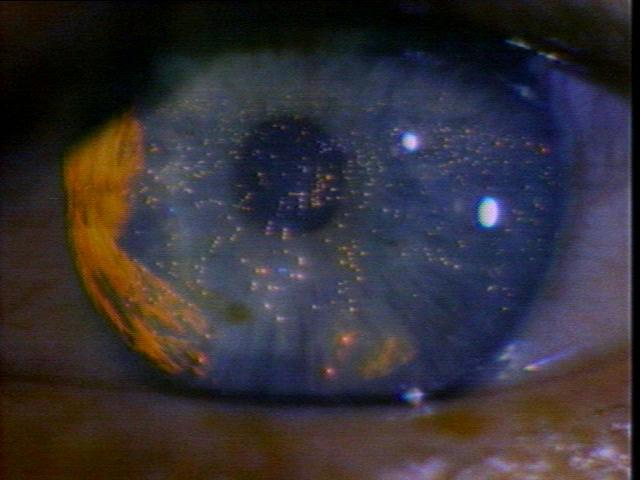

Here is an essay about Ebahim Golestan that appeared in the Chicago Reader on May 3, 2007, along with capsule reviews of three Golestan programs that showed in Chicago the same week. I posted these shortly after reseeing the remarkable and criminally neglected Brick and Mirror at the Edinburgh International Film Festival, with Golestan, now in his early 90s, both present and eloquent in speaking about his work. Note: if you hit the subtitled still below, you can see a very brief silent clip from Brick and Mirror. — J.R.

Brick and Mirror

A high point of Iran’s first new wave, this 1964 masterpiece by Ebrahim Golestan takes its title from the classical Persian poet Attaar, who wrote, “What the old can see in a mud brick, youth can see in a mirror.” The philosophical implications of this are fully apparent in Golestan’s tale of a young man who finds a baby girl in his cab and spends a night with his girlfriend debating what to do with the infant. Though this black-and-white ‘Scope film superficially resembles Italian neorealism, especially in its indelible look at Tehran street life and nightlife in the 60s, its spirit is a mix of Dostoyevsky and expressionism: minor characters periodically step forward to deliver anguished soliloquies, contributing to an overall lament both physical and metaphysical. Read more