This review, originally published in August 3, 1990 Chicago Reader, was one of my first sustained efforts to write about the employment of jazz in movies. The movie isn’t as good or as entertaining as Lee’s latest messy Brechtian musical, Chiraq, although the latter film suggests once again that he still doesn’t have a clear sense of how to use music. — J.R.

MO’ BETTER BLUES ** (Worth seeing)

Directed and written by Spike Lee

With Denzel Washington, Lee, Wesley Snipes, Giancarlo Esposito, Robin Harris, Joie Lee, Cynda Williams, Bill Nunn, Dick Anthony Williams, and John Turturro.

by Jonathan Rosenbaum

First the good news: strictly as an exercise de style, Spike Lee’s fourth joint is in certain respects the liveliest and jazziest piece of filmmaking he’s turned out yet. From the arty close-ups behind the opening credits of — and liquid pans past, and dissolves between –- trumpet, lips, and lovers’ grasping hands in blue, yellow, amber, and green to the matching semicircular crane shots that frame the story, this is a movie cooking with ideas about filmmaking. Bringing back a good many of the featured players in Do the Right Thing, and introducing to the Spike Lee stable the highly talented Denzel Washington, Cynda Williams, Wesley Snipes, and Dick Anthony Williams (among others), it’s a movie bursting with personality and actorly energy as well.

Unfortunately, when it comes to characters, story, music, and the relationships between the three, Mo’ Better Blues is both confused and unconvincing — a lot of loose ideas and platitudes rattling around in search of a movie. If I hadn’t expected more from Lee than simple diversion, the fair-to-middling music and the razzmatazz visuals might have sufficed. It all depends on what you’re looking for; personally, I was hoping for a jazz movie and a love story.

On the basis of his previous movies — particularly the last two, School Daze and Do the Right Thing -– it was easy to predict that Lee would have trouble with a movie about a jazz musician. Both of those movies have unnecessarily cluttered scores that seem to imply, as a matter of general principle, that any music at all is better than none –- which means that at times the music competes with dialogue, distracts from the actors and mise en scène, and assigns anomalous moods and meanings to scenes that would work perfectly well without them. Insofar as such tactics tend to camouflage dead moments in the script or direction –- at the same time they banish silence and its virtues from the sound track — one could make the ungenerous assumption that Lee is using them cynically, to hide his own weak spots, but I don’t think this is his main motivation. Since I believe that Lee is serious, personal, and complex as a filmmaker in a way that, say, Brian De Palma is not, I think the problem runs much deeper, and is closer to the kind of artistic conflict that one finds in the work of someone like Martin Scorsese.

Without delving too deeply, questions about Lee’s family dynamics seem unavoidable considering the peculiar stresses in his work. The scores for all of his features, written by his father, jazz bassist and composer Bill Lee, are invariably cluttered orchestral works that function less as film scores than as rather pretentious autonomous compositions. (One can find a related if usually less severe problem in Francis Coppola’s occasional use of music by his father, Carmine.) The fact that Lee comes, as he puts it, from a “jazz household” was part of his stated motivation for making the film, and while it may give Mo’ Better Blues a bit more backstage authenticity than either Round Midnight or Bird, Lee’s movie has a considerably less developed feeling for the music.

Whatever the specific motivations, the music seems to provoke –- or at least become the occasion for –- a lack of certainty in Lee’s directing and editing that usually takes the form of scattershot restlessness. (I’m not speaking so much of his admirable eclecticism, which he shares with Scorsese, as of the impression that he’s floundering when he has to work directly in relation to music.) Skittishly leaping from one shot to the next or between a stationary and a moving camera, and (to an even greater extent) relying too heavily and frequently on close-ups, Lee gratuitously hypes up his shots — much the way a beginning writer might overuse italics or exclamation points. It’s as if he felt obliged to simultaneously adhere to his father’s hectoring structures and break free of them, without a battle plan for how to proceed on either front.

The anxious moves that ensue point to Lee’s succumbing to the music-video syndrome: they generally have nothing to do with building a structure and everything to do with reaching for immediate effects that often make larger structures impossible, which actively works against many of Lee’s larger dramatic aims. The results are an overloaded sound track and overloaded direction that often barely seem to be on speaking terms, although they’re both churning away at full blast. And as mistrustful as I generally am of vulgar Freudianism, it’s hard to overlook the oedipal conflicts that crop up in the plots of School Daze and Do the Right Thing, made especially complex in the latter case because the father figure, Danny Aiello, is white. In Mo’ Better Blues, father and son are complicitous buddies, but the implied inevitability of the son replicating the attitudes of the father produces a number of ambiguities and ironies, not all of them hopeful.

