Written in 2013 for a 2019 Taschen publication. — J.R.

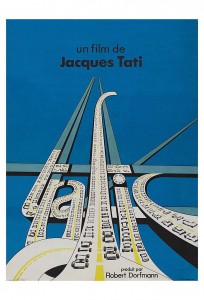

Trafic

1. The Reluctant Return of Monsieur Hulot

“On the basis of my intentions, Trafic could have been shot before PlayTime,” Tati said to me in late 1972, when I met him for the first time, only a couple of weeks before Trafic opened in the U.S. And the reason why he felt that way about his fifth feature was directly related to his most famous character, Monsieur Hulot.

As far as his own intentions were concerned, Hulot was a character he had invented strictly for the purposes of a single feature, Les Vacances de Monsieur Hulot. The main reason why he reappeared in Tati’s next three features was public demand. If it had been left up to Tati and his own inclinations, Hulot would have vanished after that one film, but the audience’s affection for that figure wouldn’t allow it; Hulot, after all, was better known and more familiar to the public than Tati himself was. So his creator reluctantly brought him back in Mon Oncle, and even gave him the title role a second time. But on this second occasion, one might say that Hulot existed again only as a function and contrast to the other characters — an eccentric relative of the Arpel family, and in some ways an alternative father figure for a little boy. And when it came to PlayTime, Tati made a concerted effort to show how unnecessary and inessential Hulot was by creating a whole cast of doppelgängers — characters who first appeared from a certain distance to be Hulot because of the way they dressed and the umbrella they often carried but who turned out to be quite different — different in age or in nationality or even in race and ethnicity. (One of the Hulots, for instance, turns out to be a black American jazz musician.) This was a way of both teasing the audience and, more hopefully, guiding them in a different direction.

By treating M. Hulot as superfluous, Tati hoped to be paving a path that would allow him to get rid of this character for good. But the huge financial failure of PlayTime that drove him into bankruptcy not only undermined this possibility; it also brought Tati to the sad realization that in order to attempt to recoup his losses, he would have to bring back Hulot again, and this time in a more prominent and conventional manner — so that for the first and only time, Hulot appears in the credits before the title, and under his Anglo-American name: “Mr. Hulot dans Trafic.” And for the first time, he would also have a professional identity, appearing as a car designer. And Tati made him the designer of an absurdly multifunctional camper that he and others try in vain to transport from Paris to an Amsterdam auto show. In short, his bankability as an actor — more specifically, as one of his roles as an actor — had to supersede his ambitions as a director.

The fact that we never even learned Hulot’s first name over the course of the four features he appeared in is surely significant. As Tati’s shrewder critics were quick to point out, Hulot was something closer to the carrier of certain quirky qualities that his creator valued than he was to a character in any ordinary or psychological sense of that term. (André Bazin, writing after only the first of his film appearances: “Il peut être personnellement absent des gags les plus comiques, car M. Hulot n’est que l’incarnation métaphysique d’un désordre que se perpétue longtemps après son passage.” [“He can be absent from the funniest gags because he is only the metaphysical embodiment of a state of disorder that will continue long after he has left the scene.”][1]) In his own personality, it’s important to stress that Tati was nothing like Hulot — graceful where Hulot was clumsy, demonstrative where Hulot was shy, gregarious where Hulot tended to be solitary, and observant where Hulot (especially in Les Vacances de Monsieur Hulot and Mon Oncle) tends to be oblivious to much of what’s happening around him.

2. Origins and Vicissitudes

Trafic stems from many separate sources apart from a commercially motivated desire to bring back Hulot in a more prominent and central role (see above). In the early 60s, Tati had discovered a brilliant comic short by the Dutch filmmaker Bert Haanstra called Zoo (1962), which he wound up distributing and showing along with the recently retooled Jour de fête. Haanstra by then was a figure with an international reputation (his documentary short Glass, filmed in a glass factory, had won an Academy Award four years earlier), and Zoo — which cuts between documentary glimpses of visitors in a zoo watching animals and animals in the same zoo watching visitors, all matched cleverly to sprightly jazz, and with many ingenious rhyme effects — clearly struck a responsive chord for Tati in its parallels with his own quirky comic observations. (The visual ambiguities were also somewhat similar; as Marc Dondey put it in his own description, “Est-ce l’enfant qui imite la chimpanzé, ou bien l’inverse? “Is it the child imitating the chimpanzee or vice versa?”)[2]

