Published by Chicago’s a cappella press in 2000. The jacket reproduced below, which I prefer, belongs to the English edition published by Wallflower Press in 2002; the full title is Movie Wars: How Hollywood and the Media Limit What Films We Can See. — J.R.

To refer to a producer’s oeuvre is, at least to me, as ignorant as to refer to the oeuvre of a stockbroker.

— David Mamet

There are a lot of complaints these days about the declining quality of movie fare, and the worsening taste of the public is typically asked to shoulder a good part of the blame.

Other causes are cited as well. The collapse of the old studio system meant the loss of studio heads who lent their distinctive stamp to each of their pictures — often vulgar and overblown, to be sure, but also personal and engaged — to be replaced largely by cost accountants and corporate executives with little flair, imagination, or passion. The exponential growth of video has made home viewing more popular than theatrical moviegoing and has therefore helped to diminish everyone’s sense of what a movie is, so that the size and definition of the image, a clear sense of its borders, the quality and direction of light, and the notions of film as community event, theatrical experience, or “something special,” have all suffered terrible losses. More simply and immediately, there’s the preference for loud explosions and frenetic comic-book action over drama and character, escalating violence over tenderness, torrents of profanity over well-crafted dialogue.

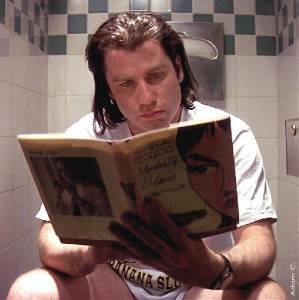

But most of the blame falls on the overall coarsening of the audience. According to conventional wisdom, most movies are targeted to the teen and preteen market; the decreased literacy of the filmgoing public rules out most subtitled movies; and there is an overall dumbing down of American movies, with a notable increase in anti-intellectualism, according to essayist Phillip Lopate, who cites Pulp Fiction, Ed Wood, Natural Born Killers, Bullets over Broadway, and Barton Fink (1), edgy American independent fare. Many industry commentators are quick to add that as the public grows increasingly apathetic, apolitical, jaded, and cynical, movies designed for their delectation would naturally follow suit.

Let’s concede that there’s some measure of truth in all these assertions — as there is in most assertions, at least if one bothers to look for it. But focusing on the last statement for a moment, might not the industry commentators have their cause and effect reversed? Couldn’t the movies, rather than their designated spectators, be spearheading as well as defining this decline — or don’t they need to share at least part of the responsibility for this overall dumbing down? Given the uncritical promotion of the major studio releases, one might even posit that the press, in order to justify its own priorities, maintains a vested interest in viewing the audience as brain-dead. After all, if it showered most of its free publicity on more thoughtful and interesting movies, it would run the risk of being branded elitist. How much easier it becomes to wallow in the slime if you and your editor or producer are persuaded that it’s the audience’s natural habitat — that the audience, not the press working in collaboration with the studios’ massive publicity departments, calls all the shots.

Furthermore, or so the producers tell us, the highly sophisticated forms of market research and testing that shape major releases at every stage in their development, from initial treatments to previews to final ads, scientifically prove that the studios are correct in their low estimation of the public taste. This is clearly the surest indication of what the audience actually wants, so how can the producers be faulted for catering to their preferences?

I suggest that this line of reasoning is even more stupid, self-serving, and self-deluded than the worst of these movies, deriving from a set of interlocking rationalizations that extend all the way from studio heads to reviewers. Since the majority of movies made according to these “scientific” principles bomb, it wouldn’t even be worth considering if it didn’t provide one of the essential rationales for making so many bad movies, as well as one of the most dubious recipes for moviemaking and profit making alike.

As a bracing rejoinder to this set of assumptions, try the following on for size:

It seems legitimate to wonder how men of the perspicacity which has distinguished some of the best work in market research could have failed to realize from the beginning that most of their research practices were not adaptable to the cultural field. The very attempt to adapt them to that field was virtually certain to cause damage.

Obviously, the premise of a stable audience with reasonably permanent and objectively verifiable needs simply does not hold in the cultural field. Transplanted from economics, this premise becomes an obvious interference with the free play of human intelligence. To say that men would always need warm clothing in cold weather obviously was a statement of fact; but to say that men would always need soap operas in America was just as obviously a plain insult. Yet the pollsters, straightfaced and single-minded, proceeded to ram their hypothesis down the public’s throat; the public, unaware of what was happening, had barely time to gag.

