This article was originally published in Stop Smiling no. 27 (“Ode to the Midwest”) in 2006. It’s also reprinted in my collection Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia. — J.R.

Kim Novak as Midwestern Independent

It’s possible that the star we know as Kim Novak was partially the invention of Columbia Pictures —- conceived, as the Canadian critic Richard Lippe puts it, both as a rival/spinoff of Marilyn Monroe and as a replacement for the reigning but at that point aging Rita Hayworth. At least this was the favored cover story of Columbia studio head Harry Cohn, whom Time magazine famously quoted in 1957 as saying, “If you wanna bring me your wife and your aunt, we’ll do the same for them.” It was also the treasured conceit of the American press at the time, which was all too eager to heap scorn on Novak for presuming to act — just as they were already gleefully deriding Monroe for presuming to think. But Monroe, as we know today, was considerably smarter than most or all of the columnists who wrote about her. And Kim Novak — a major star if not a major actress — had something to offer that was a far cry from updated Hayworth or imitation Monroe (even if the latter was precisely what Columbia attempted to do with her in one of her first screen appearances, in the 1954 Judy Holliday vehicle Phffft!). In point of fact, Novak was more beautiful than either actress, yet paradoxically she was also less of a fantasy. Marilyn Monroe was plainly a comic-strip figure and a fantasy wish-fulfillment that simultaneously converted all the men in her orbit into both fathers and infants, whereas Hayworth apparently lived up to her own self-characterization: “Men go to bed with Gilda but they wake up with me.” But Novak was real from the get-go, and it’s tempting to think that her humble Midwestern origins had something to do with her reality.

Born Marilyn Pauline Novak in Chicago in 1933 — the daughter of a Slavic transit clerk for the railroad (her father) and a former teacher (her mother) —- she started off in advertising, as “Miss Deepfreeze,” touring the country while selling refrigerators. She became a movie star only after she started working as a model in Los Angeles, landing first an uncredited bit in The French Line (1954), then a full part as a gangster’s moll in Pushover later the same year. (Her director on that film, Richard Quine, later became her fiancé, though they never married, and he wound up directing her in three more features —– Bell, Book and Candle, Strangers When we Meet, and The Notorious Landlady. Her other most frequent director, George Sidney, projected a brassy vulgarity that was more suitable for an imperturbable powerhouse like Esther Williams than for a delicate creature like Novak, and she survived the encounter best during their first picture together, The Eddy Duchin Story.)

Of course it wasn’t just the working-class and Midwestern aspects of Novak’s background that registered in the public’s mind. She was also Marjorie Oelrichs in The Eddy Duchin Story(1956), a well-to-do interior decorator in who gets Boston pianist Duchin (Tyrone Power) his first New York gig and eventually marries him. She was Linda English from Albuquerque in Sidney’s Pal Joey (1957), struggling to make it as a vocalist in a San Francisco nightclub. And in Quine’s Bell, Book and Candle (1958), she was Gillian Holroyd, a classy bohemian witch in Manhattan. Furthermore, she was regally upscale as Madeleine Elster, one of the two San Francisco personas she incarnated in Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958).

Later on, she would play Betty Preisser in Paddy Chayefsky and Delbert Mann’s Middle of the Night (1959), the mistress of a much older New York garment manufacturer (Fredric March); Maggie Gault in Evan Hunter and Richard Quine’s Strangers When We Meet (1960) — a sexually and romantically frustrated Beverly Hills housewife and mother who becomes involved with a neighbor, a married architect and father (Kirk Douglas); and Polly the Pistol in Billy Wilder’s Kiss Me, Stupid (1964), a prostitute working out of her trailer in Climax, Nevada. But in spite of such diversity in terms of class and geography, it was arguably her modest Midwestern roots — as Madge Owens (in a small town in Kansas) in Picnic (1955), as Molly (in the Polish slums of Chicago) in The Man with the Golden Arm (1955), and as the title heroine in Sidney’s Jeanne Eagels (1957), who starts out as a Kansas City waitress — that were most operative in establishing her overall screen reality.