The two men became friends and spoke about collaborating on a future project, and shortly after the completion of PlayTime, this evolved first (as reported by Tati biographer David Bellos) into a plan to make twenty 20-minute television shows featuring Hulot, and then, more concretely, to make a feature about cars and drivers (a theme Tati had been contemplating for some time) — a Dutch-French coproduction featuring Hulot, with Haanstra as director and a script to be co-written by himself and Tati, to be shot in Holland with a Dutch crew. Shortly after this, Tati’s family went on a ten-day cruise in the Netherlands with the Haanstra family on the latter’s boat, where they discussed the film further, and a commissioned set of forty-three sketches of cars and twenty-eight cartoon sketches of comic incidents was produced by late August 1968. By the end of that year, Tati reconfigured the project as a Swedish-Dutch-French coproduction, with Svensk Filmindustri furnishing the first $200,000; this required a script of some sort, and Tati wrote a six-page outline that later grew into a 93-page script called Yes, Mr. Hulot.

Meanwhile, on the basis of the six-page outline, Haanstra began shooting material the following spring, with much input from Tati (including some directing) — in a vast, empty hall (shot at a hangar in Amsterdam’s Schipohl airport), at an automobile show, and a montage of candid-camera glimpses of drivers picking their noses during a traffic jam that comes close to matching the style of Zoo, all of which wound up in some form in the final film. (Haanstra later also shot some material at the DAF car plant, presumably used in the credits sequence) But before long, it became clear to both men that a true and equal collaboration wouldn’t be possible, and, after much confusion, exacerbated by Tati’s financial difficulties deriving from PlayTime, Haanstra agreed to back out of the project by the end of August 1969. But by then, Svensk Filmindustri had also withdrawn from the project, and in December, Tati’s own bankrupted company, Specta Films, had to be put up for sale. By this time, Yes, Mr. Hulot had been retitled Trafic, but shooting the remainder of the picture would have to await further financing sources, and this eventually came from Silenia Cinematografica in Rome, Italy, which had recently coproduced Costa-Gavras’ L’aveu, Luis Buñuel’s Tristana, and Jean-Pierre Melville’s Le Cercle rouge. Towards the end of shooting, Tati was also helped out by a Swedish crew that in theory was only shooting a “making of” documentary about Trafic, but also wound up furnishing some of the film stock and technicians when other resources were exhausted.

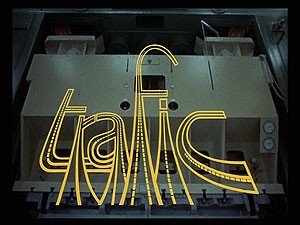

In short, one might say that the trajectory of the film’s plot — a journey from A to B, interrupted by countless delays and mishaps, some of which virtually overtook and redefined the action — was reflected in its making, and a good two years were to pass from the start of shooting and the film’s opening. At a new theater on the Champs Elysées, where the premiere took place, Tati had an elaborate sign created which functioned like a virtual manifesto for how he wanted the film to work. It consisted of little more than the words of the title (cleverly styled to resemble a freeway) superimposed over a huge mirror that reflected the cars driving past as well as the pedestrians on the sidewalk.

3. Trafic: Major or Minor?

Although most critics have regarded Trafic as a relatively minor work in Tati’s oeuvre, one of the most perceptive, the late Jean-André Fieschi, regarded it as one of his three masterpieces, along with Les Vacances de M. Hulot and PlayTime.[3] And one formal aspect of the film that Fieschi valued especially was a kind of dialectical pattern he saw between everything in the film that was carefully pre-planned and designed, even programmed, and everything that was left up to chance, circumstance, and improvisation; the dialectic between fiction and non-fiction in the film would be a somewhat different way of making this sort of distinction, but we might also distinguish more complexly between documentary (shots of drivers who were unaware that they were being filmed, or the shots of cars being manufactured that appear behind the opening credits), fantasy (elaborate gags that could only be invented and staged and could never be found in the real world, such as many of the publicist Maria’s instantaneous costume changes and some of the immediate results of the climactic traffic accident), recreated versions of things that Tati observed, and satirical exaggerations of other things that he observed.

It might be added that, in many cases, distinguishing between these various kinds of material is not nearly as simple or as easy as it might at first appear to be. Even though we know that the montage sequence that cuts between various drivers in cars who are picking their noses mainly or exclusively comes from documentary, “candid-camera” footage that was shot by Bert Haanstra during the early stages of the production, how sure can we be that the shot including two separate nose-pickers — the second one driving a car that pulls up in the foreground, alongside the first one — wasn’t contrived in some way? And even if we decide (or can establish) that all of the shots in this sequence were caught without any direction of the participants, how much of a role does editing play in joining these shots together in a highly rhythmic and musical pattern, making their overall effect highly programmed? And when we get another montage sequence near the very end of the film in which the movements of windshield wipers are brilliantly counterpointed with the gestures of drivers and front-seat passengers, is it possible that one of these could have been caught strictly by chance, thus inspiring Tati to invent or stage all the others? The film’s uncommon achievement, in other words, at least on many occasions, is to blend together fictional and non-fictional elements into a seamless whole, demonstrating the Tati’s genius in organizing his materials could be every bit as adroit as his genius for either finding or inventing them. All three processes are intricately interwoven in the film as a whole.