What was this hypothesis and how did it affect the public’s mental health? Adapted from mercantile economics to a field where mercantilism does not apply, the theory assumed a shallow, slothful, and unchangeable crowd, forever doomed to frustration and thus forever dependent on the wish fulfillment of certain minimum needs — sex, glamor, adventure, wealth, power, and the rest of them. The whole range of subtleties which make up the pattern of civilized behavior was not only rejected as being beyond the grasp of the audience — it was dismissed as irrelevant to their real desires.

Ernest Borneman’s commonsense dismissal of the basic assumptions of the American film industry in “The Public Opinion Myth” appeared in the July 1947 issue of Harper’s magazine.(2) But give or take a couple of sexist coinages that are standard for that period, I don’t see how it could be improved much today. Whether it can be absorbed and heeded is of course another matter, but if it could be, a revolution every bit as far-reaching as feminism would take place. Why it should be heeded — and what might start to happen if even a few of its simple observations were put into practice — is the subject of this book.

Why it’s unlikely to be heeded is simply a matter of economics: even by 1947, the industry founded on the public opinion myth was already too vast and too solidly in place to contemplate the prospect of dismantling it. If one compares it to this country’s military-industrial complex — which was getting established over the same period, justified by fears of the encroaching Communist menace — one might just as well hypothesize that once those fears had finally evaporated or died of old age, the massive military budget that had consumed so many of this country’s resources might be redirected to peacetime uses. The fact that it hasn’t been and won’t be seems every bit as unalterable as the public opinion myth, regardless of whether either rationale can be defended, because too many vested interests are committed to keeping these systems in place.

These interests are bolstered by a series of countermyths — chiefly the preservation and protection of “the free world” to justify the military-industrial complex, and “giving the public what it wants” to justify what might be called the media-industrial complex. And in the spirit of Noam Chomsky interrogating and critiquing just what we mean — and what we often don’t mean — when we speak of “the free world,” I’d like to talk about precisely what we mean and don’t mean when we speak of “giving the public what it wants” in relation to movies.

Though the implication of this introduction’s title is that the audience is sometimes right, I’m not really in a position to declare whether the audience is right or wrong about anything. Properly speaking, the audience is so many things, all of them overlapping and most of them scarcely known, that assigning it a label in advance effectively means ruling it out of discussion — which market research usually does. So my challenge is offered in a spirit of Hegelian antithesis to a thesis (the audience is to blame) that has riddled the film world to disastrous effect for much too long; hopefully, out of the synthesis might grow a more measured approach to something that no one — least of all market researchers — knows much about. And one extra advantage of my antithesis is that it opens up possibilities about what movies and audiences might be; the prevailing thesis can only close them down by ratifying policies that have already turned most of our movie culture to mush.

***

I strongly suspect that any studio publicist or production executive who read Borneman’s article today would maintain that movie market research was still in its infancy in 1947, that the nature of both the audience and the film industry has radically changed since then, and that even if Borneman’s argument once had some validity, it can no longer be applied to the contemporary realities of developing, making, testing, revising, publicizing, distributing, and exhibiting movies. Not only has the market research industry become more sophisticated, but the audience has undergone profound changes,temperamentally as well as demographically: it’s more demanding about some things (such as the quality of special effects) and less demanding about others (such as plots that make sense); it’s much younger; moreover, the video revolution has transformed everything having to do with movies. Today’s markets are defined differently because people attend movies as special events rather than as an everyday activity, the older segments of the audience tend to stay at home, and so on.

All these things are certainly true, but I can’t see how they alter the basic thrust of Borneman’s charge. Then and now, the operations of the media-industrial complex have been predicated on certain highly questionable assumptions about the audience, and charting box-office grosses to “prove” those assumptions is merely indulging in a self-serving form of circular reasoning. The bottom line is always the same: the audience is ultimately to blame for what it winds up seeing. We are told that this is the downside of democracy—we can’t always expect to like what the mass public endorses—a sentiment that can only provoke me into citing Borneman again:

Does the whole process of audience testing . . . really qualify as a democratic

process?Does it not resemble an election in which only one candidate has

been introduced to the electorate? Have we ever been given a freely

available standard of comparison between the pollsters’ “control card”

and its best alternative? If the difference between any two alternatives

is so negligible as to defeat judgment, have we, the public, truly

returned a valid opinion? And, finally, have the pollsters ever provided

us with the aesthetic training which would have enabled us to make a

reasonable decision?

