From the Chicago Reader (May 19, 1989). — J.R.

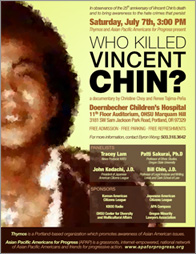

WHO KILLED VINCENT CHIN?

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Christine Choy.

Item: The December 22, 1941, issue of Life magazine features a two-page spread headlined “How to Tell Japs From the Chinese: Angry Citizens Victimize Allies With Emotional Outburst at Enemy.” It begins: “In the first discharge of emotions touched off by the Japanese assaults on their nation, U.S. citizens have been demonstrating a distressing ignorance on the delicate question of how to tell a Chinese from a Jap. Innocent victims in cities all over the country are many of the 75,000 U.S. Chinese whose homeland is our stanch ally. So serious were the consequences threatened, that the Chinese consulates last week prepared to tag their nationals with identification buttons. To dispel some of this confusion, Life here adduces a rule-of-thumb from the anthropometric conformations that distinguish friendly Chinese from enemy alien Japs.” Around this text and the two paragraphs that follow are four large photographs with inscriptions that attempt to spell out distinguishing characteristics of Chinese and Japanese physiognomies and body types.

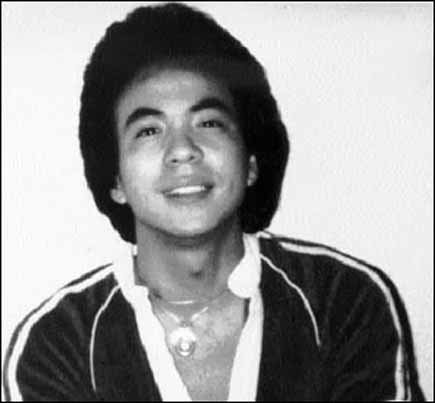

Item: In 1982 in Highland Park, Michigan, Vincent Chin, a 27-year-old Chinese auto engineer, got into a fight with Ronald Ebens, a somewhat older Caucasian autoworker, in a topless bar called the Fancy Pants. According to witnesses, the fight was precipitated by Ebens’s remark: “It’s because of you little motherfuckers that we’re out of work” — which implied that he thought Chin was Japanese and therefore somehow responsible for the massive layoffs in Detroit brought about by the influx of Japanese cars. (At the time of the incident, there was about 17 percent unemployment in Detroit, and local media showed some irate locals smashing Japanese cars with sledgehammers.) Outside the Fancy Pants, Ebens took a baseball bat out of his car and, accompanied by his stepson Michael Nitz (who was also involved in the barroom brawl), chased after Chin and beat him repeatedly; Chin, who was to have been married within the week, was taken to the hospital, where he died four days later.

This incident forms the core of Who Killed Vincent Chin?, a documentary cosigned by director Christine Choy and producer and interviewer Renee Tajima that was recently nominated for an Academy Award. But the complex aftermath of the murder is equally important to the film’s focus. Originally brought to trial for second-degree murder, Ebens and Nitz managed to get their charges reduced to manslaughter (which eliminated the necessity of a jury trial), and were then let off with three years’ probation and a $3,000 fine. After much heated protest in the Asian-American community, the case was appealed in federal court as a civil rights case, where a jury of seven women and five men acquitted Nitz but found Ebens guilty; he was sentenced to 25 years in prison. Then a federal appeals court ordered a new trial because of “trial errors,” and at a second trial held in Cincinnati, nine men and three women found Ebens not guilty on both counts.

In many respects, it’s a fascinating and disturbing case, and Choy and Tajima’s film certainly gives a great deal of attention to what is fascinating and disturbing about it. What it doesn’t do, however, is leave us with an account of the whole affair that is satisfying rather than merely suggestive. While the film leaves no doubt that Vincent Chin was brutally murdered for at least partially racial reasons, and that his killer got off virtually scot-free, it throws up countless questions about the legal proceedings and then leaves them hanging.

This lack of clarity and resolution partly stems from the film’s formal structure, which is also paradoxically part of its strength. Beginning like a TV teaser, the film rapidly cuts from interviews to clips of various TV news shows (including subtitled Japanese coverage of the events) and back again, creating a fragmented, almost scattershot mosaic construction that only gradually makes the basic facts of the case clear to us.

Deliberately designed to resemble the disorienting mix produced by switching TV channels, the film certainly casts its net wide — Ebens himself is accorded at least as much interview footage as Vincent Chin’s mother, Lily, and Helen Zia, who often serves as spokesperson for the Asian-American protests — but the fish caught in this net are generally wriggling so fast that we can’t concentrate on them for any extended length of time.

