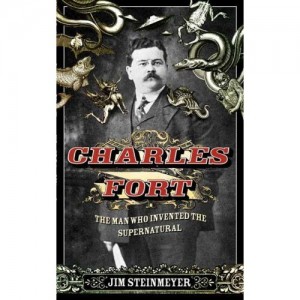

TEX AVERY: A UNIQUE LEGACY (1942-1955) by Floriane Place-Verghnes (Eastleigh, UK: John Libbey Publishing), 2006, 214 pp.

I love the last line in Dr. Place-Verghnes’ Acknowledgments -– a tactful understatement which demonstrates both that she wears her academic armor lightly and that she’s temperamentally suited to dealing with someone like Avery: “I reserve a particular sentiment for Warner Brothers Inc., without whom and their point-blank refusal to grant copyright authorisation, this volume would have contained multiple images from Tex Avery and others’ cartoons in support of the textual content.” (Actually, she does cheat a tad by reproducing or at least imitating a classic Avery image on the book’s cover–two giant bulging eyeballs as they appear in one of the Wolf cartoons.)

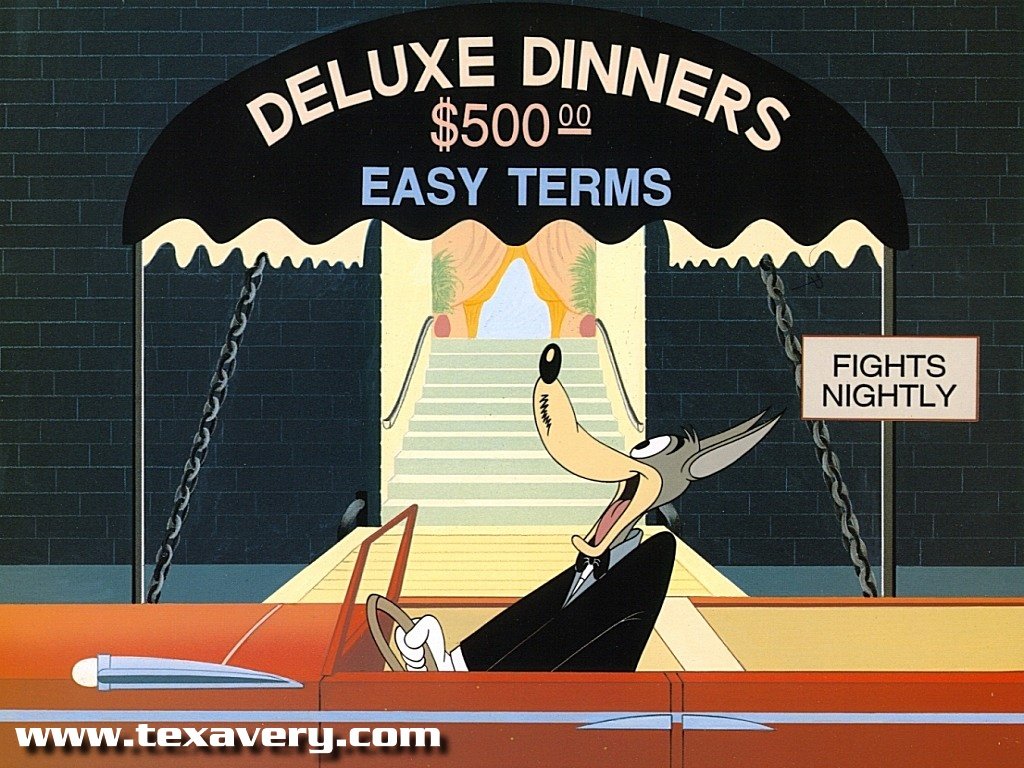

It’s too bad she didn’t publish this book online–in which case I presume she would have had as little difficulty in illustrating the graphic brilliance of Avery as I’m having here by scavenging diverse items from the Internet. For starters, here are three more characteristic samples:

One of the more interesting challenges in viewing Avery’s vintage MGM work is learning how to process various aspects of their racism and sexism without overlooking their good-humored humanity or drowning in political correctness. Read more