4. Tati and Cars

When I asked Tati in 1971 what his attitude was towards cars, he replied, “Well, first of all, they change the personality of people. Take a very nice gentleman whom you’ll meet in a bar: as soon as he gets in his car, he changes absolutely; he has to be very strong not to change. Secondly, the more the engineers work for us, the less we have to do when we drive a car. . . before, people participated in the driving; they knew by the sound of the motor how to change gears—rmrmrm, into second, and so forth. You participated, and you had to be a good driver. Now, with the new American car, it doesn’t make any difference whether you’re a bad or good driver. What they call comfort and new techniques have become so exaggerated that I tried to create a car that was absolutely ridiculous, where you can take a shower, make coffee, shave — but it’s not practical at all, it’s the worst possible car to take on a holiday, because it brings you so many problems. And when you become so remote from what’s designed for you, the human connections between people start to go — like with the police in the film. I’m always — in each shot, each moment — trying to defend the simple man, who tries to fix something with his hands.”*

*It’s also worth recalling that Tati himself suffered a serious car accident in May 1955, a little over a year before he began shooting Mon Oncle, and that experience likely played a significant role in inspiring the massive highway accident in Trafic, as probably did an auto accident of his wife on another occasion

5. Echoes of earlier Tati features

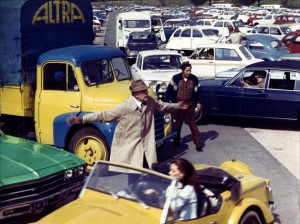

Although made much more quickly and inexpensively than PlayTime, Trafic occasionally recalls Tati’s previous feature in a few of its details. It even has one of the same actors, apart from Tati himself; François Maisongrosse, who plays a salesman for Altra, the fictional car company in Trafic that most of the characters work for, also played one of the waiters at the Royal Garden in PlayTime — the one who gets secretly drunk on wine over the course of the evening, as we can intuit from his boisterous laughter. The opening sequence, set in the huge empty hangar in Amsterdam where the international car show will be held, recalls PlayTime in the way it frames characters in extreme long shot stepping over imperceptible wires while they walk around, being dwarfed by their enormous surroundings. One might add that the car show itself, once it’s up and running, recalls the gadget exhibition that Hulot and other characters wander through in the daytime segments of PlayTime.

Both films base much of their comedy on the various disasters that can arise from rigid over-planning and various kinds of stiff and/or thoughtless behavior associated with this sort of micromanagement, and in Trafic much of this critique is focused on the impatience of Maria (Maria Kimberley), the brisk and short-tempered American public-relations representative who works for Altra. (Would it be excessive to speculate that the initial lack of American distribution for PlayTime, which lead directly to Tati’s bankruptcy, might have played some role in the treatment of certain American traits by Tati with less affection than they received in PlayTime? The “franglais” titles of both films suggests that what America signifies in both films is, at the very least, a complicated matter.) The sharp right-angle she takes when she enters the film, at Altra’s Paris headquarters, already links her in some ways to the over-regulated patterns of movement associated with PlayTime’s skyscrapers, and the looser, freer, and more relaxed behavior that she shows at the end of the film, after switching her attire from designer chic to blue jeans, points to an overall moral education that is similar in many ways to the various social developments charted in the earlier feature. And most of that moral education occurs at the idyllic site of the Flemish garage beside a canal where she and a couple of other Altra employees, including Hulot, find that they have to spend the night. And the main guru in this education is the burly, good-natured and laid-back guy who runs the garage, played by Tony Knepper, whose role in the proceedings closely parallels that of the free-spending American, Schultz (Billy Kearns), in PlayTime. Finally, the tender complicity that develops by the end between Hulot and Maria, when she becomes Hulot’s escort in the rain — culminating in the bittersweet melancholy of the final shot, which seems to view humanity itself as a bemused tribe, lost in a senseless labyrinth — echoes in some ways the warmth between Hulot and Barbara, an American tourist, near the end of PlayTime.