Let’s translate these skeptical questions into a few practical

applications pertaining to the nineties. The December 17, 1993

Wall Street Journal carried a story headlined, “Film Flam Movie-

Research Kingpin Is Accused by Former Employees of Selling

Manipulated Data.” The story reported that about two dozen

former employees of National Research Group, Inc., which

handled most Hollywood test marketing, stated that their data

were sometimes doctored to conform to what their paying

clients asked for. These former employees ranged

“from hourly workers to senior officials” and mostly included

people who had left the company voluntarily. All the examples

given in the story (e.g., L.A. Story; The Godfather, Part III;

Teen Wolf) involved boosting a movie’s score, but one

could easily surmise that the reverse could have happened

on occasion whenthe studio for one reason or other wanted

a movie to fail—which actually happens more often than most

moviegoers realize. Before dumping Peter Bogdanovich’s

The Thing Called Love, for instance — a film about country-

western music hopefuls in Nashville, all of them played by

nonmusicians such as River Phoenix, Samantha Mathis, and

Sandra Bullock — Paramount test-marketed it by showing it

to country-western music fans, a move that seems about as

logical as previewing One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest in a

mental institution. This may not constitute “doctoring” test

results in the usual sense, but it certainly sounds a lot

like predetermining the outcome.

As a result of this Wall Street Journal story, National Research Group, Inc.

lost most or all of its Hollywood clients, and I’ve been told that its

successors have proceeded more cautiously. One might think that such

a revelation would cast doubts among reviewers and other industry

commentators on an already highly dubious practice, but no

such reflection or soul-searching ever took place. The industry needs

its self-fulfilling prophecies too badly to tolerate skeptics, and, as I hope

to show in this book, most film reviewers are hardly independent of

either studio interests or their alibis.

Writer-director James L. Brooks, who received most of his training

in TV sitcoms, is a talented filmmaker who believes so religiously in test

marketing that he seems fully willing to compromise his own work to

the point of unintelligibility in order to conform to its supposedly exacting

standards. This curious devotion to the mythology of market research

as an exact science was demonstrated most cripplingly in the fate of

his 1993 musical about contemporary Hollywood filmmaking,

appropriately named I’ll Do Anything. This movie was eventually

released in 1994 as a nonmusical after a series of test screenings

gradually persuaded Brooks to remove all of the movie’s musical numbers.

As a reductio ad absurdum of the perils of test marketing, I’ll Do Anything

should be seen by everyone in its musical and nonmusical versions, but

of course it won’t be, because seeing how much better it was before all

the meddling took place exposes the patent absurdity of the process.

So I’m afraid you’ll have to take my word for it: having had the

opportunity to see I’ll Do Anything as a musical, I can report that it was

immeasurably better in that form — eccentric and adventurous, to be

sure, but also dramatically and emotionally coherent.(3) The fact that the

movie bombed at the box office as a nonmusical doesn’t of course

mean that it would have scored commercially in its original form, but

considering that it had an artistic logic and integrity, surely it had a

chance of finding an audience if the studio had known how to market

it. (Ironically, part of the movie’s plot is directly concerned with test

marketing.) By the same token, it seems impossible to imagine how the

release version could have found an audience under any circumstances

because its emotional and dramatic raison d’être had been removed;

following the biblical injunction, “And if thy right eye offend thee,

pluck it out,” Brooks wound up eliminating so much of his original

conception that what remained was meaningless.

If test marketing was used exclusively to determine how certain pictures

could best be marketed and advertised, I would be inclined to consider

it defensible on those grounds; clearly studios have to determine what

segments of the audience a movie is most likely to appeal to, and to

represent that movie in advertising according to their discoveries. In

some cases, I might even defend the use of preview screenings to

determine whether certain pictures could turn a profit and therefore

whether they should be released. And I would agree that some directors,

especially directors of comedy, can benefit from previewing their rough

cuts to see when and how they get laughs before making their final cuts.

