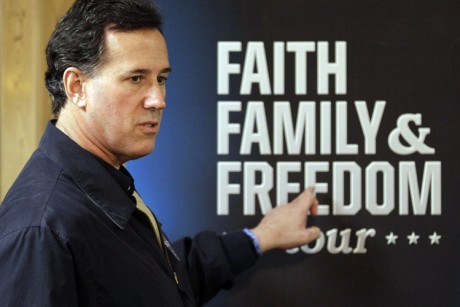

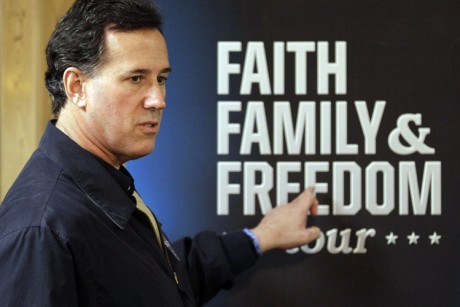

Russ Limbaugh on Rick Santorum (after explaining that Newt Gingrich and John Kerry were once on the same panel where they sort of agreed that global warming exists): “Nobody is innocent. Everybody is guilty on [sic] some transgression somewhere against conservatism. Except Santorum.”

Rick Santorum on Western Europeans (speaking to the conservative Pennsylvania Leadership Conference in 2006): “Those cultures are dying. People are dying. They’re being overrun from overseas…and they have no response. They have nothing to fight for. They have nothing to live for.”

Clearly, Rick Santorum can’t be guilty of any transgression against any European conservatives, secular or religious, responsive or otherwise. How could he be, because they don’t exist? Or at least have no reasons to live, or anything to fight for, anywhere. Or somewhere.

Thanks, Russ and Rick, for clarifying that we must be the only folks in the world who exist, or deserve to, or want to — at least one of those things, or maybe, if they can have their way, all three. [2/10/12]

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (March 1, 1992). — J.R.

Peter Bogdanovich directs Marty Kaplan’s adaptation of Michael Frayn’s highly successful stage farce about a director (Michael Caine) and a cast of hapless actors trying to whip a sex farce into shape. The transition from stage to screen may be bumpy in spots, but this movie is much funnier than Bogdanovich’s What’s Up, Doc?, and the long-take shooting style is executed with fluidity and precision. The basic idea is to hurtle us through three increasingly disastrous tryouts of the same first act, which might be loosely termed Desperate Dress Rehearsal in Des Moines, Actors in Personal Disarray Backstage in Miami Beach, and Props in Revolt in Cleveland; the fleetness of this raucous theme-and-variations form makes it easy to slide past the confusion of all the onstage and offstage intrigues. I can’t comment on the changes undergone by Frayn’s material, except to note that I find it hard to buy the closing artificial uplift, which seems to have been papered over the original’s very English sense of pathos and defeat. Ironically, after the warm and dense ensemble work of Texasville, Bogdanovich reverts here to the cold-blooded mechanics of choreographing one-trait characters, though the chilly class biases of his early urban comedies once again give way to something more egalitarian and balanced. Read more

Cowritten by Yehuda Safran (a lecturer in the philosophy of art with whom I was sharing a flat in Hamstead at the time), and published in the Winter 1974/75 issue of Sight and Sound. It seems fair to say that this review (from the 1974 London Film Festival) is in some ways more Yehuda’s than mine. Note: This film has more recently been called Part-Time Work of a Domestic Slave in some English-speaking countries. -– J.R.

‘Roswitha feels an enormous power within her,’ Alexander Kluge remarks offscreen at the outset of his latest feature, ‘and cinema teaches her that this power exists.’ The task of making the invisible visible is essentially the project of a director more concerned with social and political history than with film history, who seems to regard his work as a translation of ideas into sounds and images rather than the other way round. What matters is what the words and images ‘say’ and imply in relation to each other -– not their independent formal qualities, but their capacity of modify and explicate a complex experience.

What do Kluge’s opening words say and imply? That film is a means of translating potentiality into actuality, feeling into thought, experience into understanding –- the very problem that Roswitha Bronski (Alexandra Kluge, the director’s sister) is struggling to cope with over the film’s duration. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (September 1, 1990). — J.R.

