From Film Comment (July-August 1999). I’ve done a light edit, trimming part of my original conclusion. It’s worth adding that at least two additional pieces about this film have recently turned up on the Internet — a new essay by Ignatiy Vishnevetsky (the first part of an ongoing series) and a detailed account by the late Gilbert Adair that was originally published in 1987, not long after Affaires Publiques was rediscovered in Paris.

I apologize for the poor quality of most of the illustrations from Bresson’s short film, which are the best that I could find. — J.R.

Ten years ago, I flew all the way from Chicago to the San Francisco Film Festival for a weekend to see Robert Bresson’s first film, which had been discovered in incomplete form at the Cinémathèque Française, bearing the title Béby Inauguré. Shorn of three of its musical numbers and now totaling 23 minutes, this rather elaborate piece of slapstick and surrealist tomfoolery was written and directed by Bresson and released in 1934, a full nine years before shooting started on his first feature, Les Anges du péché, and I had been hearing about it for years as an irretrievably lost curiosity. When asked in some interview what the film was like, Bresson had reportedly replied, “Like Buster Keaton, only much, much worse.” But then, after the incomplete film was found, one heard that he was pleased rather than appalled about the recovery.

Prior to the festival screening, Paul Schrader, who hadn’t yet seen the film either, offered a detailed introduction that outlined his transcendental interpretation of Bresson’s work. In a way this totally irrelevant and incongruous preparation for Affaires publiques proved to be almost as hilarious as the film itself, as if one of the royal dignataries ridiculed by Bresson in the film had offered his own thumbnail sketch of the proceedings. Though a sense of humor has never seemed one of Schrader’s strong points, his dogged efforts to enforce a metaphysical reading of one of the world’s most physical filmmakers were completely derailed by the film itself, which is a good deal closer in spirit to Million Dollar Legs, Duck Soup, and Jean Vigo’s Zéro de conduite — not to mention Alfred Jarry’s Ubu roi — than it is to either Diary of a Country Priest or Pickpocket.

As it happens, Schrader’s wasn’t the only blatant critical gaffe I encountered at the festival. That same weekend, I was lucky enough to see Souleymane Cissé’s sublime Yeleen for the first time, and was shocked to learn from Michael Sragow that this film as well as Tian Zhuangzhuang’s remarkable The Horse Thief demonstrated that the San Francisco Film Festival was more interested in ethnography than in art. To my mind, both misreadings ultimately stem from a reluctance to deal with films in terms of sound and image; Schrader’s spiritual grid and Sragow’s ethnocentric grid both derive from personal agendas that factor out much of what the filmmakers are doing. Nevertheless, I felt then and would still maintain today that Affaires publiques is more Bressonian than it’s generally cracked up to be, and the following remarks are an attempt to explain why.

Part of the problem we have in seeing (and hearing) Bresson clearly is that we tend to stereotype him in relation to a system. One of the more interesting revelations found in his interviews witgh Schrader (1977) and Michel Ciment (1983) — both reprinted in James Quandt’s invaluable Robert Bresson (Cinémathèque Ontario, 1998), which also reprints William Johnson’s thoughtful review of Affaires publiques for Film Quarterly — is his explicit denial that his style has anything to do with Jansenism, however much he may believe in predestination. Another discovery came in David Ehrenstein’s “Bresson and Cukor: Histoire d’un correspondence” (Positif no. 430, decembre 1996), which reported that Bresson wrote to George Cukor in 1964, when he was planning to make Lancelot du lac in English, to request his assistance in acquiring Burt Lancaster asnd Natalie Wood as his two leads. Both these revelations, by freeing us from the illusory necessity of keeping Bresson chained to the archetypal Bresson system — in these cases, Jansenism and a refusal of professional actors — match the bracing lucidity of Shigehiko Hasumi’s groundbreaking 1983 book on Yasujiro Ozu, a French translation and adaptation of which was published last year by Cahiers du cinéma. Explicitly countering the transcendental readings of Ozu by Schrader, Donald Richie, and others, Hasumi also seeks to liberate Ozu from the negative descriptions that have encrusted most of the criticism about his work and the characterizations of that work as “typically Japanese”. The final chapter of Hasumi’s book, “Sunny Skies,” is available in English in the collection of essays on Tokyo Story edited by David Desser for Cambridge University Press (1997), and one sentence in particular seems equally applicable to Bresson: “Ozu’s talent lies in choosing an image that can function poetically at a particular moment by being assimilated into the film, not by affixing to the film the image of an object that is considered poetic in a domain outside the film.”

In the kingdom of Crogandie, a frenetic radio broadcaster jabbers away while a demonstrative soprano sings silently on the other side ofa soundproof window; in the film’s final shot, the window is smashed while the chancellor’s chauffeur wrecks the studio and the soprano’s voice finally breaks through. (In fact, the stopping and starting of music is a recurring motif throughout.) In between these two shots is a lot of knockabout farce involving the chancellor (played by the clown Béby) at four public ceremonies, each one presided over by Marcel Dalio in a separate part (speaker, sculptor, fire chief, admiral), while the princess of the neighboring country of Miremie (Andrée Servilangas), in love with the Crogandie chancellor, pilots a plane to join him after drafting an explanatory letter to her father, who chases after her on horseback for the remainder of the film, never catching up with her.

