From the Chicago Reader (April 22, 1994). — J.R.

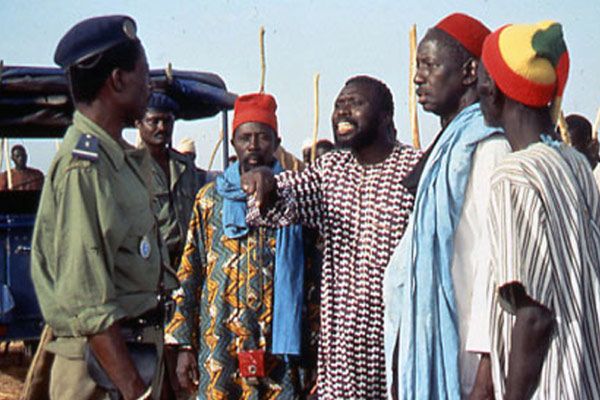

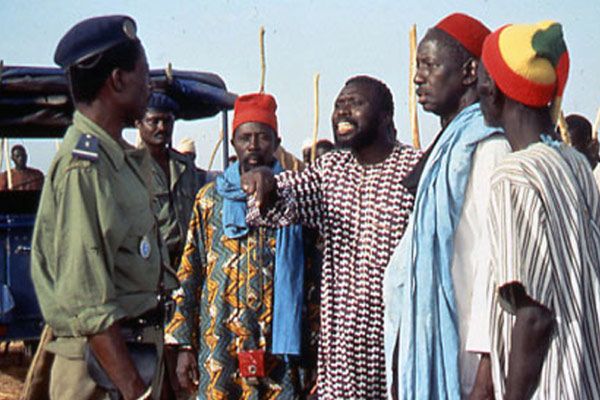

*** GUELWAAR

(A must-see)

Directed and written by Ousmane Sembène

With Omar Seck, Mame Ndoumbe Diop, Thierno Ndiaye, Ndiawar Diop, Moustapha Diop, Marie-Augustine Diatta, Samba Wane, and Joseph Sane.

We like to think that the essential works of any art form are readily available to everyone; but when it comes to film we still aren’t within hailing distance of that goal, even if we agree to the debatable proposition that a film’s transfer to video equals its availability. The canons of film history taught in film departments across the country are based almost entirely on the titles that film, video, and laser disc companies choose to place or keep on the market, which is all that most film professors have seen in the first place. And now that 16-millimeter film distribution is already on its last legs, the history and breadth of the medium, even for most film students, is quickly being reduced to what can be found at local video stores.

Among the many key items that can’t be found there are virtually all the major African films, including the seven features and four shorts of Senegalese writer-director Ousmane Sembène, by most accounts the greatest African filmmaker. Read more

My interview with Alain Resnais in New York in December 1980 yielded three separate articles, written for Soho News, American Film, and Omni. This is an unedited draft of the latter; I can’t recall now whether or not it was ever published in some form, but I think it probably wasn’t. The other two, which were published, are posted elsewhere on this site, here and here. -– J.R.

From the 42nd floor of Manhattan’s elegant Park Lane Hotel, where French director Alain Resnais has been holding court, Central Park in the winter looks remote and unfamiliar, like the terrain of another planet. It resembles Resnais’ unexpected smash hit Mon Oncle d’Amérique -– a unique, original blend of art and science –- by resisting precise description almost as confidently as it invites contemplation and wonder. And if the angle of vision that helps to account for this strangeness faintly suggests the vantage point of an amused yet saturnine deity, gazing down almost nostalgically, something of the same ambiance seems to inform the relation of the 58-year-old Resnais to his haunting comedy.

A master director who’s also a master of indirection -– always electing to tell a story in a different offbeat manner -– Resnais has never scripted any of his own features, But all of them are unmistakably personal reflections, generally about the past. Read more

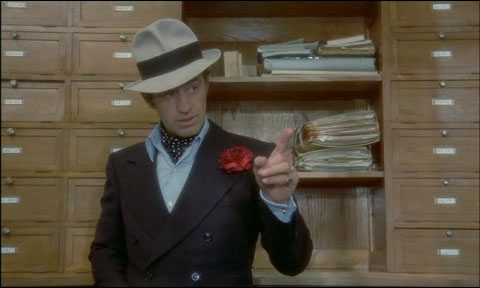

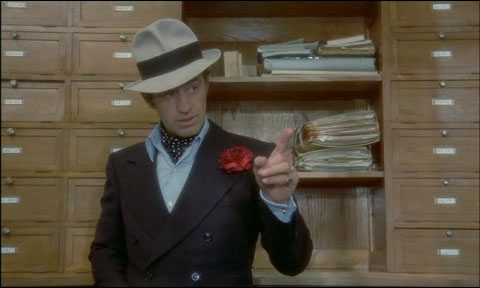

From Film Comment (March-April 1974). — J.R.

December 7: To enter the sound stage at Epinay-sur-Seine, a Parisian suburb where Alain Resnais is working on his new film about Alexandre Stavisky, you have to go through a heavy door that resembles the entrance to a bank vault, where you’re promptly greeted by Alexandre, a friendly dog who seems to be serving as the crew’s mascot (a younger dog named Sacha figures in the cast). Continuing past Alexandre, you weave your way through a labyrinth of construction that eventually resolves itself into a gargantuan neo-Lubitsch set comprising Stavisky’s office complex — a rather awesome 1933 décor the size of a country house that took forty people a month to build, even though it’ll only be used for a relatively short part of the film.

