From the Chicago Reader (July 1, 2001). — J.R.

I’m still trying to decide if this 146-minute piece of hocus-pocus (2001) is David Lynch’s best feature between Eraserhead and Inland Empire. In any case, it’s immensely more likable than his other stabs at neonoir (Blue Velvet, Wild at Heart, Lost Highway), perhaps because it likes its characters and avoids sentimentalizing or sneering at them (the sort of thing that limited Twin Peaks, at least in spots). Originally conceived and rejected as a TV pilot, then expanded after some French producers stepped in, it has the benefit of Lynch’s own observations about Hollywood, which were fresher at this point than his puritanical notations on small towns in the American heartland. The best-known actors (Ann Miller, Robert Forster, Dan Hedaya) wound up relatively marginalized, while the lesser-known talents (in particular the remarkable Naomi Watts and the glamorous Laura Elena Harring) were invited to take over the movie (and have a field day doing so). The plot slides along agreeably as a tantalizing mystery before becoming almost completely inexplicable, though no less thrilling, in the closing stretches — but that’s what Lynch is famous for. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (October 13, 1998). — J.R.

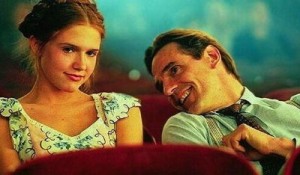

Though Adrian Lyne’s clodhopper direction, underlined by a mushy Ennio Morricone score, predictably runs the gamut from soft-core porn in the manner of David Hamilton to hectoring close-ups, this is perhaps Lyne’s best movie after Jacob’s Ladder — a genuinely disturbing (if far from literary) adaptation of Nabokov’s extraordinary novel, written by former journalist Stephen Schiff and starring, predictably, Jeremy Irons. It shines in the areas where Stanley Kubrick’s 1962 adaptation is deficient: Dominique Swain, the actress playing Lolita here, actually looks 14, making this much more a story about corrupted innocence, and it unfolds in American locations in the late 40s. In every other respect, however, Kubrick’s version is superior and will clearly endure as the better movie: Frank Langella as Quilty can’t hold a candle to Peter Sellers, and Melanie Griffith plays a poor second to Shelley Winters as the heroine’s mother. Your time would be better spent reading or rereading the novel than seeing either film version, but this overproduced 1998 art film has its moments. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (April 1, 1990). Thanks to the interview with Casper Tybjerg on Criterion’s dual-format release, I’m no longer sure if this was Dreyer’s “first substantial commercial release outside Scandinavia,” because Michael, made just before in Germany, also reportedly made a considerable splash. — J.R.

Formally and politically decades ahead of its time, Carl Dreyer’s wonderful silent Danish comedy (1925), his first substantial commercial success outside Scandinavia, recounts what happens when a working-class wife and mother, prompted by an elderly nurse, walks out on her tyrannical and demanding husband, who then has to fend for himself. Restricted mainly to interiors, Dreyer’s masterful mise en scene works wonders with the domestic space, and his script and dialogue make the most of his feminist theme. 110 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the June 22, 2000 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

The Ontario Film Review Board has banned this history of U.S. marijuana laws because it contains 20 seconds of archival footage showing rhesus monkeys and chimpanzees smoking dope in a lab experiment. Apparently this violates the Ontario Theatres Act, which forbids abuse of an animal in making a film, although the board showed no concern about mice falling off a table or fish swimming sideways in the same sequence (at least the simians seem to be enjoying themselves). A better example of animal abuse might be compelling a filmmaker to submit his work to censors or incarcerating untold thousands of kids for having harmless fun while hypocritical state agents and presidents show an almost total lack of interest in the truth or falsity of their own antidrug propaganda. Director Ron Mann specializes in documentaries celebrating countercultural forms and practices (Comic Book Confidential, Twist, Poetry in Motion, Imagine the Sound); this hilarious yet frightening piece of agitprop, using found footage, period music, jaunty animated titles, and narration by Woody Harrelson (written by Solomon Vesta), is as entertaining and informative as anything Mann’s ever done and as good an example of grass humor as you’re likely to find. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (September 1, 1992). — J.R.