Later on, she would play Betty Preisser in Paddy Chayefsky and Delbert Mann’s Middle of the Night (1959), the mistress of a much older New York garment manufacturer (Fredric March); Maggie Gault in Evan Hunter and Richard Quine’s Strangers When We Meet (1960) — a sexually and romantically frustrated Beverly Hills housewife and mother who becomes involved with a neighbor, a married architect and father (Kirk Douglas); and Polly the Pistol in Billy Wilder’s Kiss Me, Stupid (1964), a prostitute working out of her trailer in Climax, Nevada. But in spite of such diversity in terms of class and geography, it was arguably her modest Midwestern roots — as Madge Owens (in a small town in Kansas) in Picnic (1955), as Molly (in the Polish slums of Chicago) in The Man with the Golden Arm (1955), and as the title heroine in Sidney’s Jeanne Eagels (1957), who starts out as a Kansas City waitress — that were most operative in establishing her overall screen reality.

Even Judy Barton, the working-class character Novak plays in Vertigo, has the effect of making Madeleine Elster, her glitzy predecessor, seem more like a manufactured illusion —- or more specifically, an image that the obsessed hero (James Stewart) calls on Judy to recreate. And even though Madge in Picnic is middle-class, the destiny she opts for at the movie’s end is distinctly downscale when she boards a bus for Tulsa — before James Wong Howe’s airborne CinemaScope camera rapturously races ahead of her to connect her epic trajectory to that of Hal Carter (William Holden), her working-class beloved, on a train bound for the same destination. And even more telling than her character’s class, real or adopted, in either Vertigo or Picnic, is her seeming independence as a solitary figure.

Even Judy Barton, the working-class character Novak plays in Vertigo, has the effect of making Madeleine Elster, her glitzy predecessor, seem more like a manufactured illusion —- or more specifically, an image that the obsessed hero (James Stewart) calls on Judy to recreate. And even though Madge in Picnic is middle-class, the destiny she opts for at the movie’s end is distinctly downscale when she boards a bus for Tulsa — before James Wong Howe’s airborne CinemaScope camera rapturously races ahead of her to connect her epic trajectory to that of Hal Carter (William Holden), her working-class beloved, on a train bound for the same destination. And even more telling than her character’s class, real or adopted, in either Vertigo or Picnic, is her seeming independence as a solitary figure.

Maybe it was Novak’s beauty and her acute awareness of it that made her fragile, and perhaps it was her fragility that made her real. “Mom, what good is it just to be pretty?” she says as Madge to Betty Fields in Picnic. This was her first big movie role, and presumably the line came from playwright William Inge. But it appeared to come from the actress as well as the character she was playing — expressing what always seemed to make Kim Novak less than wholly delighted about the burden of being a movie star and a glamorous myth, when she’d rather chow down with the rest of us. It was the kind of ambivalence that worked against the obsessive career-building of a Monroe, so that her fame peaked early on, and was already fading fairly rapidly after about a decade. Much as Novak’s husky voice seemed to contradict or at least complicate the hyperbolic femininity she was supposed to project, her down-home earthiness often wound up undercutting some of her obligatory studio baggage as a glamor queen.

Maybe it was Novak’s beauty and her acute awareness of it that made her fragile, and perhaps it was her fragility that made her real. “Mom, what good is it just to be pretty?” she says as Madge to Betty Fields in Picnic. This was her first big movie role, and presumably the line came from playwright William Inge. But it appeared to come from the actress as well as the character she was playing — expressing what always seemed to make Kim Novak less than wholly delighted about the burden of being a movie star and a glamorous myth, when she’d rather chow down with the rest of us. It was the kind of ambivalence that worked against the obsessive career-building of a Monroe, so that her fame peaked early on, and was already fading fairly rapidly after about a decade. Much as Novak’s husky voice seemed to contradict or at least complicate the hyperbolic femininity she was supposed to project, her down-home earthiness often wound up undercutting some of her obligatory studio baggage as a glamor queen.  For all of Cohn’s braggadocio, Columbia Pictures often had a confused sense of how to use her to best advantage. Perhaps its worst idea was to miscast her as a variant of Sunset Boulevard’s Norma Desmond in Jeanne Eagels, a downbeat black and white biopic about the famous 1920s stage actress who died of a drug overdose —- a vehicle that was presumably meant to show off Novak’s acting chops. The film begins promisingly with Eagels arriving at a Kansas City carnival to enter a beauty contest overseen by Jeff Chandler, who soon thereafter becomes her boss and lover. It’s only after Eagels’ driving ambition to become a stage actress transforms her into Chandler’s boss that the film turns sour and its antifeminist agenda becomes fully apparent.