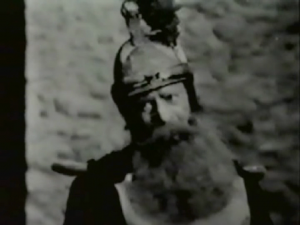

Meanwhile, at the Crogandie ceremonies, a group of staidly dressed young women who sing the national anthem (played by members of the Folies Bergères) break into a raunchy, leggy chorus line after the chancellor, periodically basted with confetti by a flunky and accompanied by a gramophone record, arrives in an open car. A bouquet of flowers presented to him by a woman is crushed by their embrace, then tossed away to be retrieved (in crisp editing) by a street cleaner. The unveiled statue of the chancellor shows him seated and simultaneously yawning and declaiming with arm extended while the veil itself is magically swallowed by the statue’s mouth; when the chancellor climbs up on the pedestal to retrieve the veil, he breaks into a yawn himself, at which point he and everyone else in Crogandie, after yawning, promptly goes to sleep. This includes the princess, whose plane crashes into a field. She quickly revives and goes off in search of her beloved, passing acres of inert bodies (shades of Paris qui dort [see below]) until she reaches the statue, removes the veil from the gaping mouth, and everyone in Crogandie wakes up.

Without noticing the princess, the crowd and chancellor move on to military formations of royal firemen (when the commander says, “At ease,” they all recline immediately into beach chairs, like wolves in a Tex Avery cartoon) and oddball gags involving a gas mask, a black fireman who doubles as fire-eater, and a decorated hero whose expansive beard blocks his decoration until shears are brought out to clear the view. The firemen perform a stately, prancing minuet that periodically turns into a frantic jog; a fake housefront for a firefighting demonstration blithely glides back and forth across a lawn. The chancellor is belated informed of the princess’s arrival just before his podium catches fire and he gets sprayed by a hose. Next comes a series of mishaps as a champagne bottle meant to launch a ship fails to break, after repeated tries, reducing the admiral to blubbering tears until a cannon fires the bottle straight through the side of the ship, causing it to sink. The chancellor and princess depart in the open car followed by a jubilant crowd while the chauffeur for no apparent reason – unless it’s pique about this international romance – proceeds to smash the radio studio. The End.

What we have here is clearly a series of provocations – as brittle as the vacuum cleaner and organ-tuning inside the church and the images of baby seals being clubbed to death in Le Diable, probablement (or the beheading that opens Lancelot du lac); as implicitly accusatory of the audience as the gaping crowd in the final shot of L’argent; and for me often as funny as the moment in Au hasard Balthazar when the police come upon Arnold in bed in his measly shack only to see him incongruously pull the blanket over his head. The fact that Bresson actually has a sense of humor is not supposed to be part of his “system,” any more than the constant play between sound and silence throughput his work is commonly thought of as play, except when Affaires publiques makes it obvious.

Everything, in fact, about Affaires publiques is fairly obvious except for the unmotivated ending, but in spite of the transcendental readings of his work, this tends to be true of most of his films: in the most literal sense, what you see and hear is what you get.

Perhaps the most Bressonian thing about this freakish and singular early effort, apart from its sheer physicality, is its anger combined with its conviction that the world is a fiendish place. This Sam Fullerish side of Bresson – complicated somewhat by Fuller’s tabloid sensibility, completely unshared by Bresson, which is often confused with his anger – immediately becomes apparent if one juxtaposes Balthazar with White Dog, or Le Diable with Shock Corridor. (I once asked Fuller if he’d seen Au hasard Balthazar; he hadn’t, but its theme and structure had once been described to him, and his immediate response to me was, “I like it.”)

The fact that Bresson’s middle-period films -– Diary of a Country Priest, A Man Escaped, Pickpocket, The Trial of Joan of Arc, Au hasard Balthazar, Mouchette –- propose central figures as models of purity, resourcefulness, and resilience, which did a great deal to produce the material for his allegedly all-encompassing “system,” doesn’t take us very far into the meanings of his five subsequent color films. Une femme douce is a transitional film and Lancelot of the Lake is the turning point into a more troubled and critical identification with his central characters, an evolution that for me seems equally marked by a change in religious conviction: whether or not Lancelot and L’argent actually qualify as atheist films, which is the way they strike me, they certainly don’t look for or expect to find the same kind of grace in their central characters. (Grace in Une femme douce is largely a matter of a piece of fabric fluttering to the ground when the title heroine leaps to her death; in Four Nights of a Dreamer, it’s the epiphany of the glorious and luminous bateau-mouche.)

And what about grace in Affaires publiques? The romantic subplot in the midst of all the pratfalls certainly doesn’t furnish it – the princess falls from the sky, not from grace, and ship sinks to the bottom of the ocean simply out of spite, not out of divine retribution. The coming together of the couple and the disintegration of state ceremony might be construed collectively as some sort of happy ending, but it’s strictly an anarchic sort of victory: the triumph of the raspberry, more Vigo than Lubitsch. If grace is vividly present in what I regard as Bresson’s two greatest films, A Man Escaped and Au hasard Balthazar, it’s also perhaps worth stressing that it’s more the French Occupation and the cruelty of mankind that bring it into being, make it matter, than the whims of divine fate. And in Affaires publiques there are no such extenuating circumstances. It’s simply a world of pompous impostures, prancing fools, and the unbridled impulses and human failings that expose them.