But using test marketing to impose last-minute changes on movies

seems much harder to justify, especially because it assumes that an

audience is qualified to make decisions of this kind. Of course we

wouldn’t dream of policing the writing of novels or the composing of

symphonies in this fashion. And if knowledge and expertise are necessary

to arrive at intelligent decisions, it’s hard to defend the idea of spectators

without these qualifications determining the shape and effect of

theatrical features.

Test marketing assumes that an audience confronted with something

new will arrive at a permanent verdict immediately after seeing it. But

our experience of movies—apart from the most routine fare—seldom

works that way. Our expectations play a considerable role in

determining our first reactions, and once we get past them all sorts of

delayed responses become possible; a day or a week or a month later,

what initially made us querulous might win us over completely. The

film industry factors out responses of this kind — responses that suggest

we’re capable of learning and growing — thus denying our capacity to

change before we can catch our breaths. Determining that a film’s

success or failure has to register instantaneously, the studio then becomes

locked into a treadmill of other assumptions that degrade the audience

even further.

Let’s consider another contemporary application of Borneman’s remarks.

The mantra that Americans hate subtitles — periodically brought forth to

explain why so few foreign-language films are distributed in the United

States — conveniently neglects such facts as (a) most Americans have

never even seen a subtitled foreign-language film, and (b) few if any

spectators have complained about the extensive use of subtitles in

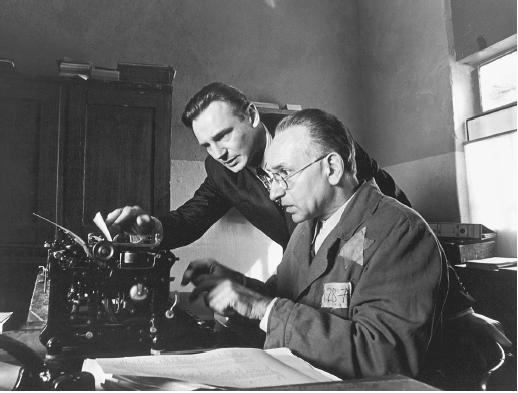

Dances with Wolves or Schindler’s List, or stayed away from

either of these movies as a consequence. It’s difficult to understand how

Americans can hate something they’ve never experienced — or have

experienced only in a situation when they didn’t consider it a problem.

A more accurate mantra might be, “Americans hate subtitles — except

when they don’t.” Similarly, if one bears in mind both the crippling

refusal of most producers to invest in black-and-white pictures and the

extensive use of black-and-white videos on MTV, one might hazard the

statement, “Teenagers hate to watch anything in black-and-white —

except when they don’t.” In other words, the audience is always to

blame, except for when it no longer makes any sense to blame them,

at which point the operative premises are forgotten. The alternate

possibility, which I explore in this book, is that we aren’t seeing certain

things because the decision makers are narrow-minded simpletons

who want to cover their own asses — interested only in short-term

investments and armed mainly with various forms of pseudoscience —

and it becomes the standard business of the press, critics included, to

ratify these practices while ignoring all other options.

It might of course be countered that Dances with Wolves, Schindler’s

List, and most black-and-white music videos that American audiences

see are American products, so that audiences are really objecting to (a)

foreign-language films from other countries and (b) black-and-white

features. But who says they’re objecting, and what do these alleged

objections actually mean? Black-and-white features started to become

almost impossible to finance once TV pollsters concluded that teenagers

tend to shift channels whenever they chance upon one. Even though a

significant number of the few recent black-and-white American movies

actually turn a profit — Pi is one example — film labs rarely manufacture

black-and-white film stock any longer, and those that do charge more

for it than for color stock. If this represents democracy in action, then

film audiences of the thirties, forties, fifties, and sixties who had a choice

about whether to see movies in color or in black-and-white were more

democratically empowered than audiences are today. But this has

nothing to do with democracy and a great deal to do with ill-conceived,

short-range business investments. In a witty and clarifying essay about

movie colorization, Stuart Klawans provides an interesting complement

to some of Borneman’s observations made almost half a century earlier:

It is certainly possible, though more difficult to prove than the executives

claim, that people prefer to watch television in color. The issue, though, is

not the public’s taste. It’s the way some executives, those with enough

power to dominate their markets, decide in advance what people want,

then justify their decision by noting that people have indeed bought the

only available products. With entertainment, moreover, as with drugs, the

product eventually creates a demand for itself. The public may be expected

to want colorization once the marketers have habituated them to it.(4)