It seems almost impossible that someone could vulgarize and coarsen Tom Wolfe’s best-selling novel any further, but leave it to director Brian De Palma, working here with a script by Michael Cristofer, to plumb uncharted depths. Wolfe’s conservative, page-turning satire pretending to be centrist is the tale of Sherman McCoy, a young multimillionaire bond trader (Tom Hanks) who takes a wrong turn and winds up in the south Bronx, where his car hits a young black man, whose companion may have been trying to mug McCoy. The compromising circumstance of McCoy’s mistress being in the car with him doesn’t help matters when he finds himself at the center of political machinations involving among others a black religious leader (John Hancock), a district attorney running for mayor, and a down-and-out alcoholic reporter. It’s easy enough to accept the unconvincing Brit journalist of the original being turned into an American narrator played by Bruce Willis. But the novel — informed by some sophistication about New York politics and life-styles even as it refrained from entering the consciousness of a single female or nonwhite character — is predicated on our never knowing (or caring too much) what actually happened in the south Bronx; the movie removes such ambiguity, couldn’t care less about accuracy (a white teacher at a ghetto high school is seen waxing his expensive sports car), turns the mistress (already a conniving bitch) into a bimbo, gets most of its kicks from moronic dialogue (including a truly offensive gag about AIDS), and then wraps things up with a self-righteous sermon by a black judge (Morgan Freeman) — a white judge in the novel — that concludes, Go home and be decent people. Read more

From the September 1, 1991 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

It’s a fair sign of the capriciousness of the American press that it took this crass 1991 movie to get the media to discuss the assassination of John F. Kennedy; sad to say, Oliver Stone’s three hours of bombast did little to raise the level of discussion. As someone who doesn’t believe much of the Warren Report, I’m favorably disposed toward any movie that seriously questions it, but Stone’s all-purpose conspiracy theory, built like a house of cards, rivals Mississippi Burning in its sheer crudeness and contempt for the audience. Like New Orleans district attorney Jim Garrison —who investigated the assassination in the late 60s and is played as a spotless white knight by Kevin Costner — Stone and cowriter Zachary Sklar, hampered by harassment and multiple cover-ups, find themselves stuck for a suspect and focus their anger on gay businessman Clay Shaw (Tommy Lee Jones), hoping that homophobic melodrama (complete with a wholly invented male hustler played by Kevin Bacon and a dubious inflation of Shaw’s CIA connections) will paper over the gaps left in the argument. What emerges has its compelling moments, but the obfuscation needed to put it across matches the Warren Report’s desire to oversimplify. Read more

From the October 1, 1997 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

This 1997 British film updates Henry James’s late novel in more ways than one, not only setting the story several years later but also inverting the morality of the original: in keeping with 90s ethics, the gold-digging villains have been transformed into sympathetic heroes. By literary standards this is disgraceful, but for armchair tourists and oglers it’s a nice, glossy spread. Apparently director Iain Softley and screenwriter Hossein Amini decided, contra prudish James, that marrying a dying American heiress for her loot is exactly what a penniless English journalist should do, even when it involves the collusion of his mistress, so heiress Milly Theale, the soul of the novel, barely exists here. This movie is about pretending to catch up with what you didn’t read in college, and oohing and aahing over conspicuous consumption and pretty sites in Venice, including Helena Bonham Carter’s bare ass. With Linus Roache, Alison Elliott, Elizabeth McGovern, Charlotte Rampling, and Michael Gambon. R, 101 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (September 27, 1991). — J.R.