One of the most surprising things about Peter Bogdanovich’s bittersweet, touching comedy sequel to The Last Picture Show (1971) — based, like its predecessor, on a Larry McMurtry novel — is that, far from being a trip down memory lane, it’s largely structured around historical amnesia. The hero walks with a limp and has grown estranged from his wife, and his former girlfriend has lost her husband and son, though the reasons and circumstances behind these and other essential facts go unmentioned: they’re buried somewhere in the forgotten past. The people we last saw in the small town of Anarene, Texas, are now 30 years older, and the only one mired in the past is Sonny (Timothy Bottoms), the town’s mayor, a self-confessed failure and something of a lunatic. His best friend Duane (Jeff Bridges), whose point of view shapes the action — he’s an adulterer who hasn’t slept with his wife Karla (Annie Potts) for some time, and whose main sexual competitor is his own son (William McNamara) — has struck it rich in oil and subsequently run himself millions of dollars into debt while Karla continues to buy condos for their children. Read more

A slightly different version of the Introduction to my 2004 collection, Essential Cinema: On the Necessity of Film Canons. — J.R.

Introduction

As the son and grandson of small-town exhibitors — a legacy explored in detail in my first book, Moving Places: A Life at the Movies (1980/1995) — I find it difficult to pinpoint with any exactitude when my film education started. But I can recall two pivotal early steps during my freshman year at New York University in 1961, when I was an English major still aspiring to become a professional novelist: taking the first and only film course I’ve ever had in my life and purchasing my first film magazine.

The course was an introductory survey taught by the late Haig Manoogian, who was serving as Martin Scorsese’s mentor in production courses around the same time. For me, it mainly afforded me my first opportunity to see The Birth of a Nation, The Last Laugh, and a few other film history staples; since I had no interest in making movies — or at this point in writing about them — I couldn’t work up much enthusiasm for such matters as “story values” that Manoogian tended to emphasize. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (October 28, 1988). — J.R.

Clint Eastwood’s ambitious and long-awaited biopic about the great Charlie Parker (Forest Whitaker), running 161 minutes, is the most serious, conscientious, and accomplished jazz biopic ever made, and almost certainly Eastwood’s best picture as well. The script (which accounts for much of the movie’s distinction) is by Joel Oliansky, and the costars include Diane Venora as Chan Parker, Michael Zelniker as Red Rodney, and Samuel E. Wright as Dizzy Gillespie. Alto player Lennie Niehaus is in charge of the music score, which has electronically isolated Parker’s solos from his original recordings and substituted contemporary sidemen (including Monty Alexander, Ray Brown, Walter Davis Jr., Jon Faddis, John Guerin, and others), mainly with acceptable results. The film is less sensitive than it might have been to Parker’s status as an avant-garde innovator and his brushes with racism, and one is only occasionally allowed to listen to his electrifying solos in their entirety, without interruptions or interference (as one was able to do more often with the music in Round Midnight), but the film’s grasp of the jazz world and Parker’s life is exemplary inmost other respects. The extreme darkness of the film, visually as well as conceptually, leaves a very haunting aftertaste. Read more

From AFI Education Newsletter (January-February 1982). Because of the length of this, I’ll be running it in two installments. — J.R.

Course File:

EXPERIMENTAL FILM:

FROM UN CHIEN ANDALOU TO CHANTAL AKERMAN (Part 2)

UNIT III: German and Soviet Experimentation in the Twenties

Part of the strategy of studying German and Soviet experimentation over roughly the same period is the striking contrast between these national film movements and their relationship to popular genres as well as their different themes and subjects. On the one hand, one finds the efforts of a Fritz Lang to experiment with the thriller format, and those of F.W. Murnau (and his scriptwriter Carl Mayer) to construct an essentially non-verbal visual language. On the other hand, one finds the relatively less script-bound experiments with montage and certain documentary principles provided by the Soviet filmmakers. An interesting topic to consider speculatively is the Soviet version of Lang’s first Dr. Mabuse film, which was re-edited by Eisenstein for Russian audiences.

