From the August 1, 1989 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

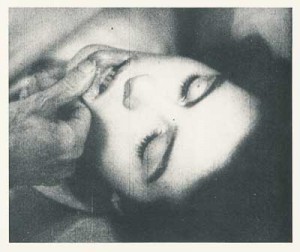

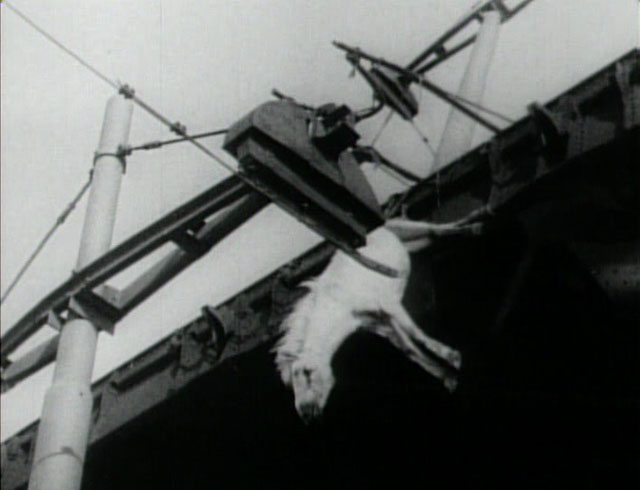

The greatness of Carl Dreyer’s first sound film (1932, 83 min.) derives partly from its handling of the vampire theme in terms of sexuality and eroticism and partly from its highly distinctive, dreamy look, but it also has something to do with Dreyer’s radical recasting of narrative form. Synopsizing the film not only betrays but misrepresents it: while never less than mesmerizing, it confounds conventions for establishing point of view and continuity, inventing a narrative language all its own. Some of the moods and images conveyed by this language are truly uncanny: the long voyage of a coffin, from the apparent viewpoint of the corpse inside; a dance of ghostly shadows inside a barn; a female vampire’s expression of carnal desire for her fragile sister; an evil doctor’s mysterious death by suffocation in a flour mill; a protracted dream sequence that manages to dovetail eerily into the narrative proper. The remarkable sound track, created entirely in a studio (in contrast to the images, which were all filmed on location), is an essential part of the film’s voluptuous and haunting otherworldliness. (Vampyr was originally released by Dreyer in four separate versions — French, English, German, and Danish; most circulating prints now contain portions of two or three of these versions, although the dialogue is pretty sparse.) Read more