From the Chicago Reader (January 4, 2002). — J.R.

Souleymane Cissé’s extraordinarily beautiful and mesmerizing fantasy is set in the ancient Bambara culture of Mali (formerly French Sudan) long before it was invaded by Morocco in the 16th century. A young man (Issiaka Kane) sets out to discover the mysteries of nature (or komo, the science of the gods) with the help of his mother and uncle, but his jealous and spiteful father contrives to prevent him from deciphering the elements of the Bambara sacred rites and tries to kill him. Apart from creating a dense and exciting universe that should make George Lucas green with envy, Cissé has shot breathtaking images in Fujicolor and has accompanied his story with a spare, hypnotic, percussive score. Conceivably the greatest African film ever made, sublimely mixing the matter-of-fact with the uncanny, this wondrous work won the jury prize at the 1987 Cannes festival, and it provides an ideal introduction to a filmmaker who is, next to Ousmane Sembène, probably Africa’s greatest director. Not to be missed. 105 min. A new 35-millimeter print will be shown. Gene Siskel Film Center, 164 N. State, Friday, January 4, 6:15 and 8:15; Saturday, January 5, 4:15, 6:15, and 8:15; Sunday, January 6, 4:15 and 6:15; and Monday through Thursday, January 7 through 10, 6:15 and 8:15; 312-846-2800. Read more

The Film Center’s ongoing retrospective of the work of Italy’s greatest living filmmaker, Michelangelo Antonioni, offers two noteworthy programs this Friday night. First is perhaps the most unjustly neglected of Antonioni’s early features, Lady Without Camelias (La signora senza camelie, 1953), a caustic Cinderella story about a Milanese shop clerk (Lucia Bose) who briefly becomes a glamorous movie star. One of the cruelest and most accurate portraits of studio moviemaking and the Italian movie world that we have, it’s informed by a visually and emotionally complex mise en scene that juggles background with foreground elements in a choreographic style recalling Welles at times. Though it’s only Antonioni’s third feature, and it’s episodic structure necessitates a somewhat awkward expositional method, this is mature filmmaking that leaves an indelible aftertaste.

Then comes a program of shorts made between 1947 and 1953, mainly “apprentice” works, though no less impressive and commanding for all that; the only conventional and fairly forgettable one is the last in the program, The Villa of Monsters (1950)–to be shown, unlike the others, only with French and German subtitles. Perhaps the most significant stylistic trait to be found in most of the work here is the pan suddenly linking foreground with background, the animate with the inanimate. Read more

Written for Kino Lorber’s Blu-Ray of the film, released on November 10, 2015. — J.R

Alain Resnais (1922-2014) was the most experimental and adventurous of all the French New Wave directors, but he has rarely been recognized as such, perhaps because he stood apart from his (mainly younger) colleagues in other respects as well. Unlike Godard, Rivette, Truffaut, Chabrol, and Rohmer, he wasn’t a critic or a writer, although as a teenager during the German Occupation of France he was already serving as a mentor to their own critical mentor, André Bazin, by introducing him to silent cinema in general and Fritz Lang in particular. He also preceded them all as a director in the eight remarkable non-fiction shorts he made between 1948 and 1958, the first of which (Van Gogh) won him his only Oscar. Indeed, the moment one compares these innovative shorts to the early sketches of Godard, Rivette, et al., the clearer it becomes that Resnais was already a courageous radical, both formally and politically, long before such a position even occurred to his colleagues. And one could argue that he was also already a film critic and film historian on his own elected turf, namely sound and image, even if he didn’t exhibit his exquisite cinematic taste in writing. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (September 25, 1987). — J.R.

While it may not add up to anything very profound, this paranoid thriller is put together with so much craft and economy that a significant part of its pleasure is seeing how tightly and cleanly every sequence is hammered into place. Brian Dennehy is Dennis Meechum, an incorruptible police detective who doubles as a successful crime writer; James Woods is Cleve, a hit man who doubles as a corporate executive, and who wants Meechum to write a nonfiction best seller exposing his ruthless and respectable former boss — a philanthropist tycoon who has stealthily slaughtered his way to the top. Dennehy’s square and skeptical cop is an adroit reading of a dull part, but he makes a wonderful straight man for Woods’s fascinatingly creepy yet sensitive killer — modeled in part on Robert Walker’s Bruno Anthony in Strangers on a Train, with a comparable homoerotic tension between the two men. Tautly and cleverly scripted by Larry Cohen, crisply shot by Fred Murphy, and directed by John Flynn without a loose screw in sight, this is first-class action story telling, stripped to its essentials: no shot is held any longer than is needed to make its narrative point, and the streamlining makes for a bumpless ride. Read more

From Film Comment (May-June 1974). Apart from my responses here to Malle, Whale, and Fejos, I no longer identify with most of what I wrote here, over 41 years later. Much of this -– especially my reactions to Ferreri and The Great Garrick — was strongly influenced at the time by my friendship with the late Eduardo de Gregorio. — J.R.