Screenings:

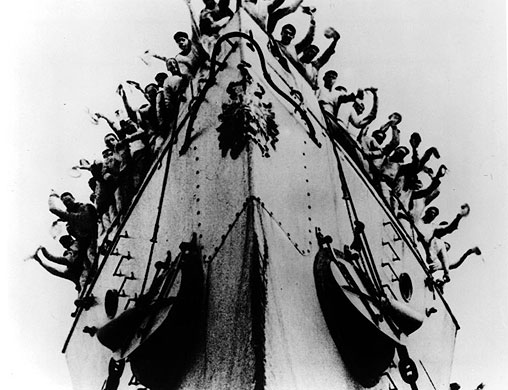

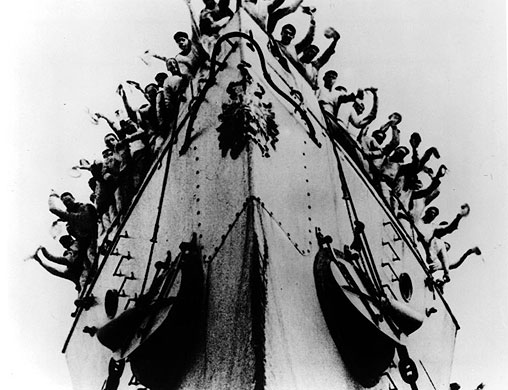

Bronenosets Potemkin (The Battleship Potemkin) (1925, 65 min.) Directed by Sergei Eisenstein — Perhaps the most famous of all experimental films, including some 1300 shots, Eisenstein’s classic is structured in five “acts.” Along with Strike, made the previous year, this is the most accessible of Eisenstein’s silent films, and might be contrasted with October (or significant portions thereof) in terms of the different principles of montage at work. Read more

From AFI Education Newsletter (January-February 1982). Because of the length of this, I’ll be running it in two installments. — J.R.

EXPERIMENTAL FILM:

FROM UN CHIEN ANDALOU TO CHANTAL AKERMAN (Part 1)

UNIT l: lntroduction

One distinct advantage to teaching a course in experimental film as opposed to avant-garde film is that it automatically gives one much more leeway in terms of screenings to be selected as well as overall teaching approaches. While “avant-garde cinema” can be regarded, by and large, as a distinct body of work with its own traditions, history and critical literature, “experimental film” is a rather more subjective and ambiguous category, and one that cuts across certain forms of commercial as well as avant-garde filmmaking. (There are many more references to various commercial forms of filmmaking, including Hollywood, in David Curtis’s Experimental Cinema, than there are in P. Adams Sitney’s Visionary Film: The American Avant-Garde.)

Consequently, any teacher setting out to plan a course in experimental rather than avant-garde cinema automatically has a greater amount of material to select from, and substantially more freedom in defining the scope and limits of his or her subject. By the same token, the demands placed on one’s imagination, creative input and organizational capacities might also be significantly greater. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (July 17, 1992). — J.R.

UNIVERSAL SOLDIER

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Roland Emmerich

Written by Richard Rothstein, Christopher Leitch, and Dean Devlin

With Jean-Claude Van Damme, Dolph Lundgren, Ally Walker, Ed O’Ross, Jerry Orbach, Leon Rippy, Tico Wells, and Ralph Moeller.

UNLAWFUL ENTRY

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Jonathan Kaplan

Written by Lewis Colick, George D. Putnam, and John Katchmer

With Kurt Russell, Ray Liotta, Madeleine Stowe, Roger E. Mosley, Ken Lerner, Deborah Offner, Carmen Argenziano, and Andy Romano.

A LEAGUE OF THEIR OWN

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Penny Marshall

Written by Lowell Ganz and Babaloo Mandel

With Geena Davis, Madonna, Lori Petty, Tom Hanks, Jon Lovitz, David Strathairn, Garry Marshall, Megan Cavanagh, and Rosie O’Donnell.

PRELUDE TO A KISS

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Norman Rene

Written by Craig Lucas

With Alec Baldwin, Meg Ryan, Sydney Walker, Ned Beatty, Patty Duke, Kathy Bates, and Richard Riehle.

Out of all the genres represented by this summer’s crop of movies, there are at least three that haven’t yet been officially recognized. There are sequels like Lethal Weapon 3 and Batman Returns whose true genres are not so much old-fashioned categories like police thriller and fantasy adventure as “this summer’s Lethal Weapon movie” and “this summer’s Batman movie.” Read more

From the Chicago Reader (November 1, 1989). — J.R.

An uncharacteristically nasty James Stewart plays an obsessive bounty hunter with Robert Ryan in tow in one of the very best Anthony Mann westerns — which means one of the very best westerns, period. This 1953 film has Janet Leigh in jeans, beautiful location shooting (and Technicolor cinematography) in the Rockies, and some of the most intense psychological warfare to be found in Mann’s angular and anguished oeuvre. With Ralph Meeker, Millard Mitchell, and a top-notch script by Sam Rolfe and Harold Jack Bloom. 91 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more