From the online Moving Image Source (July 20, 2011), — J.R

Everybody has their own Laurel and Hardy. A miniature Laurel and Hardy, one on each shoulder. Your little Oliver Hardy bawls you out -– he says, “Well, this is a fine mess you’ve gotten us into.” And your little Stan Laurel gets all weepy -– “Oh, Ollie, I couldn’t help it, I’m sorry, I did the best I could….”

— Groucho Marx on LSD

Living in a garbage can be a lot of fun….

Life is always equal in the can….

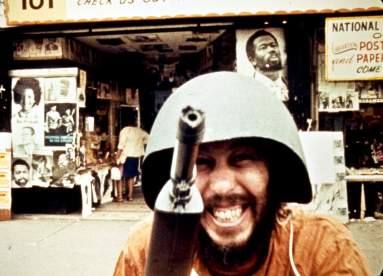

— the first and last lines of Skidoo’s Garbage Can Ballet

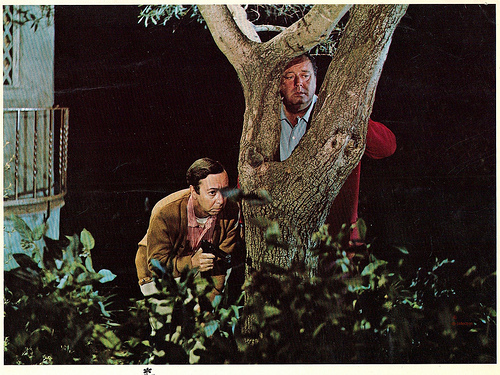

Seeing works of art, including films, in terms of success or failure, smash or flop, can be a form of tyranny, a limiting of options — not to mention a recipe for boredom, especially if one has no monetary stake in the outcome, which is true in most cases. So to say that Otto Preminger’s Skidoo –- which has finally become available on a letterboxed DVD, released by Olive Films -– failed at the boxoffice in 1968 and fails today, as it failed 43 years ago, as a lighthearted comedy, while certainly accurate, may not be the most helpful thing to say about it. Read more