From the Chicago Reader (December 1, 2000). — J.R.

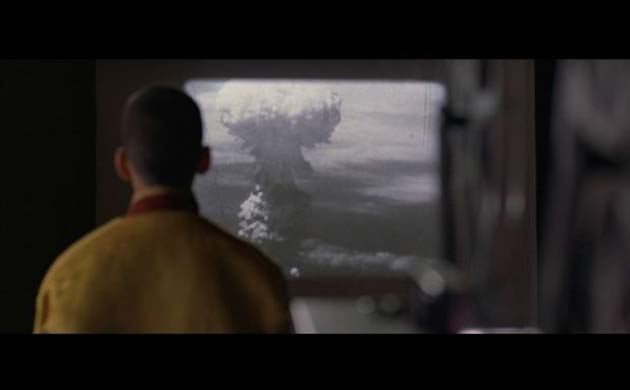

Requiem for a Dream

**

Directed by Darren Aronofsky

Written by Hubert Selby Jr. and Aronofsky

With Ellen Burstyn, Jared Leto, Jennifer Connelly, Marlon Wayans, Christopher McDonald, and Louise Lasser.

Darren Aronofsky’s first feature, Pi (1998), had more style than substance — or perhaps it’s just that the only thing I now remember with much clarity is its razzle-dazzle style. The black-and-white cinematography and the jazzy editing were pretty attractive in a disposable sort of way, though critic Bill Boisvert had a point when he suggested in these pages that the attitude of this metaphysical thriller was “profoundly anti-intellectual,” rightly adding that this was “true of most indie genius films.” (He may have been more right than he realized. His second example was the 1997 Good Will Hunting, directed by Gus Van Sant, who’s been offering us nothing but anti-intellectual holiday releases about geniuses ever since — with Alfred Hitchcock rather than Norman Bates as the prodigy in the 1998 Psycho remake and Robert Brown taking the equivalent role in Finding Forrester, which opens on Christmas day.)

When I belatedly caught up with Aronofsky’s second feature, Requiem for a Dream, it was with the hope of seeing something more than just fancy style. Read more