From Monthly Film Bulletin, June 1976 (Vol. 43, No. 509). — J.R.

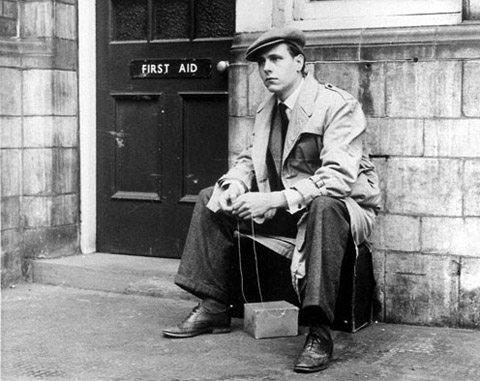

Hollywood Cowboy

U.S.A., 1975

Director: Howard Zieff

Cert–A. dist–ClC. p.c–MGM. A Bill/Zieff production. p–Tony Bill. p. manager–Clark L. Paylow. asst. d–Jack B. Bernstein, Alan Brimfleld. sc–Rob Thompson. ph–Mario Tosi. col–Metrocolor. ed–Edward Warschilka. a.d–Robert Luthardt. set dec–Charles R. Pierce. m-Ken Lauber. m. sup–Harry V. Lojewski. special musical artists–Nick Lucas, Roger Patterson, Merle Travis. cost–Patrick Cummings. choreo--Sylvia Lewis. Titles/opticals–MGM. sd–Jerry Jost, Harry W. Tetrick. sd. effects–John P. Riordan. l.p–Jeff Bridges (Lewis Tater), Blythe Danner (Miss Trout), Andy Griffith (Howard Pike), Donald Pleasence (A. I. Nietz), Alan Arkin (Kessler), Richard B. Shull (Stout Crook), Herbert Edelman (Polo), Alex Rocco (Earl), Frank Cady (Pa Tater), Anthony James (Lean Crook), Burton Gilliam (Lester), Matt Clark (Jackson), Candy Azzata (Waitress), Thayer David (Bank Manager), Marie Windsor (Woman at Nevada Hotel), Anthony Holland (Guest at Beach Party), Dub Taylor (Nevada Ticket Agent), Raymond Guth (Wally), Wayne Storm (Zyle), Herman Poppe (Lowell), William Christopher (Bank Teller), Jane Dulo (Mrs. Read more