The word is out that Marco Ferreri’s TOUCHE PAS LA FEMME BLANCHE (DON’T TOUCH THE WHITE WOMAN) isn’t making it at the box office. The notion of staging a semi-political, semi-nonsensical Western in Les Halles seems to be bewildering French audiences, even when they laugh, and neither the presence of Michel Piccoli, Marcello Mastroianni, Philippe Noiret, and Ugo Tognazzi, nor the singular glace of Catherine Deneuve as the white woman, appears to have turned the trick. Our local Philistine, Thomas Quinn Curtiss in the International Herald Tribune, was distinctly sourced by the experience: “The subject is certainly serviceable for caricature, but Ferreri’s hand is so clumsy that the result is rather a burlesque of the cow operas of his homeland…All is grotesque, but nothing is funny in this wild, tasteless travesty that consistently misses its targets.” When I mentioned liking the film to a French colleague on the phone, I can almost swear I heard an audible shudder creep across the lines. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (October 1, 1993). — J.R.

Director Tony Bill (My Bodyguard, Five Corners, Crazy People, Untamed Hearts) brings a lot of feeling and detail to this sort-of-true-life tale written by executive producer Patrick Duncan. It’s about a single mother (Kathy Bates) with no savings who leaves Los Angeles with her six kids for rural Idaho in 1962, and much of the family’s saga is very moving. (Duncan himself, who actually grew up with 11 siblings, corresponds to the oldest child and narrator here, played by teenager Edward Furlong.) Along the way the film loses some of its conviction; it winds up trying too hard and pushing some of its effects. Even so, the depiction of poverty has plenty of grit and flavor, and the cast — which also includes Soon-teck Oh and Tony Campisi — does a creditable job. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (May 1, 1991). — J.R.

Considering that the script for this 1990 movie (by the late Charles Williams and his wife Nora Tyson, adapted from Williams’s novel Hell Hath No Fury) was in development for about 30 years and that the film is Dennis Hopper’s worst as a director, this is still pretty enjoyable as a piece of campy sleaze — especially for the first half hour, before the storytelling starts to dawdle. There’s a score by John Lee Hooker and Miles Davis, who pursue waspy duets, and Hopper’s eye for color and composition is as sharp as ever. But even if one overlooks the noirish misogyny (no easy matter), the story is still an overheated hoot. Just when one hopes that the scumbag characters — including a footloose hustler (Don Johnson) who sidles into a job as a car salesman in a sleepy Texas town, his boss’s sexpot wife (Virginia Madsen), and a seedy, bemused banker (Jack Nance) — will develop beyond their cliches, they become even sillier. And the apparently innocent accountant (Jennifer Connelly) who becomes entangled in the morass isn’t any more believable. Some may view the film’s liabilities (e.g. the inexpressive Johnson filling the foreground like a block of wood) as assets and coast along with the steamy sex, but it’s still pretty slim pickings from the man who once made Out of the Blue. Read more

I’ve already blurbed this book, both on this site for its French edition and on Amazon for its e-book Kindle edition (where you can also read a couple of perceptive five-star reviews from other fans), so let me just reiterate here that if you haven’t yet checked this sucker out, you’ve got a lot of unhealthy fun awaiting you. [4/17/13] Read more

From the September 1, 1987 Chicago Reader. Criterion has released this film on a Blu-Ray with many extras. –J.R.

Try as he might, writer John Sayles has never been a natural filmmaker. But this sincere 1987 account of a coal miner strike and subsequent massacre in West Virginia in 1920 is so conscientiously detailed and so keenly felt and imagined — as well as attractively shot, by Haskell Wexler — that he deserves at the very least an A for effort. Simpleminded yet stirring, his depiction of a community of local whites, migrant blacks from the Deep South, and immigrant Italians gradually joining forces against the company bosses and their henchmen, under the leadership of a pacifist organizer, offers a bracing alternative to complacent right-wing as well as liberal claptrap. If Sayles’s bite were as lethal as his bark, he might have given this a harder edge and a stronger conclusion. But the performances are uniformly fine: Chris Cooper, Mary McDonnell, Kevin Tighe (perfect in dress and physiognomy, but strictly one-dimensional as scripted), James Earl Jones, and Sayles; the regional accents are especially well-handled. 133 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

This review of Other Voices, Other Rooms appeared in the February 13, 1998 issue of the Chicago Reader. I’m not positive that the second image I’ve used to represent Sokurov’s Oriental Elegy actually comes from that video and not from another Sokurov work, but it evokes my memory of that video so well that I hope I can be granted poetic license for this. — J.R.

Other Voices, Other Rooms

0 (worthless)

Directed by David Rocksavage

Written by Sara Flanigan and Rocksavage

With Lothaire Bluteau, Anna Thomson, David Speck, April Turner, and Frank Taylor.

By Jonathan Rosenbaum

I cannot tell a lie: my first exposure to two great tragic novels, Nathanael West’s Miss Lonelyhearts (1933) and William Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury (1929), was the dreadful Hollywood adaptations released during my teens, both of which had happy endings. As silly as these movies were — Vincent J. Donehue’s Lonelyhearts (1958) and Martin Ritt’s The Sound and the Fury (1959) — they piqued my interest in the original novels, and I discovered, among many other things, the blatant inadequacy of the movie versions.

