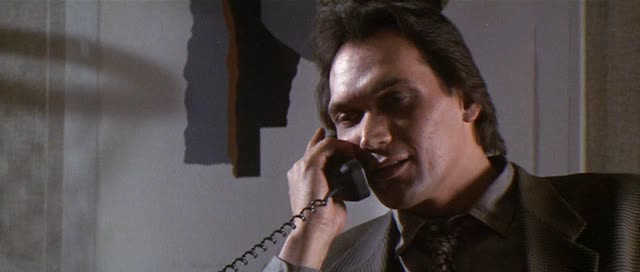

From the July 1, 1994 Chicago Reader.

Robert Zemeckis, combining his taste for brittle comedy (Used Cars), mutilated bodies (Death Becomes Her), and recycled history (Back to the Future and Who Framed Roger Rabbit), won an Oscar for this tear-jerking 1994 comedy about a slow-witted southerner (Tom Hanks) living through an absurdist half century of American great events. Zemeckis banks on the innocence of two parties, Gump and the spectator, homogenizing culture and politics into a safe, sweet, palatable nugget. Judging by the the movie’s enduring popularity, the message that stupidity is redemption is clearly what a lot of Americans want to hear. With Robin Wright, Gary Sinise, Mykelti Williamson, and Sally Field; Eric Roth and Zemeckis adapted a novel by Winston Groom. PG-13, 142 min. (JR) Read more