Distinguishing between culture, education, and advertising has

never been more problematic. When Disney holds all-day “seminars”

about Native American culture and animation techniques for grade

school children in shopping malls as part of its campaign to promote

Pocahontas, the point at which advertising ends and education begins

(or vice versa) is difficult to pinpoint. And when teachers welcome such

assistance, how far are we from the prospect of Disney being asked to

take over public education? Similarly, when university film professors–

who have already agreed, in most cases for budgetary reasons, to

show videos instead of actual prints—restrict the films they show to

English-language works because “that’s what the students want,”

they’re capitulating to the same process.

But, as Borneman rightly asks, how can the public know what it

wants if it doesn’t know its choices? If someone dying of thirst is offered

a choice between liquid soap and shoe polish, can the selection honestly

be equated with what he or she “wants”? Babies don’t like to be

toilet trained either. And the studios not only treat the audience like

babies, but also never even consider toilet training.

Getting used to subtitles takes time and experience, and if the

larger distributors were thinking more in terms of long-term

investments, showing more subtitled pictures wouldn’t seem nearly as

risky. But as long as business thinking remains short-term, it’s much

easier to justify one’s business decisions tautologically and blame the

audience. It calls to mind the joke about the Florida orange juice stand

that offers “all the orange juice you can drink for a dollar,” only to inform

its customers after they’ve consumed a single thimble-sized glass of juice,

“That’s all the orange juice you can drink for a dollar.” From a certain

point of view, orange juice and cinema vendors have every right to

adopt this policy if they conclude that their customers are too stupid to

know they’re being fleeced. But can we celebrate such a policy as

consumers if all the cinema we can see for seven or eight or nine dollars is

radically restricted to what other people want us to see, not what we

want to see? This glib acceptance of the vendors’ position is part and

parcel of the isolationism that has crippled this country culturally over

the past few decades, and whether this isolationism is as necessary to

our souls and our economy as our tastemakers like to pretend is a

question that can’t be raised often enough.

The MPAA is another way the industry and its propaganda

machine routinely mask their operations. The usual deference with

which the media regards this organization hardly qualifies as a critically

weighted assessment; though critics grumble about some of its

judgments, they regard it more as a fact of life than a lobby with special

interests. (“I stopped taking the Motion Picture Association of America

Rating Board seriously,” wrote Anthony Lane in the April 5, 1999 issue

of The New Yorker, “when it demanded the removal, from a trailer for

Six Degrees of Separation, of a glimpse of the naked Adam on the ceiling

of the Sistine Chapel”; but such curt dismissals are few and far

between.) In fact, the way most people defer to the movie ratings system

implies that it’s an impartial means of conveying information and about

their suitability to separate age groups as a result. Though I doubt that

many would regard the MPAA as a government-run organization,

the authority of its judgments is often given the sort of sanction

accorded to the Food and Drug Administration, which we mentally

translate into an official stamp. That the MPAA is in fact operated

and regulated by the film industry is less often acknowledged; though

it’s not exactly a secret, the implications of this control are seldom

explored in depth. So the MPAA’s lenient treatment of studio releases

and severe treatment of independent releases — a double standard that

is taken for granted by industry insiders — is unlikely to be noted by

moviegoers, many of whom, thanks to careful industry training

fostered by name-brand associations, already share the same prejudicial

bias.

The obfuscation goes further if one considers the deceptiveness of

some of the brand names themselves. We all know that a Disney movie

is wholesome and a Quentin Tarantino movie is funky, right? Wrong,

because all of Tarantino’s movies to date have been released by

Miramax, a company that belongs to Disney. “Disney” includes

Touchstone, Hollywood, and Miramax, which allows it to work both sides of

the street —deceptively maintaining all the brand-name associations of

Disney on the one hand, and, on the other, obscuring its seedier enterprises

under different logos. And when it comes to Tarantino, other ideological

con games can be perpetrated as extensions of this cosmetic

camouflage. It’s easier to call Tarantino an independent filmmaker if

he makes his movies for a supposedly independent company like Miramax;

and it’s perfectly true that Miramax operates in relative independence

from its parent company, Disney. But just because Tarantino is

answerable to Harvey Weinstein at Miramax rather than to a suit at

Disney doesn’t mean that he has autonomy.

