From the Chicago Reader (July 3, 1998). — J.R.

Out of Sight

Rating * Has redeeming facet

Directed by Steven Soderbergh

Written by Scott Frank

With George Clooney, Jennifer Lopez, Ving Rhames, Don Cheadle, Dennis Farina, Albert Brooks, Steve Zahn, and Catherine Keener.

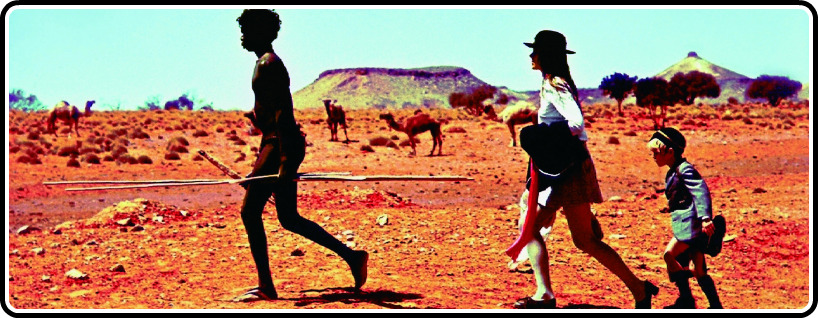

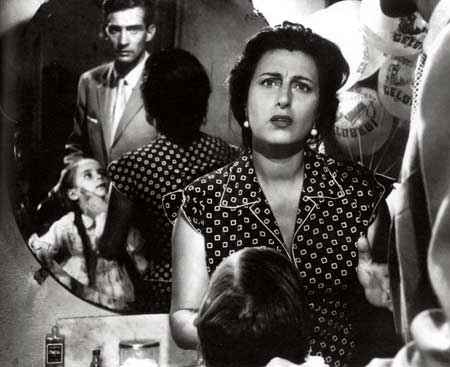

The Brigands: Chapter VII

Rating *** A must see

Directed and written by Otar Iosseliani

With Amiran Amiranachvili, Alexi Djakeli, Dato Gogibedachvili, Guio Tzintsadze, Nino Ordjonikidze, Keti Kapanadze, and Nino Kartsivadze.

Which would you rather see? A Hollywood thriller with hot stars whose director is so alienated from his material that he’s reduced to a kind of ingenious doodling while his characters disintegrate? Or a witty, despairing French-Russian-Italian-Swiss art movie set in 16th-century Georgia, Stalinist Georgia, contemporary Georgia, and contemporary Paris, whose writer-director is so much in command of his materials that he can plant the same actors in all four settings yet provide a seamless continuity?

My question is mainly rhetorical because it’s already been decided for most people reading this. Out of Sight, a major Universal release written by Scott Frank and directed by Steven Soderbergh, is playing all over town and will be around for weeks; The Brigands: Chapter VII, written and directed by Otar Iosseliani, doesn’t even have a U.S.