCELOT DU LAC

LANCELOT DU LAC embodies the perfection of a language that has been in the process of development and refinement for over thirty years. If it stuns and overwhelms one’s sense of the possibilities of that language— in a way, perhaps, that no predecessor has done, at least since AU HASARD BALTHAZAR — this is not because it represents a significant departure or deviation from the path Robert Bresson has consistently followed. The source of amazement lies in the film’s clarity and simplicity, a precise and irreducible arrangement of sounds and images that is so wholly functional that nothing is permitted to detract from the overall narrative complex, and everything present is used. It is a film where the rattle of armor and the neighing of horses are as essential as the faces and bodies of the characters, where indeed each of these elements serves to isolate and define the importance and impact of the others.

The sheer rawness of what is there disconcerts, but it shouldn’t lead one to focus unduly on what isn’t there, or track down some elusive clue to the Bressonian mystery. To a certain extent, Bresson’s films are about mystery, but their manner of arriving there is always quite concrete, just as the fictions of Kafka and Beckett are carefully constructed around certain principles of omission. Filling in these omissions is an act that every spectator/reader has to perform on some level, but anyone wishing to describe a Bresson film —as opposed to the experience of one — is obliged to leave these “white spaces” intact rather than attempt to fill them in, for otherwise he runs the risk of merely taking his own pulse. The evidence, one can argue, is clearly intelligible to the eyes and ears, if only one can look and listen. For this reason, it seems useful to speak here of Bresson’s art as one of immanence, not one of transcendence, and one where the inside is always revealed by remaining on the outside. “There is a nice quote from Leonardo da Vinci,” Bresson has remarked, “which goes something like this: ‘Think about the surface of the work. Above all think about the surface.'”

Another relevant quote: “Le cinéma n’est pas un spectacle, c’est une écriture.” Following a Bressonian law of contrast, it is only with the most “spectacular” of his subjects that the implications of this distinction become most cogently demonstrated. Apparently Bresson first made this statement at a Cannes press conference in 1957, shortly after UN CONDAMNÉ À MORT S’EST ECHAPPÉ (A MAN ESCAPED) was shown; even then, LANCELOT was already something more than just a twinkle in his eye. It is a project he has nurtured over twenty years — periodically announced as his next film, and periodically postponed because of the problems of financing it.

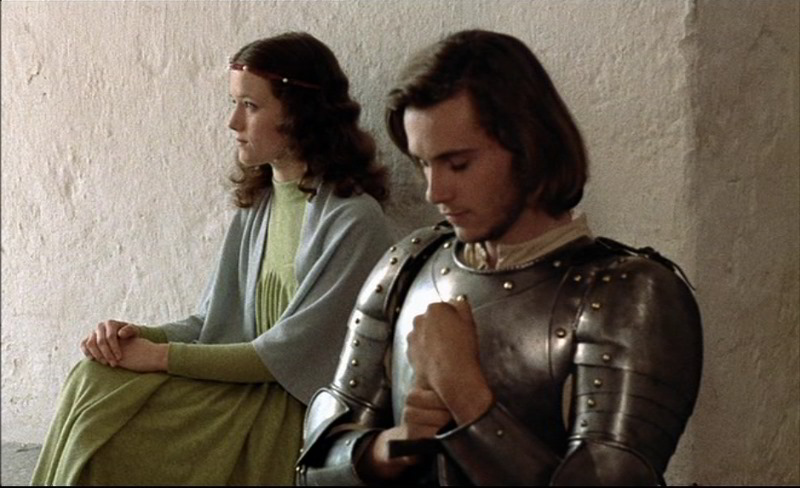

One indication of the sustaining power of his dream — a blend of chance and predestination oddly echoing the metaphysics of his fictional world — can be seen in his selection of Laura Duke Condominas to play Guenièvre, a decision initially reached when he came across a photograph of her, with no prior information about who she was. It was only afterward that he discovered she was the daughter of Niki de St. Phalle, codirector (with Peter Whitehead) of the recent film DADDY — and his original choice for Guenièvre some two decades ago.

