From Film Comment (September-October 2011). — J.R.

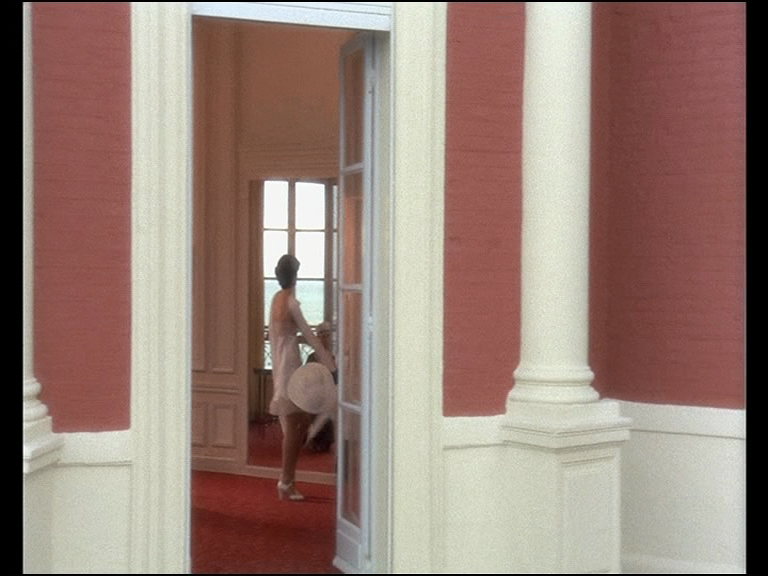

Recalling the incident in Turin that reportedly occasioned Friedrich Nietzsche’s final breakdown into madness — his weeping and embracing a cab horse that was being beaten by its driver for refusing to budge — Béla Tarr’s regular screenwriter, novelist László Krasznahorkai, has noted that no one seems to know or ask what happened to the horse. But The Turin Horse is only nominally concerned with this riddle. It’s more concerned with the horse’s driver and his grown daughter, who live in a remote stone hut without electricity, subsisting on an exclusive diet of potatoes and palinka (Hungarian fruit brandy) while a perpetual storm rages outside, then arbitrarily subsides, over a carefully delineated six days. Their abject life remains fixed by a few infernal routines, such as dressing, undressing, drawing water from a well, or looking out the window. (One exterior shot of the daughter doing just that towards the end of the film will haunt me the rest of my life). What passes for plot gradually becomes even more minimal by the driver’s horse first refusing to pull the wagon, then refusing to eat. Read more