John Cassavetes’s first crime thriller (Gloria was the second), a post-noir masterpiece, failed miserably at the box office when it was first released in 1976; two years later, he released this recut, shorter, and equally good version, which didn’t fare much better. Actually more a personal and deeply felt character study than a routine action picture, it follows the last days of Cosmo Vitelli (Ben Gazzara at his very best), the charismatic owner of an LA strip joint who recklessly gambles his way into such debt with the mob that he has to bump off a Chinese bookie to settle his accounts. In many respects the film serves as a summation of Cassavetes’s view of what life is all about. In fact what makes the tragicomic character of Cosmo so moving is that Cassavetes regarded him as his alter ego — the proud impresario and father figure of a tattered show-biz collective (read Cassavetes’s actors and filmmaking crew) who must compromise his ethics to keep his little family afloat (read Cassavetes’s career as a Hollywood actor). Peter Bogdanovich used Gazzara in a similar part in Saint Jack (1979), but as good as that film is, it doesn’t catch the exquisite warmth and delicacy of feeling of Cassavetes’s doom-ridden comedy-drama. Read more

From the January 29, 1999 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

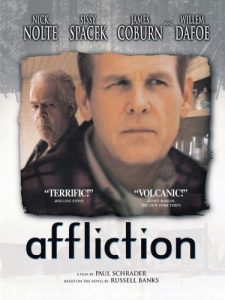

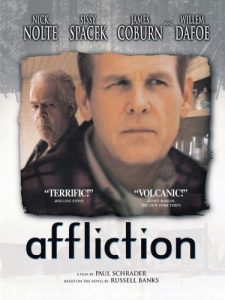

Because most of the acting is authentic and powerful (especially that of Nick Nolte, Sissy Spacek, and Jim True), the source (a Russell Banks novel) is more than respectable, and the subject — an all-around fuckup (Nolte) in a dying New England town becomes even more fucked-up — and winter setting are unrelentingly grim, one has to admire writer-director Paul Schrader for having the guts to make this picture. But I found it more punishing than edifying. A brave effort to stare down the specter of American failure, it gets off on the wrong foot by pretentiously turning the doomed hero into a Christ figure — a traffic cop with arms extended in crucifixion mode — before the story even gets started. Flashbacks come in two subjective styles — grainy and handheld to recount the meanness and violence of the hero’s awful father (James Coburn, a bit out of his depth), black-and-white to reconfigure the recent past. The hero’s brother (Willem Dafoe), daughter (Brigid Tierney), and ex-wife (Mary Beth Hurt) all have their say, but the narcissism of wounded macho gets in the last word, and it’s last year’s groceries. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From The May 22, 2000 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

This is obviously a sequel, but whether its true predecessor is Mission: Impossible, Face/Off, or Dr. No is less certain. Like its predecessor, it stars coproducer Tom Cruise, costars Ving Rhames, was written at least partially by prestigious hack Robert Towne (who takes solo credit here), and whimsically glorifies the CIA as a band of efficient sophisticates devoted to inventing new ways for its employees to perform fancy stunts. Like Face/Off, it was directed by John Woo, features a fair amount of sadistic cruelty, and dispenses so many rubber masks to allow the characters to swap identities that no hero or villain winds up carrying any moral weight at all. (How they sometimes manage to imitate one another’s voices is poorly explained, but credibility is so thin throughout that this movie only came into its own when it became available on video and thus truly disposable.) Like Dr. No, it’s a piece of nostalgia for colonialism (the main urban setting is Sydney), Playboy, Cary Grant, high-tech gadgets, and apocalyptic fantasies, and if Cruise makes an unconvincing Bond when compared to Sean Connery, Anthony Hopkins is perfectly cast as Cruise’s chief, and Thandie Newton — as a thief enlisted by the CIA to fuck her former boyfriend, villain Dougray Scott — arguably makes an even better babe than Ursula Andress. Read more