The shooting, which lasted nearly four months, took place in the Vendée region (including the Ile de Noirmoutier) last summer; the sound mixing alone took three and a half weeks. To my knowledge, there are only two facets of Bresson’s dream that remain unrealized. He was unable to shoot the film in separate English and French versions, a desire he spoke of in an interview with Godard eight years ago. (As I write, an English-dubbed version is being prepared.) And as a concession to the producer, he has agreed to call the film LANCELOT DU LAC rather than LE GRAAL, the title given to his shooting script.

In all his previous films since LES DAMES DU BOIS DE BOULOGNE, Bresson’s procedure has been either to work closely with a preexisting text (Bernanos’s in LE JOURNAL D’UN CURÉ DE CAMPAGNE and MOUCHETTE, Dostoevsky’s in PICKPOCKET, UNE FEMME DOUCE and QUATRE NUITS D’UN RÊVEUR, André Devigny’s in UN CONDAMNÉ À MORT, historical records in PROCÈS DE JEANNE D’ARC) or to invent a completely original narrative (BALTHAZAR). In LANCELOT, he has used the background and characters of Arthurian legend as the basis for an original story, systematically eliminating all the fantastic elements. The magic of Merlin and the Lady of the Lake are totally absent, and all we see of the Grail is an image that appears behind an early title that sketches the story’s background — an emblem that briefly recalls the cross appearing at the end of LE JOURNAL D’UN CURÉ DE CAMPAGNE.

The remainder of the legend has been tailored to suit Bresson’s purposes. As in the final section of the thirteenth-century Vulgate Cycle [1], the central focus is on the adulterous affair between Lancelot and Guenièvre, seen within the wider context of the unsuccessful Grail quest (virtually over before the film begins) and the dissolution of Artus’s kingdom. Many of the same incidents are included: Mordred’s plot to expose the adultery to the king, Lancelot’s appearance at a jousting tournament in disguise, his recovery from his jousting wound in Escalot, his subsequent rescue of Guenièvre, and, after the siege of the castle of the Joyeuse Garde, his decision to return her to Artus. On the other hand, it appears that all of Bresson’s characters are considerably younger (although the girl who falls in love with Lancelot in Escalot is more or less “replaced” by an old peasant woman who shelters and cares for him); Lancelot dies not in a hermitage but on a battlefield; and an enormous amount of the plot is simply stripped away.

For that matter, according to Michel Estève [2], neither the tents nor the Round Table nor the chess game nor the wooden tub in which Guenièvre bathes belongs to the period, all of them constituting conscious anachronisms on Bresson’s part. This is a distinctly modern LANCELOT, in striking contrast to the relatively “medieval” atmosphere of Bresson’s last two films, both set in contemporary Paris, where the gentle creature in UNE FEMME DOUCE often suggested a lonely maiden in a tower waiting to be rescued, and the dreamer in FOUR NIGHTS OF A DREAMER resembled a wandering knight in search of a pure love that was equally hopeless. The sense of elongated durations and passing seasons that we associate with the romances of Chrétien de Troyes is more evident in BALTHAZAR, or even in John Ford’s THE SEARCHERS, than in the tightly compressed episodes of LANCELOT, where action and event is all.

The comparison with Ford is hardly gratuitous: LANCELOT is surely the closest thing we can ever hope to get to a Bressonian Western or adventure film, although it also achieves a tapestrylike stillness in certain scenes that plays against the livelier movements. The use of simply repeated motifs — like Guenièvre’s lighted window, the sound of a crow punctuating her brief moments with Lancelot in a hayloft, or separate shots of a riderless horse and a bird in the closing sequences — recall the methods of a twentieth-century medieval” poem like e. e. cummings’s “All in green went my love riding,” where certain words (red, deer) are reiterated to create an overall tableau effect, as in the following lines:

Four lean hounds crouched low and smiling the merry deer ran before.

Fleeter be they than dappled dreams the swift sweet deer the red rare deer.

Four red roebuck at a white water the cruel bugle sang before.

