Yesterday, while reseeing François Truffaut’s Fahrenheit 451 for the first time in years at the Gene Siskel Film Center, just before doing a Skype interview with Ray Bradbury in California along with Bradbury’s biographer, Sam Weller, I was struck for the first time how different Truffaut’s and Bradbury’s historical groundings were. Bradbury’s novel, first published in the early 50s, clearly reflected the Cold War, whereas Truffaut’s English-language film (his only one) of 1966, two years before his secret discovery via detectives that his father had been a Jewish dentist, seems largely informed by his childhood experience of the German occupation of France, which he would only depict directly 14 years later, in The Last Metro.

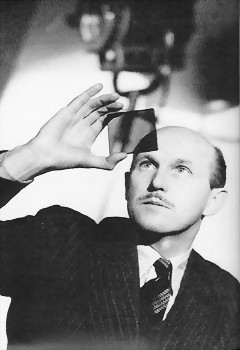

The most surprising aspect of this for me is that I never thought of it earlier — but it becomes especially clear during the scene in which Montag (Oskar Werner) and Clarisse (Julie Christie) in a cafe secretly spy through a window an informer pausing before mailing his malicious report on a neighbor to the police/fire department (which in the world of Fahrenheit 451 is the same thing), meanwhile making comments on his behavior (some of which are reproduced below in the subtitles). It also seems evident in the number of old, early-40s books that one sees being burned in the many book-burning sequences, as well as in the dingy scenes set in old-fashioned basements, attics, etc. Read more