The satire concerning the “camping car” that Hulot and his fellow Alta employees are transporting in a truck to the car show in Amsterdam, tricked out with an endless number of absurd built-in appliances, gadgets, and conveniences — everything from an electric razor that pops out from behind the horn on the steering wheel to a barbecue grill located inside the front bumper, along with a miniature kitchen, a shower, a tent, a TV, and various clip-on lights, most of them ironically demonstrated to Dutch customs rather than the public in Amsterdam — clearly echo some of the “up-to-date” appliances in the Arpel mansion in Mon Oncle, with a similar aura of unnecessary social pretension. (By the same token, we can readily see certain links between the fake evocations of nature in the Arpels’ rock garden with its fish fountain and the fake sections of the trunks of birch trees accompanied by taped bird songs in the Altra section of the Amsterdam Car Show.) Furthermore, Trafic clearly continues Tati’s concern about the effects of an escalating car culture overtaking the planet, which was already apparent in his third feature. More generally, the intimidating effect of a newsreel about high-speed, high-tech mail delivery in the United States on a French village postman in Jour de fête is paralleled in some respects by the impact on ordinary French and Dutch workers of watching the first moon landing, Apollo 11, on TV — only in this case it’s the slowness of what they’re watching rather than the speed that impresses them, which prompts them to parody the slow-motion movements that they see onscreen. When I asked Tati about this in my 1971 interview with him, he said, “To copy and make a joke about what they see on television, the people start to work more slowly. For them, the moon flight isn’t a great achievement; in relation to their private lives, it’s a flop.” Once again, it seems that part of the implication about technology in Jour de fête, Mon Oncle, PlayTime, and Trafic alike is that what’s regarded by some as a landmark and step forward for “mankind” might actually be irrelevant to the lives of ordinary workers, even if it’s commonly regarded as a challenge and something to be sought after as well as valued.

6. Peace Beside a Canal

Harking back to the bucolic pleasures that were prominent in Tati’s first two features, Trafic posits aimless and haphazard drift as a meaningful alternative to capitalist compulsiveness. This helps to explain why documentary — including much of the footage of motorists Tati took over from his initial codirector, Haanstra — becomes a part of his artistic palette here, at the same time that hippies are welcomed into his social universe. Both become even more prominent in Parade.

The critic Michel Chion has written that Trafic recounts “un trajet entre deux lieux don’t aucun n’a d’existence propre.…Paris est une sorte d’autoroute et un coin de place entr’aperçu; Amsterdam un palais d’exposition. Plus rien n’existe que le trajet.” (“…a journey between two places, neither of which really exists….Paris is a motorway exit and a corner of a square fleetingly glimpsed; Amsterdam is reduced to an exhibition hall. Only the journey is real.”)[4] To which one might add that the only place in Trafic that feels very real is a Dutch garage beside a canal where nothing much happens, apart from some casual repair work, and a rather malicious if well-developed gag about a hippie coat made to resemble Maria’s equally fluffy dog — a prank pulled by some local hippies. The latter prank is a response to Maria almost running over another dog herself; more generally, it occurs after many other signs of her impatience — and the fact that she typically makes sharp right-angle turns when she walks, which already arguably makes her a little suspect in Tati’s eyes — at least according to the geometrical ethics of PlayTime, where lackadaisical, accidental curves are signs of humanity triumphing over a certain regimentation.

This is also the stretch when Hulot spills ink on Maria’s sunglasses and, after she furiously polishes several portions of the camper (briefly evoking the anxiety of Mme. Arpel polishing her husband’s car in Mon Oncle), she laughs with delight when she discovers her own mistake, thus proving both that disorder exists in the eye of the beholder and that sometimes it’s something to be cherished, not merely something to be scorned and avoided. Trafic might be said to take an easy breath here, entering a zone of reflection amidst all the rush, and so do we.

[1] André Bazin, “M. Hulot el le temps,” Qu’est-ce que le cinéma?, , vol. 1, Paris: Éditions du Cerf, 1969, p. ?, and What is Cinema?, translated by Timothy Barnard, Montreal: Caboose, 2009, p. 40.

[2] Marc Dondey, Tati, Paris: Ramsay, 1993, p. 225.

[3] Jean-André Fieschi, “Jacques Tati,” translated by Michael Graham, Cinema: A Critical Dictionary, vol. 2, edited by Richard Roud, London: Martin Secker & Warburg, 1980, p. 1001.

[4]Michel Chion, Jacques Tati, Paris: Cahiers du Cinéma (Collection “Auteurs”), 1987, p. 82, and The Films of Jacques Tati, translated by Monique Viñas, Patrick Williamson, and Antonio D’Alfonso, Toronto/New York/Lancaster: Guernica, 1997, p. 114.