Most modern of all, perhaps, are the characters of Guenièvre and Lancelot, although the specific signs of their modernity are not at all easy to pinpoint. The scenes between them seem to adhere rather closely to the courtly tradition, and the spiritual malaise affecting Lancelot — torn between his love for Guenièvre, his vow to god to end their adultery, and his loyalty to Artus — contains no discernible elements that are added to the legend. And yet the absence of any psychology, the elliptical exposition of their feelings, and the degree to which Bresson isolates them from their environments and defines them in relation to each other, all serve to give them unmistakable contemporary reverberations. And the anonymous scenes of war and carnage that enclose their story register with an effect that is even more timely, exposing a dark terrain where blood is being spilled today.

(1) In a dark forest, two broadswords meet and clash. The camera pans back and forth, following the clanking movements of the unidentifiable armored figures as they continue to fight. One sword is raised, and in one fell swoop the other figure is decapitated. A stream of blood rushes from the stump, spilling on the ground.

(2) In a dark forest, an unidentified armored knight and his horse are wounded. Close-up: an arrow has pierced the horse’s skull over one eye. Cut to a bright shot of a dark bird diving in an empty white sky. The knight slowly rises to his feet, sword in hand, and leans against a tree. Cut to a riderless horse galloping through the forest. The knight utters a single world, “Guenièvre“: we recognize the voice as Lancelot’s. He drops his sword and collapses with a heavy rattle on a pile of armored bodies. Cut to another shot of the bird in the sky. Lancelot’s head drops with a metallic shudder and his body becomes still.

The appalling violence that opens and closes LANCELOT presents us with war as anonymous and indifferent slaughter, with faceless phantoms in the darkness battling and perishing beneath heavy armor that instantly turns into scrap metal as soon as the bodies become mute. The gush of blood from the decapitated knight and the last word of Lancelot are the only concrete signs that we are witnessing men and not machines, death and not an abstraction of death.

Bresson has always been unusually lucid about his working methods. In various statements over the years, he has repeatedly outlined the following strategies: (1) Use individuals without any previous acting experience and instruct them to recite their lines as tonelessly as possible, without expression. (2) Shoot always in natural locations. (3) Replace an image with a sound whenever possible. (4) Structure visual “syntax” not around single images but around the relationships between images — a process partially arrived at by favoring images that are relatively flat and nonexpressive, neutral and uniform.[3] (5) More generally, pare away everything that is “unnecessary,” that is, inorganic.

The rigor of Bresson’s economy is beautifully apparent in the first lines of dialogue that we hear in the film, spoken by the old woman of Escalot as she binds together bundles of sticks with the help of a little girl: “He whose footsteps one hears before seeing him will die within the year.” “Even if it’s his horse’s footsteps?” asks the girl. “Even if it’s his horse’s footsteps.”

In this brief exchange, we are introduced to the idea of predestination, thematically as well as concretely; the last words are immediately followed by the sound of a knight approaching on his horse, whom we subsequently see. We are also presented with the notion of sound preceding image — which becomes the central editing principle of the tournament sequence, and is much in use elsewhere. Finally, there is a forecast of the explicit ways in which the destinies of the horses are bound to those of the men who ride them: Lancelot’s return to Camaalot is intercut with shots of his horse responding to his fellow creatures in a nearby stall (evoking Balthazar’s encounter with the circus animals); the death of Lancelot’s horse in the final sequence immediately precedes his own; and throughout the film, much of the dialogue is punctuated by the sounds of horses, so that their presence or proximity is frequently felt even when they aren’t seen.

Bresson’s manner of infusing naturalistic detail with formal significance is particularly masterful in the marvelous use he makes of armor; in his hands, it serves as practical extensions of all but the second of the working strategies cited above. It functions as an additional layer of nonexpressiveness, increasing neutrality and uniformity in separate images and cloaking identities in many crucial scenes — the tournament as well as the forest battles. (Indeed, apart from the old woman and little girl, no positive identification of any of the characters becomes possible until Lancelot arrives in Camaalot, and lifts his visor to greet Gauvain.) When Gauvain is defending Lancelot to Artus against Mordred’s charges while the three are on horseback, each line of dialogue is preceded by the character lifting his visor to speak: again, a naturalistic detail, but one that heightens the antitheatrical basis of Bresson’s style precisely by playing on a “theatrical” device — each lifted visor serving as the equivalent of a raised curtain, which reveals only another blank surface.

