Cowritten by Yehuda Safran (a lecturer in the philosophy of art with whom I was sharing a flat in Hamstead at the time), and published in the Winter 1974/75 issue of Sight and Sound. It seems fair to say that this review (from the 1974 London Film Festival) is in some ways more Yehuda’s than mine. Note: This film has more recently been called Part-Time Work of a Domestic Slave in some English-speaking countries. -– J.R.

‘Roswitha feels an enormous power within her,’ Alexander Kluge remarks offscreen at the outset of his latest feature, ‘and cinema teaches her that this power exists.’ The task of making the invisible visible is essentially the project of a director more concerned with social and political history than with film history, who seems to regard his work as a translation of ideas into sounds and images rather than the other way round. What matters is what the words and images ‘say’ and imply in relation to each other -– not their independent formal qualities, but their capacity of modify and explicate a complex experience.

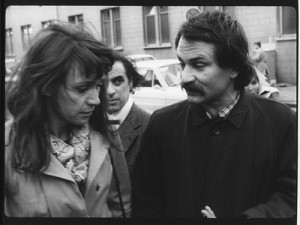

What do Kluge’s opening words say and imply? That film is a means of translating potentiality into actuality, feeling into thought, experience into understanding –- the very problem that Roswitha Bronski (Alexandra Kluge, the director’s sister) is struggling to cope with over the film’s duration. A 29-year-old Frankfurt housewife, she supports her children and husband Franz (a research chemist) by performing abortions, until a series of mishaps –- an unsuccessful operation, a rival abortionist reporting her activities to the police –- propels her into a life of political activism. Ostensibly reciting her lines as quotations in the Brechtian manner, she embarks on a semi-comic and quixotic quest to translate thoughts into actions while attempting to reconcile the separate compartments of her life. Generally as well as specifically, this leads to contradictions and collisions between society’s and the family’s separate modes of production, and an exposition of the options of an individual or the lack of them within each structure.

To sustain her family, she obliterates the possibilities of other families by removing fetuses from pregnant women; memorizing a song by Brecht with the help of her friend Sylvia, she invariably changes its functions and meanings. After Franz assumes the role of family breadwinner by going to work at the Beauchamp chemical factory, she and Sylvia try to express their outrage about workers’ conditions to a newspaper editor; unable to translate their concerns into the rhetoric of headlines, they come across as rather naïve –- the same way Roswitha is regarded at home by Franz.

Persisting, she protests about the sausages served in the factory cafeteria because they give the workers stomach ulcers. Later, she investigates the company’s secret plans to close the plant and transfer operations to Portugal –- even to the point of driving there, where she can see the new headquarters with her own eyes. But complications keep transforming our perspectives: the trip to Portugal accomplishes nothing (the management decides against the move independently of her actions); her political work isolates her further from Franz – who doesn’t know about it, and eventually loses his job as a direct consequence of her agitation. By the end of the film, her intricate cross-purposes have reached the point where she’s disseminating ulcers along with political statements to Beauchamp factory workers by wrapping her tracts around sausages, which she peddles from a vendor in steely defiance.

![[CM+Capture+1.jpg]](http://2.bp.blogspot.com/_oPjxy9iJ1nI/Syxr8nVhpfI/AAAAAAAACBE/P6QdqRRmvC0/s1600/CM%2BCapture%2B1.jpg)

It is worth noting that Kluge’s efforts at lucidity parallel Roswitha’s every step of the way. But his intelligence figures in the film as a process rather than as an object iof spectacle. (‘Find a place in the sun?’ asks one title. ‘Not easy, because once you’ve found it, the sun has set’), and ‘truth’ becomes a quest for meaning through diverse, divergent and even antithetical conditions rather than a concise set of conclusions or slogans.

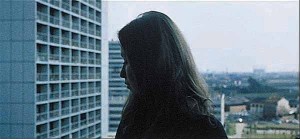

Yet Kluge persuades us that this absurdist terrain is precisely the one where politics happen. The apparent resemblance of his methods to Godard’s has frequently been noted; what remains interesting about it is how starkly it delineates the respective strengths and limitations of each in relation to art and politics. In 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her, Godard’s romantic, idealist politics generally involve seeing high-rise apartment complexes from above, magisterially, and drive him to create a new language that ultimately overtakes his political point of departure –- a housewife who lives in one of those complexes. ‘Language is the house that man lives in,’ she notes quite early in the film, and here as in La Chinoise an indelible purity of sound and image conspire to house a utopian vision. Kluge’s materialist grasp of politics involves seeing these images from below –- the viewpoint of the worker, not the visionary –- and adopting and adapting an available language (principally Godard’s) to pursue his meanings. Sounds and images become message-carriers rather than objects for contemplation, engendering a cognitive process which proceeds far beyond their appearances.

If we remember some of Kluge’s images, this is more because of their relation to other images and the ideas behind them than any other expressive capacities. The abortion sequence which occurs only a few minutes into the film is unforgettable, but its impact is ensured by Kluge’s manner of anticipating and reinforcing it. Outside the clinic, the camera moves up to a row of lighted windows behind a network of tree branches, and a drawing of curtains further suggests the Hollywood convention of dealing with a taboo from a comfortable distance; when we instantly cut to hands, surgical instruments and then the operation itself, the shock is as salutary as the shower murder in Psycho. Later, after Roswitha and Frnza buy one another comically inappropriate gifts –- a fishing rod and a gold wristwatch — she

accidentally drops the latter down a sink drain, and furtively tries to retrieve it. In one bold stroke, the abortion is recalled, with its sense of a lost possession (the foetus itself also winds up in a sink, under a clutter of instruments); ‘fishing’ for the watch brings to mind her equally gratuitous gift to Franz; and her concealment of the loss from him echoes her previous withholding of details about her abortionist career.

Kluge’s focus throughout is largely on these ‘invisible’ interrelations: a torch functions successively as an aid to Roswitha in repairing her car, a tool for smashing the body of another, and a trap when she emerges from a clandestine search through the factory to encounter the night watchman. Initially, her family is made visible through its presence; subsequently, its importance is registered through its absence: Roswitha deciding that ‘her family can’t live without her’ en route to Portugal, or collecting her children’s toys when she arrives home, late at night.

‘Give me a foothold outside the family,’ says one title, ‘and I’ll lift the world.’ Combining Archimedes’ definition of ‘work’ with an understanding of Marx and Engels, Kluge fuses physics, an observation on the nature of labour and a grasp of social forms in one elegant formula. Another quote, from Engels: ‘All families in capitalist society are modeled on the bourgeois prototype. This model is obsolete.’ Abortions simultaneously preserve and threaten the bourgeois family, but are carefully kept in a separate sphere; when Roswitha is expelled from this sphere, she becomes obsolete and ‘invisible’ — which drives her straight into politics. Yet for all the apparent futility of her attempts to tie the dangling threads of her life into a practical knot –- a problem that Kluge is much too wise (‘kluge’ in German) to propose utopian solutions for –- the increase in awareness is unquestionably a step forward in political consciousness. We sense an enormous power within Roswitha and her persistent aspirations; Kluge’s cinema teaches us that this power exists.

JONATHAN ROSENBAUM, YEDUDA SAFRAN