The basic plot of Mo’ Better Blues is so hackneyed that it could be described this way: Gifted Jazz Trumpeter Bleek Gilliam (Washington) Is Too Obsessed With His Art to Care for Feelings of Others or to Realize That His Best Friend Giant (Lee), a Compulsive Gambler, Does a Lousy Job of Managing His Quintet and Keeping White Club Owners (John and Nicholas Turturro, a Tweedledum and Tweedledee Act) From Exploiting Them. Selfish Bleek Romances Two Women at Once, Indigo (Joie Lee) and Clarke (Cynda Williams), and Is Indifferent to the Musical Ambitions of Both Clarke and His Sax Player Shadow (Wesley Snipes). When Both Ladies and the Gangsters Who Back Giant’s Bookie Converge at the Club, Giant Is Seriously Beaten; Bleek, Coming to His Defense, Gets His Chops Busted, Ending His Career as a Musician, Then Falls From Sight . . .

I’m not claiming that such a plot is unserviceable, only that Lee conceives of it in more or less these simplistic terms, without much shading or nuance. (And with a few changes, Bleek, his loft, and his two girlfriends become in many ways a replay of the heroine, her loft, and her boyfriends in She’s Gotta Have It, Lee’s first feature.) He clearly wants to use this plot much the same way that a jazz musician uses a popular standard, as a basis for riffs and improvisations –- beginning and ending his movie with virtually identical sequences the way a jazz musician begins and ends a number with a given theme. It’s a legitimate enough approach, and, up to a point, Lee manages to justify it with his ideas and his energy. But it’s a concept that ultimately gets him into trouble.

A good jazz musician will use a familiar theme not merely as a point of departure but as a site for rediscovery. But Lee’s use of familiar themes remains perfunctory. Bleek’s obsession with his music is a given, but nothing that we see or hear fleshes out this concept in a persuasive or compelling way, and Washington himself is much too poised and self-contained to suggest Bleek’s obsessiveness. (His trumpet playing, dubbed by Terence Blanchard, is basically Miles Davis twice removed –- and subdued –- by way of Wynton Marsalis, Freddie Hubbard, and other postmodernist Miles imitators: obsessive is the last thing that anyone would call it. And an extended rap piece that Bleek writes and performs with his group, called “Pop Top 40,” is arguably not even very musical, whatever its other virtues.)

When Bleek disappears for a year, we have no idea where he goes or what he does, or even whether his family knows of his whereabouts, and significantly we don’t much care. We accept the vagueness — if we accept it –- like so much else in the film, as a mere trope filling out a design, similar to the long stretches of background music that we aren’t supposed to hear so much as overhear (a curious attitude to take toward the music that the movie’s romantic hero is supposed to be obsessed with). And when we hear Clarke sing for the first time, toward the end of the film soon after Bleek’s return from the netherworld, it isn’t clear whether he’s hearing her sing for the first time as well –- which would be important if the characters had any depth. Similarly, Bleek’s friendship with Giant and his relationships with both Indigo and Clarke are never distinctive enough to convey any sense of urgency or uniqueness. Regrettably, the only motifs in the story that seem to energize Lee’s writing are Bleek’s relationship to his father and the familiar theme of competition -– whether it’s between Bleek and Shadow or between Indigo and Clarke -– and even here, the plot points occasionally seem forced. (Though both Giant and Bleek complain about Shadow’s solos being too long, for instance, we never hear anything to substantiate this charge.)