The concentration on hands and feet that is a constant in Bresson’s work becomes all the more affecting here when it is set against the shiny surfaces of metal in other shots. Or consider the overall effect of contrast achieved between the suits of armor and the image of Guenièvre standing in her bath, which makes flesh seem at once more rarefied and vulnerable, more soft and graceful, more palpable and precious. The on- and offscreen rattle of the armor throughout the film reinforces this impression, at the same time that it isolates the more lifelike sounds coming from horses and men, and emphasizes their (minimal) expressiveness, thus investing Lancelot’s last word with a sensual impact it wouldn’t otherwise have.

Bresson has described himself both as a painter and as a metteur-en-ordre. Combining these notions, he establishes and mixes his sounds like colors on a palette and then places them “in order,” establishing relationships that are purely aural as well as visual-aural. The spare use of drum and bagpipe, the armor, horses’ footsteps, sounds of blood and water (including a rainstorm, glimpsed in one extraordinary fixed shot), a door rattling, birds calling, flags waving in the wind, a flurry of arrows whizzing through the air, and the crack of lances hitting shields are only a few of the essential ingredients. It is said that while working on the sound track, Bresson wanted to include at one point the sound of a horse chewing on his bit; having no recorded examples that were satisfactory, he wound up manufacturing the noise with his own teeth. It is a story that irresistibly brings to mind the methods of Tati — perhaps the only contemporary of Bresson who composes and organizes his sound tracks on a comparable level.

The extreme darkness of many of the forest scenes — in itself a source of great beauty — often helps to accentuate the function of sounds in guiding our attention, but the frequent expositional use of sound in brighter locations is equally striking. In the cottage of the old woman of Escalot, we first discover the presence of a fire burning in the hearth through the sound of its crackle. And in the astonishing tournament sequence, sound becomes the primary narrative force: the crowd is heard but remains virtually unseen, and we hear the collision of lances with armor in the first two encounters before we are permitted to see the outcomes.

Many critics have spoken of Bresson’s style as one that ideally eliminates the possibility of suspense —usually citing the title UN CONDAMNÉ À MORT S’EST ECHAPPÉ, which gives away the outcome of the plot, as crucial evidence. But as Hitchcock reminds us in his interview book with Truffaut, knowing the outcome of an event can often intensify suspense, and surely UN CONDAMNÉ À MORT frequently plays on our expectations to generate tension, even if the form of this tension is severely disciplined. And in the jousting tournament of LANCELOT, whether we know (through some acquaintance with the legend) the outcomes or not, we are being “directed” as rigorously as in any Hitchcock showpiece: there are few other action sequences in all cinema that create as much anticipation and excitement.

Finally, of course, there are the voices — neutral and uniform in their apparent lack of expressiveness, but presences charged with meaning and effect in relation to the overall complex of sound and silence, where the lack of overt emotion becomes a sounding brass against which the words themselves are able to resound. “Tu es vivant, et tu es là,” says Guenièvre to Lancelot, back from the Grail quest. “Rien, plus jamais, ne t’écartera de moi!” In the system of meanings established by Bresson, presence defines absence, life (“Tu es vivant“) defines death (“Guenièvre!“), a dark earth defines a bright sky, and love defines the renunciation of love — armor and flesh, sound and image, Lancelot and Guenièvre composing one another through diverse channels to form an indissoluble surface that speaks.

Notes

[1] Available in English translation as The Death of King Arthur, translated by James Cable (New York: Penguin Books, 1971).

[2] Robert Bresson, rev. ed. (Paris: Seghers, 1974).

[3] “The flatter an image is, the less it expresses, the more easily it is transformed in contact with other images.” “It is necessary for the images to have something in common, to participate in a kind of union.”

— Sight and Sound , Summer 1974