My idea of an independent filmmaker is someone who has final

control over his or her work, and Tarantino has never enjoyed this

freedom. Jim Jarmusch and Rob Tregenza, who have final cut on all their

own features and even own all their negatives, obviously qualify, but in

recent years it has been Tarantino and not either of them who has been

celebrated as an American independent —a gross misconception that

will continue to prevail as long as the studio’s shell-game persists.

Let’s consider another consequence of the studio propaganda

machine. A widespread controversy surrounding the 1999 Academy

Awards — only marginally apparent in the broadcast of the ceremony

itself, but the focus of a great deal of debate in the media over the

preceding weeks—was the granting and presentation of a Lifetime

Achievement Award to Elia Kazan. The issue at stake was not whether

his work as a film director warranted such an honor, although one could

certainly question the usual privileging of such features as Gentleman’s

Agreement, On the Waterfront, and Splendor in the Grass as his major

achievements over Panic in the Streets, Baby Doll, and Wild River. The

issue, rather, was whether Kazan, having named many of his former

colleagues for the House Un-American Activities Committee, should have

been forgiven. Admittedly, a good many other prominent people in the film

industry ratted on their coworkers in order to protect and sometimes boost

their own careers. But Kazan was in a strong enough position at the time to have

defied this committee without taking the same sort of risks as such fellow

directors as John Berry, Jules Dassin, Cy Endfield, Joseph Losey, and

Abraham Polonsky, all of whom refused to give names and had to suffer

for the remainder of their careers as a consequence. (The first four of

these, in fact, continued to work only by becoming European expatriates;

and in the cases of Endfield and Losey, due to threats from the American

projectionists’ union, they initially were able to work abroad only

secretly, assigning part of their salaries to others who agreed to serve as

“fronts.”) Moreover, Kazan went much further than those directors who

eventually buckled under pressure, such as Edward Dymtryk and Robert

Rossen, by offering scant resistance to HUAC; he even took out an ad in

The New York Times defending his own behavior and never subsequently

apologized or expressed any serious misgivings. According to this argument,

Kazan was not only cooperative with the Hollywood blacklist, he was

complicitous, and he was rewarded for his behavior with a lucrative

studio contract. For many if not all members of the Hollywood left,

honoring such an individual even four decades later was an unconscionable

act — perhaps even comparable to Ronald Reagan’s notorious Bitburg

speech that forgave the atrocities of Nazi soldiers.

I could agree with many of the people who protested the award, especially

those whose lives had been damaged by the blacklist. But I continue to

find inexplicable why Kazan was judged so harshly when the

perpetrators of the blacklist — the studio heads who refused to hire

blacklisted individuals — got off with a clean bill of health. Even if all

these moguls are dead, the industry often granted them accolades and tributes

when they were still alive, and to the best of my knowledge, not a word

of protest was heard against their honors because of their behavior during

the blacklist. These moguls, after all, were less the facilitators or the

patsies of the blacklist than they were the blacklisters themselves.

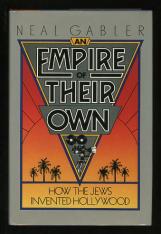

Moreover, most of them were Jewish, and one of the few who wasn’t, Darryl

F. Zanuck, was an avowed liberal. As Neal Gabler’s book An Empire of

Their Own: How the Jews Invented Hollywood demonstrates, these

moguls’ creation of the American Dream through their studio pictures

was largely an act of ethnic disavowal, which makes their collective

behavior even more odious. (According to Gabler, Hollywood’s dream

image of the Good Life grew out of the attempts of Adolph Zukor, Carl

Laemmle, Louis B. Mayer, the Warner brothers, and Harry Cohn to

escape from their European Jewish roots. Because a good many of the

blacklist victims were also Jewish, their scapegoating by the studios

functioned, in Gabler’s analysis, as a kind of Jewish anti-Semitism —

Jews throwing other Jews to the wolves as an unconscious act of self-

protection.)

So even the protest against Kazan’s honor implicitly kowtowed to

industry priorities, allowing the major culprits of the blacklist to go

unchallenged. It was entirely in keeping with Richard Dreyfuss’s

presentation of an Irving Thalberg Award to Steven Spielberg at an Oscar

ceremony in the early eighties, when Dreyfuss praised Thalberg’s

“courage” in defying Erich von Stroheim — that is, his courage in slashing

Stroheim’s two greatest films, Foolish Wives and Greed, to pieces

and making sure that all the deleted material was destroyed afterward.