The advantage of this approach is that it brings to the fore the bewilderingly incomplete methods of most TV news reports — becoming, in effect, a comment on media coverage as well as an account of the murder case. (Unlike the old Hollywood cliche showing various overlapping newspapers with blaring headlines reporting the same event, this cacophony offers no hint of consensus.) The disadvantage of the approach is that it leaves so many unanswered questions — such as what the “errors” were in the first federal trial, and precisely what the two charges were in the second — that it’s not possible to follow the chronology of events as closely as we’d like to.

Some (if not all) of this confusion may simply be a reflection of what’s emphasized and ignored in the trials themselves. About two years ago, I attended a trial in Santa Barbara involving what appeared to me to be a racial incident: a black youth got into a scuffle with some rowdy white college jocks in a McDonald’s, and immediately afterward took a machete out of his car and slashed one of the boys in the arm. According to the black youth, who was being defended by a court appointee (and who was subsequently given a fairly stiff sentence), the fight was provoked by a racist epithet, which all the white boys present denied was ever spoken (as vehemently, I should add, as Ebens and his family, friends, and defense attorney deny that Ebens ever made a racial remark).

In determining the truth or falsity of this claim, a great deal of attention was paid to the mood and behavior of the college kids that night, but the choices made about what to concentrate on — by both the prosecution and the defense (who claimed that the incident was a racial one) — were astonishing. Before heading for the McDonald’s, the college kids had all watched a movie together on video; while it was of enormous interest in the courtroom what each of these boys ordered to eat — how many hamburgers or cheeseburgers, whether they ordered french fries or milkshakes or sodas (and if so, what kind of milkshakes or sodas) — no one present had the slightest interest in what movie the boys had just seen.

We’re not shown any of the three trials that took place in the Vincent Chin case, although it’s strongly implied by one commentator that the not guilty verdict in Cincinnati was largely determined by the conservative cast of that city and its remoteness from the racial conflicts in Detroit five years earlier. What the film does manage to establish, however, which replicates the overall impression I had in that Santa Barbara courtroom, is that a detailed sense of what actually happened at the Fancy Pants that night is irretrievable — not because memories are too vague and unreliable, but because too many preexisting assumptions get in the way of objective recollection. To put it as bluntly as possible, no one really wants to know exactly what happened, because the significations are too highly charged to make an objective description of events desirable.

Comparable questions were recently raised by the much slicker and artier Errol Morris film The Thin Blue Line, which exposed another case of legal injustice. If the Morris film managed to garner some extra press — through both its failure to get an Oscar nomination and its eventual (and more important) success in freeing a man wrongly convicted of a murder — it raised similar (and similarly ignored) questions about the importance given to general issues over the clarification of facts in the case.

On the other hand, it might be argued that Choy and Tajima are not interested in giving us the comforting sense of closure and (false) knowledge that comes with the average news story, or even with conventional agitprop. While the forces represented in the film tend to be polarized around separate interpretations of what happened, the film is explicitly not trying to segregate the truth along racial lines, and neither the implied audience of this film nor its major spokespeople are defined strictly according to race. (Although the filmmakers are of Chinese and Japanese descent — filmmaker and cinematographer Choy was born in Shanghai, and Chicagoan Tajima is currently a film critic for the Village Voice — the film does not ask to be read as an “Asian” statement.) As we simultaneously witness a denial of racial motives behind the crime and an exposure of racial attitudes on every level, we gradually come to realize that the film’s title is less literal than it may first appear — that the who of the title (as well as the implied what) leads to questions that eventually take in the society as a whole, and therefore address the entirety of the film’s possible audience.

The murky twists and byways of Ebens’s comments about American Citizens for Justice (the organization that eventually brought the case to the federal courts) and then about Asian Americans in general give one vivid insight into the process of confused thinking about race, even if the content of what he’s saying is so elusive that it winds up as near-gibberish: “I personally think that a lot of them used it for their own vehicle just to get ahead. Secondly, they used it to, you know, promote the Asia-America [sic] and their alleged plight in this country — which I am not aware of, that they have a plight, because I know very few Asians — very few — and the ones that I do know have always been really nice people. In fact, my daughter helped, or used to help, an Asian kid at school.”

While Who Killed Vincent Chin? is concerned with the profound separations between the Caucasian and Asian communities of Detroit, these separations are contested as well as dramatized by the dialectical editing style, which tends to give us contrasting interpretations of the same data back to back. (Particular mileage is gotten out of juxtaposing Ebens and Chin’s mother responding separately to the same issues.) In this respect, a movie about alienation manages to resist alienation itself — forging links between elements that conventional media contrive to keep apart.