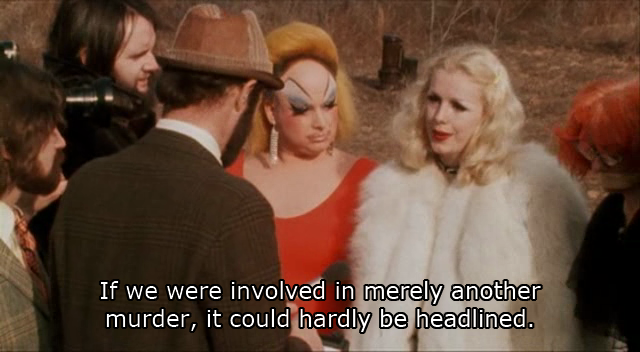

From the Chicago Reader (May 1, 1991). — J.R.

Jean-Luc Godard’s third feature and first studio production (1960) starts with a subversive premise: a neorealist musical in which the major characters (Jean-Paul Belmondo, Anna Karina, and Jean-Claude Brialy) can’t really sing and dance, much as they’d like to. Periodically ravishing to look at (it’s Godard’s first foray into both color and ‘Scope) and listen to (Michel Legrand did the nonsinging score), it’s also highly deconstructive in the way it keeps jostling us away from these pleasures and in the general direction of indecorous reality. (It’s also packed with both subtle and obvious references to other movies.) While its slender plot (stripper Karina wants a baby and turns to Belmondo when her boyfriend Brialy won’t oblige her) can irritate in spots, the film’s high spirits may still win you over. It’s perhaps most memorable for being a highly personal documentary about Karina and Godard’s feelings about her at the time, brimming with odd details and irreverent energies. In French with subtitles. 83 min. (JR)

Read more