From the Chicago Reader (October 22, 1993). — J.R.

SHORT CUTS

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Robert Altman

Written by Altman and Frank Barhydt

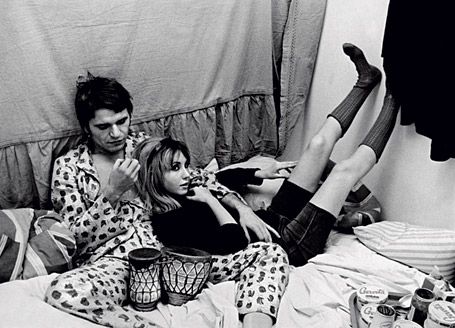

With Anne Archer, Bruce Davison, Robert Downey Jr., Peter Gallagher, Jennifer Jason Leigh, Jack Lemmon, Lyle Lovett, Andie MacDowell, Frances McDormand, Matthew Modine, Julianne Moore, Chris Penn, Tim Robbins, Annie Ross, Lori Singer, Madeleine Stowe, Lili Taylor, Lily Tomlin, Fred Ward, and Tom Waits.

Annie Ross — the tough and resourceful British-born jazz singer Kenneth Tynan once called “a carrot-head who moves us and then brushes off our sympathy with a shrug of her lips” — projects the kind of caustic soul that seems made for a Robert Altman film. And nothing in Altman’s 189-minute Short Cuts moves me quite as much as her rendition of “I’m Gonna Go Fishin’,” sung and swung over the final credits, which roll past a set of overlapping maps of Los Angeles.

The number meshes with the movie in unexpected and mysterious ways. Its trout-fishing motif sends us back to one of the film’s key episodes and its aftermath — a trout dinner for two couples on a terrace overlooking LA that expands into an all-night party, a recapitulation of many of this movie’s other motifs and themes: Jeopardy, clown costumes, makeup, marital infidelity, partying, unemployment. Read more