The odds of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences ever

applauding the courage of a Stroheim, by contrast, are about as remote

as their ever bestowing similar honors on the courage of blacklisted

workers who refused to cave in under industry pressures.

***

Against the claims of our cultural commissars that they’re merely giving

the public “what they want,” let’s consider why newspapers, magazines,

and entertainment news on television list the ten top-grossing movies

every week, often with the grosses listed alongside them. It’s a fashion

supposedly dictated by public interest, yet for roughly the first eight

decades of this century, there was little evidence that such interest

existed, even in embryo. If a newspaper in the thirties, forties, fifties,

sixties, or even seventies had started to list the ten top grossers every

week, its readers would have supposed that the editor had rocks in his

head. So why, then, did the readers of the eighties suddenly start to

become interested in facts and figures that formerly had captured the

interest only of people working in the industry? Why, after all, should

anyone care how much money a particular picture makes? Wouldn’t

we find it peculiar if newspapers routinely listed the ten top-selling soft

drinks or fast-food outlets or cars every week, complete with a rundown

of the gross figures taken in by each product?

The simple reason is that this interest was cultivated, like so much

else in this culture that goes under the guise of spontaneous

combustion. If it hadn’t been promoted in the first place by publications

such as Premiere, it probably wouldn’t have caught on in other media

venues. And if it was possible for a magazine like Premiere to promote

such an interest, why wouldn’t it be possible for Premiere or another

magazine to cultivate an interest in foreign language films?

If this hypothesis sounds far-fetched, consider the career of one of

the inventors of public relations, Edward L. Bernays, an American

nephew of Sigmund Freud. The same man who convinced the

American people, at the behest of the American Tobacco Company, that

women smoking in public was an act of female liberation, previously

used the same promotional techniques to successfully sell first the

Russian Ballet and then Enrico Caruso to a recalcitrant American public.

Larry Tye, in his recent biography The Father of Spin: Edward L.

Bernays and The Birth of Public Relations, charts the applications of

Bernays’s techniques still further: “The selling of America on the Persian

Gulf War was a public relations triumph . . . crafted by one of America’s

biggest public relations firms, Hill and Knowlton, in a campaign

bought and paid for by rich Kuwaitis who were Saddam [Hussein]’s

archenemies.” (5) One of my main points in the chapters that follow is

that there are much better movies for us to see than the Persian Gulf

War, if only we can discover how to find them.

***

In the summer of 1998, after striking a deal with Blockbuster Video,

CBS, TNT, Turner Classic Movies, and the home-video divisions of

thirteen film studios, the American Film Institute made a last-ditch

effort to raise some money to replace its shrinking state grants. It

created a ludicrous list of the “One Hundred Greatest American

Movies” — a short-sighted hit parade of recent box office champs and

forgettable Oscar winners larded with a few familiar classics. (For a

further discussion of this list, as well as an alternative selection, see

Chapter Five.) The public outcry was immediate and palpable, but this was

far from the first time that marketers and publicists supplanted the roles

of historians and critics. If the press hadn’t already been nodding at the

switch, such an unwitting insult to the intelligence of the public might

not have ever been conceived — much less delivered in the form of a

summer-long media blitz — because the credibility of such ventures has

always depended on the willingness of the press to grant them space

and respect. As I hope to demonstrate, the press’s abnegation of any

commitment to the public beyond a servicing of privileged business

interests has allowed such crass undertakings to dominate what

remains of American film culture.

On the other hand, the AFI had also been given a clean playing

field by most of film academia, which has avoided promulgating overt

film canons since the early eighties. How this curious turn of events

came about is one of the issues I’ll be discussing in Chapter Four, but

for the moment, without proposing any conspiracy theories, I’d like

to suggest that the passive behavior of this country’s critical community

inside both academia and the mainstream press has paved the

way for an unblocked proliferation of marketing schemes by an

industry that knows only what it has to sell — not why it’s worth selling

or why anything else might be worth selling in its place. Significantly,

while a good version of The Birth of a Nation — the only silent film

on the list apart from Charlie Chaplin — is available on video from

a company called Kino, the AFI chose to “recommend” (i.e.,

advertise) an abominable, much reduced rerelease version offered by

one of the thirteen studios.