It’s the kind of set you can get lost in, with multiple exits and three separate stairways leading off of a giant central conference room with golden chandeliers, a large semi-circular table, light-green walls, tall windows with pink drapes, and no ceiling; a set where long hallways on the second landing go past doors that open on nothing, and members of the lighting crew move about in obscure corners carrying equipment and muttering to themselves. Read more

From Film Comment, November 1974. I suspect that one factor that may have kept me from scanning and posting this column until now, at least in its complete form, is my dissenting view of CHINATOWN and WHAT?, even before the former became fully canonized as Holy Writ. -– J.R.

Moving across the Channel, a profound difference in the cinematic climate becomes immediately apparent. How could it be otherwise, considering that the lifestyles that go with each city are so strikingly antithetical? Paris is all adrenalin and shiny surfaces, hard-edged and brittle and eternally abstract, the capital of paranoia (cf. Rivette) and street spectacle (cf. Tati), where café tables become orchestra seats as soon as the weather gets warm — the city where everyone loves to stare. London is just the reverse, a soft-centered cushion of comfort where trust and accommodation make for a slower, saner, and ostensibly less shrill mode of existence: relatively concrete and prosaic, more spit and less polish, a city more conducive to eccentricity than lunacy. Relatively speaking, London isn’t a movie town. It’s considerably easier to go out to films in Paris and to be more selective about what one sees, because the area is smaller and the action tends to be more concentrated. Read more

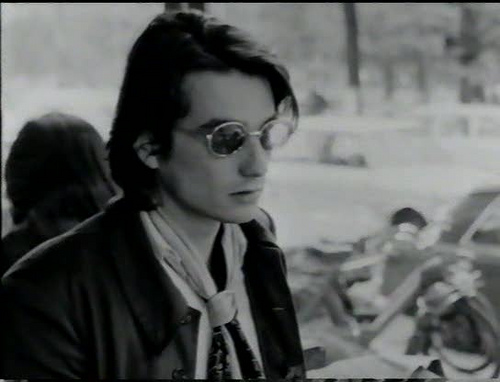

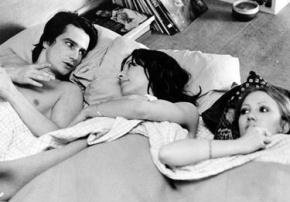

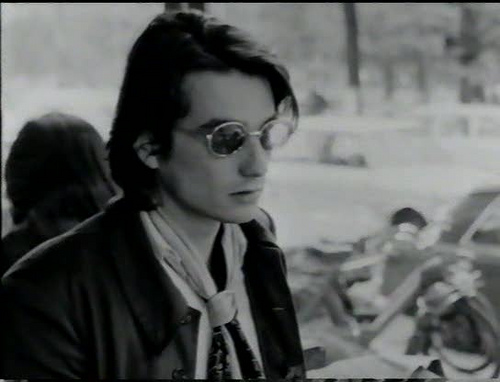

From Sight and Sound (Winter 1974-75). — J.R.

“The day I stop suffering, I’ll have become someone else.” “There’s no such thing as chance.” “To speak with the words of others — that’s what I’d like. That’s what freedom must be.” From the Café aux Deux Magots to the adjacent Flore, from the streets and sidewalks of a grayish Paris to other people’s flats, for the better part of 219 minutes, Alexandre (Jean-Pierre Léaud) continues to hold forth. “In May ’68 a whole café was crying. It was beautiful. A tear-gas bomb had exploded . . . a crack in reality opened up.” Charmingly, narcissistically, elaborately, endlessly: “I don’t do anything; I let time do it.” “Abortionists are the new Robin Hoods . . .the scalpel replaces the sword.” “The world will be saved by children, soldiers” (pregnant pause) “and fools.”

Much less talkative is his beloved Gilberte (Isabelle Weingarten—a Bresson discovery back for another nonperformance), who forsakes him to get married, and Marie (Bernadette Lafont), the older woman he lives with, casually exploits, and is clothed and fed by. But a verbal match of sorts is offered by the doleful and doelike Veronika (Françoise Lebrun, in an extraordinary, glowing debut), a promiscuous nurse he picks up one afternoon. Read more

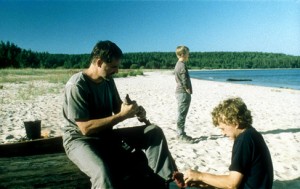

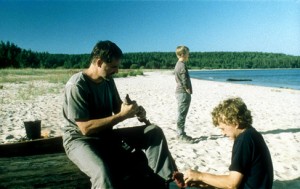

From the Chicago Reader (April 30, 2004). It’s great to catch up with Andrey Zvyagintsev again a decade later, thanks to his wrenching and politically caustic Leviathan. — J.R.

Beautifully structured and emotionally wrenching, this 2003 debut feature immediately establishes Russian filmmaker Andrey Zvyagintsev as a master. It charts a father’s uneasy return to his wife and two adolescent sons after a long and unexplained absence, a reunion capped by his ill-fated fishing trip with the two boys. A former actor, Zvyagintsev elicits first-rate performances from his male leads, but what registers most is the sharpness and intensity of his vision of nature and childhood experience. Nominated for an Oscar and winner of the Golden Lion at the Venice film festival, this has been described by the director as “a mythological look [at] human life,” as accurate a description as any I’ve encountered. In Russian with subtitles. 106 min. Music Box.

Read more

Read more