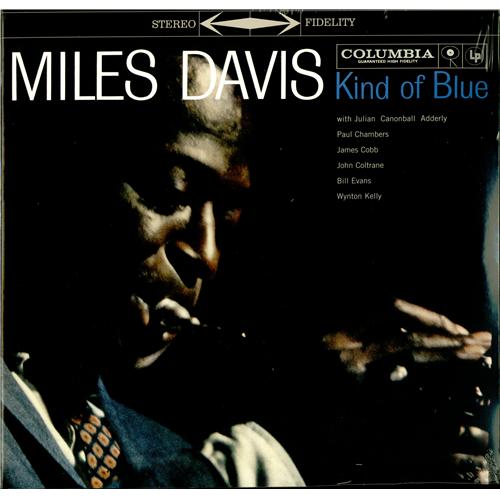

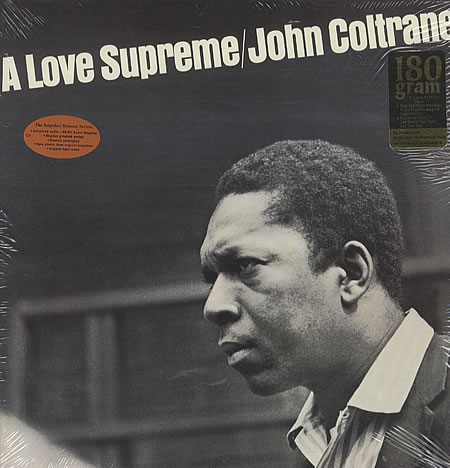

I’m not claiming that Lee doesn’t have any ideas about how to use and integrate music in his film; the problem, rather, is that he doesn’t know how to sustain them. Two of his best ideas are “improvisations” of mise en scène based on particular well-known jazz pieces — Miles Davis’s first recording of “All Blues” (from the classic Kind of Blue album) and “Acknowledgement,” the opening movement of John Coltrane’s A Love Supreme. “All Blues” is a moody Davis composition written in 6/8 time, with a pronounced sense of three beats (a mournful unison background riff) against four (a wailing trumpet solo). Lee uses it to accompany a lovemaking scene between Bleek and Clarke, and he lyrically translates this notion of three against four, and riff against melodic line, by making Bleek’s loft appear to spin in a dreamy circle around the couple (corresponding to the riff) while they (corresponding to the trumpet solo) remain fixed in the foreground. It’s a lovely idea, but Lee doesn’t seem to know how to follow it up; other shots that are stylistically unconnected follow as the song continues, with the consequence that the music becomes less and less important, eventually serving as mere background bustle. This means that what starts out as a tribute to the music winds up as a minor insult to it.

In the case of A Love Supreme –- which Lee planned to name his film after, until Coltrane’s widow denied him permission, reportedly because of the film’s use of profanity –- Lee again starts off with a powerful idea that he quickly dissipates. “Acknowledgement” begins magisterially with an almost out-of-tempo tenor sax cadenza accompanied by impressionistic cymbal work (by Elvin Jones) that suggests the pulse of crashing waves –- something closer to a pure, burnished sound than a steady succession of beats or notes. Lee uses the piece just after Bleek’s climactic reunion with Indigo, accompanied by a gorgeous long shot of the Statue of Liberty and the Staten Island ferry under a blood red sky. It’s a lovely epiphany that, like the earlier one, becomes more and more diluted by further shots detailing their reunion and other subsequent events, all of which eventually grinds the music underfoot –- and literally buries it under other sounds -– instead of illustrating or enhancing it, as it was apparently meant to do.

To my mind, the only time that Lee succeeds in integrating jazz dramatically for anything longer than a single shot is toward the end of the film when Clarke sings “Harlem Blues” with Shadow and Bleek’s former rhythm section. The cutting here is almost as nervous as it is during the other musical numbers, but because this is the first and the only time that we hear her sing -– and a moment that coincides with the return of Bleek to the jazz world — the scene carries a punch that not even Lee’s directorial uncertainties can undermine. (By contrast, the nadir of his editing to music is his ludicrously cornball crosscutting between Giant getting beaten on the street and aggressive shots of the musicians playing inside the club — a concept, linking jazz to violence and back alleys, that was cheap and old hat even back when Richard Brooks used it to juice up an alley bashing in Blackboard Jungle in 1955.)

An entertaining failure packed with incidental pleasures, Mo’ Better Blues is no less personal and independent a work than Lee’s other features, and in some ways it’s even more experimental. It gives us our last opportunity to savor the comic gifts of the late Robin Harris (one of the sidewalk kibitzers in Do the Right Thing, who here plays a nightclub comic very much like himself), a highly stylized view of New York that is quite different from the New Yorks of She’s Gotta Have It and Do the Right Thing, some hip nods to jazz history (in the names of clubs and in the musical montage heard over the final credits), and lots of lively wit in the dialogue.

Furthermore, one can only applaud the overall spirit of experimentation, especially in the editing, that leads to highly unconventional sequences reflecting the characters’ particular states of mind: Bleek’s literal confusion between Indigo and Clarke is effectively illustrated by a series of graceful matching cuts (evocative of Buñuel’s That Obscure Object of Desire) that have him making love to and arguing with both of them at the same time; later, Lee charts the mutual uncertainties of Bleek and Indigo, when they meet after a year apart, with highly disconcerting mismatches in the editing. For all the confusion and inadequacy on view here, Lee can’t be accused of either backing away from the promise of Do the Right Thing or following the abject practice of attempting a sequel or remake. For better and for worse, you might just say that like his dimly imagined hero, he’s simply trying a few things out.