From the Chicago Reader (March 31, 2006). — J.R.

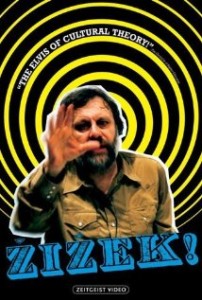

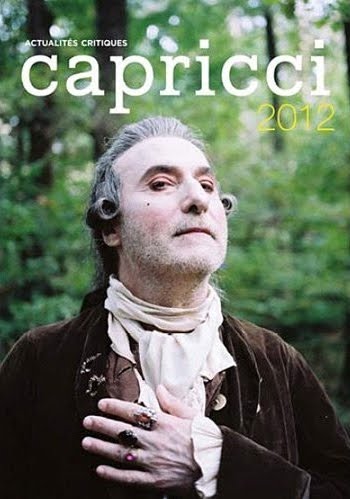

I’m almost tempted to say that making me popular is a resistance against taking me serious, says Slavoj Zizek in this entertaining 2005 portrait of the Slovene cultural theorist and academic rock star. It’s a characteristic utterance, and his charisma is such that the meaning registers despite the faulty grammar. Whether he’s ruminating in his Ljubljana flat, speaking at the University of Buenos Aires, fleeing autograph hounds, running for president of Slovenia (in 1990), defining ideology, or staging his own mock suicide, his frenetic and lucid manner is neatly captured by the jazzy style of director Astra Taylor. In English and subtitled Slovene. 71 min. (JR)