***

To pursue my argument in this book, I’ve loosely organized my discussion

around a few overlapping topics and examples selected to illustrate as well

as debunk some of the fallacies that currently govern what passes for

film culture in this country: the matching notions that the audience is to

blame for what it sees and that producers and studio heads are relatively

blameless (which I’ve already begun to address in this introduction);

the myth that declares that the cinema is over (which paradoxically

winds up endorsing and perpetuating the status quo); two chapters

on the vagaries of distribution, exhibition, promotion, and criticism;

a discussion of the contrasting American critical receptions of

Small Soldiers and Saving Private Ryan; “Communications

Problems and Canons” (which addresses both the issue of

information flow and the frequent failure of academic film study

to engage meaningfully with American film culture as

a whole); the assumptions and implications underlying the

American Film Institute’s unspeakable list of the “hundred greatest

American movies”; American isolationism as a form of economic

and cultural control; and then a discussion of the ways in which

an American national cinema may no longer exist (with Starship

Troopers used as an example of where some of the problems lie).

The last three chapters seek to develop and illustrate many of the

concerns that have already been voiced in the book: the first of

these focuses on some of the film festivals I’ve attended in recent

years; the second discusses the much misunderstood career of Orson

Welles, who, as an exemplary figure, continues to pose ideological

challenges to the film industry; and I conclude with a summary of my

arguments in the form of a self-dialogue that explains why I think the

audience is closer to being right than most industry “experts” admit.

Above all, I’m interested in isolating those elements in contemporary

American film culture that alienate us from its possibilities. If my

purpose in zeroing in on these misunderstandings is polemical, hence

“negative,” this is simply because they block us all from enjoying the

kind of positive experiences at the movies that are still theoretically

available to us—if only we know where to look.

End Notes

[1] This was in a 1996 essay (“The Last Taboo: The Dumbing Down of American Movies,” reprinted in Lopate’s Totally Tenderly Tragically, New York: Anchor Books, 1998, pp. 259–279). For more recent examples, consider There’s Something About Mary, Happiness, and Life Is Beautiful.

[2] I’m indebted to film scholar Susan Ohmer for alerting me to this article and sending me a copy.

Ernest Borneman was a German psychotherapist (1915–1995) who was also a novelist, playwright, cameraman, film director, screenwriter, writer for TV and radio, prolific journalist, and jazz musician. Borneman worked for Orson Welles in the late forties and early fifties by scripting an adaptation of Homer’s The Odyssey— eventually realized in altered and uncredited form by producers Carlo Ponti and Dino De Laurentis, actor Kirk Douglas, and director Mario Camerini as Ulysses (1955) — and by writing several scripts for the radio series The Adventures of Harry Lime; he was also apparently responsible for Welles’s discovery of Eartha Kitt. Borneman’s fascinating and multifaceted career—which began in the United Kingdom with studies in social anthropology and archeology and ended in Austria with studies in sexuality and child psychology—clearly merits further research; for most of the information in this footnote, I am grateful to Welles scholars Hans Schmid, who interviewed Borneman shortly before his death, and James Naremore, who lent me his copy of Borneman’s first novel, The Face on the Cutting-Room Floor (1937), a mystery credited pseudonymously to Cameron McCabe that includes a detailed account of Borneman’s career in its afterword (New York: Penguin Books, 1986).

[3] Albert Brooks — one of the movie’s costars, and a good friend of James Brooks — agrees with me. He said to Gavin Smith in Film Comment (July-August 1999), “I wish you could have seen the musical [version]. That was the greatest thing in the world, and it broke my heart that the movie came out like it did. The irony of that movie is, the very thing it was about was what it succumbed to. I mean, here’s a movie whose whole being is about testing and succumbing to the testing, and that’s exactly what happened to Jim [Brooks]. I understand why, but the ambition was so great, if he had stuck to it, in my opinion, it certainly wouldn’t have done any worse, and in the long run it would have been a really important movie.”

[4] “Rose-Tinted Spectacles,” in Seeing Through Movies, edited by Mark Crispin Miller, New York: Pantheon Books, 1990, p. 156.

[5] New York: Crown, 1998, Preface, p. vii.