For all of Cohn’s braggadocio, Columbia Pictures often had a confused sense of how to use her to best advantage. Perhaps its worst idea was to miscast her as a variant of Sunset Boulevard’s Norma Desmond in Jeanne Eagels, a downbeat black and white biopic about the famous 1920s stage actress who died of a drug overdose —- a vehicle that was presumably meant to show off Novak’s acting chops. The film begins promisingly with Eagels arriving at a Kansas City carnival to enter a beauty contest overseen by Jeff Chandler, who soon thereafter becomes her boss and lover. It’s only after Eagels’ driving ambition to become a stage actress transforms her into Chandler’s boss that the film turns sour and its antifeminist agenda becomes fully apparent.

It’s entirely to Novak’s credit that she can’t play hard and ruthless the way the film wants her to. Demonic divas aren’t part of her repertoire -— as director Robert Aldrich must have discovered to his regret when he miscast her in a double role in The Legend of Lylah Claire (1968), as both the deceased title diva and Elsa Brinkmann, the starlet who’s hired to play her onscreen. But Novak’s honorable failure in Jeanne Eagels still derails both the story and Sidney’s leering direction (which also brutalizes her in Pal Joey when her masochistic character dutifully performs a nightclub strip to please Frank Sinatra’s Joey); at best she can portray a tormented diva and do a few drunk scenes. The film wants to show her as a victim of her own hubris, but all she can handle is the victim part, without any clear sense of what’s victimizing her — unless it’s her desire to be famous. The film pretends to see her downfall as tragic, yet it almost seems to gloat over the ironic titles of some of her stage vehicles, such as Careless Lady and Forever Young.

Far more persuasive are the roles in which Novak’s character comes across as loyally devoted to the movie’s hero without ever sacrificing some of her spiky independence, as in her three pictures preceding Jeanne Eagels (Picnic, The Man with the Golden Arm, The Eddy Duchin Story) — and in her second and third outings with Quine, both underrated, Bell, Book and Candle and Strangers When We Meet, where her independent spirit and her libido almost seem to be running neck in neck. In all five of these movies, she’s rebellious and even somewhat courageous —- not quite the compliant pussycat that the mythic aura of her beauty and the sexism of 50s Hollywood sometimes make her out to be —- even though Maggie Gault, her Emma Bovaryish character in Strangers, is sometimes in denial about her own passion. It also must be conceded that thanks to this character’s repressed and sexist milieu, the only visible form of independence or rebellion available to her is in fact her adultery, and the only visible form of courage is the stoicism with which she faces the loss of her lover.

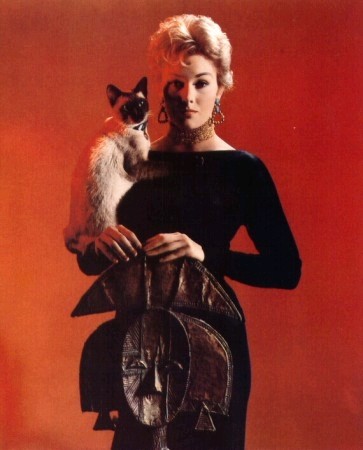

It’s a tribute to Novak that she can make a tragic heroine rather than a pathetic victim out of Maggie, largely because she’s so adept at making us experience the full fury of her blocked desires. In fact, the projection of her characters’ sexual desires is a near-constant in her work. “Why don’t you give me him for Christmas?” she purrs to her Siamese cat, Piewacket, in the opening scene of Bell, Book and Candle, referring to her upstairs neighbor (James Stewart), whom she’s just met for the first time. French film critic Bernard Eisenschitz aptly describes this charmed and charming movie as “the optimistic version of Vertigo” (made the same year, with the same costar), and James Wong Howe lights and frames her here with the same reverence that he brought to her beauty in Picnic. By way of contrast, her sexiness and her softness-within-firmness as “Molly-o,” the Madonna-like savior of heroin addict and jazz drummer Frankie Machine (Frank Sinatra) in The Man with the Golden Arm, is like a triumph of neorealism in the midst of director Otto Preminger’s doom-ridden, set-bound expressionism. She’s trapped like Frankie, but she also comes across as more independent than anyone else in the picture, and Novak’s funkiness collides with Sinatra’s to create a volatile, smoky brew.