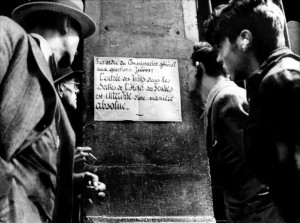

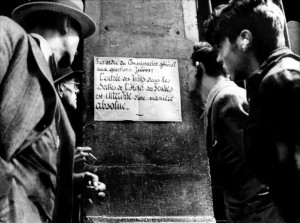

The cinema has produced few more impressive pieces of investigative journalism than this epic 1971 documentary by Marcel Ophuls — 260 minutes long, plus a 15-minute intermission — about the German occupation of France. Ophuls, son of the great Max Ophuls, devotes the first part to the fall of France, the second part to everyday life during the Occupation up through the Liberation. In both parts he focuses on the city of Clermont-Ferrand, not far from Vichy, and the heart of the film consists of relaxed interviews with survivors — French as well as German, resistance fighters as well as collaborationists — and newsreels and propaganda films from the period. The interviews are dated somewhat by the dearth of female subjects (only one out of the 36 principal speakers, and a Petain supporter at that); women are often visible, but apart from the occasional interjection they function mainly as domestic decor. One of the film’s abiding strengths is Ophuls’s refusal to rely on easy ironies or facile divisions between heroes and villains, despite his implicit emphasis throughout on ethical issues. Near the beginning and end of the film he employs the unsettling technique of freezing the frame while the subject’s voice continues, which suggests that even the “frozen” past still has fresh things to tell us. Read more

A very special movie, about two jazz musicians with Tourette’s syndrome getting acquainted in Greenwich Village. One’s a white 12-year-old pianist (Christopher George Marquette); the other’s a black tenor saxophone player (Gregory Hines). Polly Draper (Thirtysomething), who does a beautiful job of playing the boy’s mother, wrote the sensitive script, which falters only when it reaches for an overly hasty resolution. She’s the wife of jazz pianist Michael Wolff, who’s in charge of the music here and has a mild case of Tourette’s, so she has a particular reason to be thinking about some of the fascinating questions posed hereabout willful and involuntary improvisation and how they might live together. The moments when the story and music become one are sublime, and more generally this is a very sweet and touching story about various West Village people. The jazz milieu is caught with flavor and feeling. With Desmond Robertson, Bill Nunn, and Tony Shalhoub. 91 min. (JR) Read more

From the Chicago Reader (September 24, 1996). — J.R.

The standard line on this actor-heavy, brain-light concoction by writer-director John Herzfeld (1996) is that it’s Short Cuts meets Pulp Fiction, but it isn’t a tenth as good as either. It does, however, have a good many dog reaction shots, so if you happen to think the other two movies were lacking in those, credit Herzfeld for making up the difference. Crosscutting between various San Fernando Valley miniplots that prove to be interlocking, Herzfeld has a tolerable eye for filling a ‘Scope frame but a tin ear when it comes to creating dialogue; these are all characters we’ve met before, and most even seem bored with themselves. With Danny Aiello, Greg Cruttwell, Jeff Daniels, Teri Hatcher, Glenne Headly, Peter Horton, Marsha Mason, Paul Mazursky, James Spader, Eric Stoltz, and Charlize Theron, plus cameos by Keith Carradine, Louise Fletcher, and Austin Pendleton. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (October 1, 1992). — J.R.

A vast improvement on Edward Dmytryk’s 1954 The Caine Mutiny, directed by Robert Altman for TV in 1988. Both are adaptations by Stanley Roberts of Herman Wouk’s ultraconservative novel, but the Dmytryk essentially honors the promilitary message of the original (navy captains should be obeyed even if they’re insane) while the Altman version ridicules it. One of Altman’s best works of the 80s; with Eric Bogosian, Jeff Daniels, Brad Davis, Peter Gallagher, Michael Murphy, and Kevin J. O’Connor. (JR)

Read more

“I must admit,” the Bear said in an icy voice, “that I have indeed always considered death a tragedy.”

“And you were wrong,” said Paul. “A railway accident is horrible for somebody who was on the train or who had a son there. But in news reports death means exactly the same thing as in the novels of Agatha Christie, who incidentally was the greatest magician of all time, because she knew how to turn murder into amusement, and not just one murder but dozens of murders, hundreds of murders, an assembly line of murders performed for our pleasure in the extermination camp of her novels. Auschwitz is forgotten, but from the crematorium of Agatha’s novels the smoke is forever rising into the sky, and only a very naive person could maintain that it is the smoke of tragedy.”

–Milan Kundera, Immortality (1990) [10/4/09] Read more