The same thing could happen to a teenager attending the dreadful film adaptation of Truman Capote’s first published novel, Other Voices, Other Rooms (1948) — not a novel of the same caliber as West’s and Faulkner’s, though still a work of real distinction, from his best period — but the odds are slim. Read more

Mia Farrow on Spielberg and Riefenstahl

I’m almost two weeks late in hearing about this, but I’m assuming other latecomers will be interested as well in the op-ed piece published by Mia Farrow and her son Ronan in the March 28 issue of the Wall Street Journal. Titled “The Genocide Olympics,” the Farrows’ article attacks Steven Spielberg for his friendliness in agreeing to help stage the Olympics ceremonies in Beijing, thereby implicitly putting some kind of seal of approval on China’s complicity in the Darfur genocide, which the Farrows have recently been observing firsthand. “Is Mr. Spielberg, who in 1994 founded the Shoah Foundation to record the testimony of survivors of the holocaust, aware that China is bankrolling Darfur’s genocide?” they ask. And a bit later: “Does Mr. Spielberg really want to go down in history as the Leni Riefenstahl of the Beijing Games?”

Various web sites have been having a field day with this, on the right [2014: this link, at http://www.libertyfilmfestival.com/libertas, has subsequently been removed] as well as the left. The right, of course, is taking particular pleasure in drawing attention to the hypocrisy of a liberal like Spielberg.

Read more

Commissioned by the Chicago Reader in late September 2016. — J.R.

The eponymous New Jersey town proves to be a hotbed of poetry and art in this comedy from writer-director Jim Jarmusch, thanks to his beautifully loony conceit that all ordinary Americans are closet poets and artists of one kind or another (even if they don’t always know it). The bus-driver hero (Adam Driver), also named Paterson, writes poetry, and his Iranian wife (actress and rock musician Golshifteh Farahani) goes in for black-and-white domestic design; they know they’re artists and are completely smitten with one another, but their neighbors in a local bar seem less fortunate. Like many of Jarmusch’s best films, this keeps surprising us with its minimal, witty inflections, at once epic and small-scale, inspired in this case by the book-length poem Paterson by William Carlos Williams. (Jonathan Rosenbaum)

Read more

Read more

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8yr8hEyFYcg

The Portuguese title of this beautiful, wordless 15-minute documentary means “One Century of Power,” and the black and white footage comes from one of his earliest films, Hulha Branca (1932). [7/8/15]

Read more

Read more

A Critic’s Choice from the April 9, 1999 Chicago Reader. Seeing Luigi Zampa’s wonderful To Live in Peace (1947) yesterday, for the first time, at Il Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna, I discovered the same theme attached to an earlier and more “popular” war, expressed largely in comic and even farcical terms. — J.R.

Essential viewing. This documentary about a group of American and Vietnamese war veterans, many of them disabled, bicycling 1,200 miles from Hanoi to Ho Chi Minh City is many things at once — act of witness, account of a multicultural exchange, sports story, journalistic investigation, and mourning for the devastation of war. Ultimately it may be too many things to yield a cumulative effect, yet its scenes of former soldiers struggling with the meaning of the war are the most moving ones on the subject since Winter Soldier (a wartime agitprop film in which Vietnam veterans confessed their “war crimes”). The corporate sponsorship of the bicycle marathon adds many ironic layers, but the emotional encounters it permitted seem more important than anything else I’ve seen about our involvement in Vietnam. Coproduced by Chicago’s Kartemquin Films and directed by Jerry Blumenthal, Gordon Quinn, and Peter Gilbert (Hoop Dreams). Read more

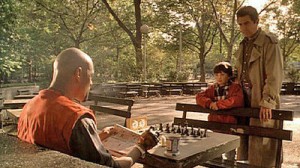

From the Chicago Reader (August 1, 1993). — J.R.

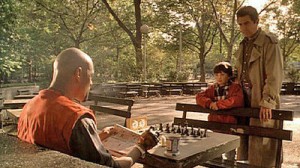

One of the craftiest and most satisfying pieces about gender politics to come along in ages (1993) — all the more crafty because audiences are encouraged to see it simply as a movie about a seven-year-old chess genius, based on Fred Waitzkin’s nonfiction book about his son Josh. Very well played (with Max Pomeranc especially good as Josh), shot (by Conrad Hall), and written and directed (by Steven Zaillian, who also scripted Schindler’s List), it gradually evolves into a kind of parable about how a gifted kid learns to choose his role models and choose what he needs from them. The part played by gender in all this is both subtle and complex, relating not only to chess strategy (e.g., when to bring your queen out) and the personality of Bobby Fischer, but also to the varying attitudes toward competition taken by his parents (Joe Mantegna and Joan Allen) and two teachers (Laurence Fishburne and Ben Kingsley). It makes for a good old-fashioned inspirational story, absorbing and pointed. (JR)

Read more

Read more