From the Chicago Reader (November 15, 2007). — J.R.

Still Lives: The Films of Pedro Costa Gene Siskel Film Center, 11/17—12/4

The cinema of Portuguese filmmaker Pedro Costa is populated not so much by characters in the literary sense as by raw essences — souls, if you will. This is a trait he shares with other masters of portraiture, including Robert Bresson, Charlie Chaplin, Jacques Demy, Alexander Dovzhenko, Carl Dreyer, Kenji Mizoguchi, Yasujiro Ozu, and Jacques Tourneur. It’s not a religious predilection but rather a humanist, spiritual, and aesthetic tendency. What carries these mysterious souls, and us along with them, isn’t stories — though untold or partially told stories pervade all six of Costa’s features. It’s fully realized moments, secular epiphanies.

Born in Lisbon in 1959, by his own account Costa grew up without much of a family, and famly life — actual or simulated — is central to his work. All his films are about the dispossessed in one way or another. As the Argentine film critic Quintín puts it, he’s “a cool guy — very rock ’n’ roll” (in fact he was a rock guitarist before he turned to filmmaking). “At the same time,” Quintín continues, he is “quietly telling whoever will listen that cinema is exactly the opposite of what 99% of the film world thinks, and he is getting more radical every day.”

One can’t claim Costa is critically unrecognized. His films have been discussed very perceptively by Thom Andersen, Tag Gallagher, Shigehiko Hasumi, James Quandt, Mark Peranson, and Jeff Wall, among others. (Look online for fine essays by Costa and Hasumi in Rouge and by Gallagher in Senses of Cinema.) But, like Kira Muratova and Pere Portabella, he’s never had a feature in the Chicago or New York film festivals, and he’s been ignored or scorned by most of the mainstream critics at Cannes. Now the Gene Siskel Film Center is offering a retrospective of all his features (though lamentably none of his shorts).

Despite his rigor and his attachment to avant-garde filmmakers Jean-Marie Straub and Daniele Huillet — the subjects of his fifth and most accessible feature, Where Lies Your Hidden Smile? (2001) — many of Costa’s cinematic reference points are Hollywood auteurs. You could even say that he’s been consciously remaking some of the movies of John Ford, Howard Hawks, Fritz Lang, and Tourneur on his own terms — in Portuguese slums, most recently in digital video, with nonprofessional actors, some of them exiles from the former Portuguese colony of Cape Verde or junkies. Though this makes the films sound crude, the dialogue is scripted, the scenes are rehearsed and shot several times, and visual beauty is a constant. Colossal Youth (2006) can be seen as a remake of Ford’s theatrically lit Sergeant Rutledge (1960, see upper photo above), with the traumatized Cape Verdean patriarch Ventura standing in for Woody Strode. And Costa’s frequently dazzling color palettes derive in part, he says, from having watched Ford’s She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (1949, see lower photo above) “very, very stoned.”

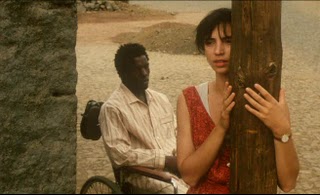

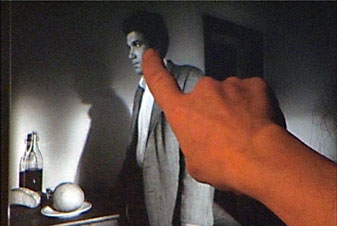

Costa’s films have the reputation of being difficult, but I would argue that three of them are relatively accessible. I had no trouble diving headfirst into his first color feature, Casa de Lava (1994, stupidly translated as Down to Earth), a voluptuous remake of Tourneur’s 1943 film I Walked With a Zombie; the zombie here is Isaach de Bankolé, playing a construction worker in a protracted coma. And Costa’s black-and-white first feature, The Blood(1989), was gripping even though I couldn’t follow all of the plot, its fairy-tale poetics evoking Charles Laughton’s The Night of the Hunter (1955) and its milky whites, inky blacks, and delicate balances of light and shadow suggesting Lang’s The Big Heat (1953) and Bresson’s Pickpocket (1959). Where Lies Your Hidden Smile? shows Straub and Huillet editing their 1999 feature Sicilia!, making only five cuts per day and quarreling endlessly over each one; it reveals the difference a single frame can make and how much the two need each other. Aptly described as a romantic comedy, it’s the only Costa feature that isn’t sad and the best film ever made about filmmaking.

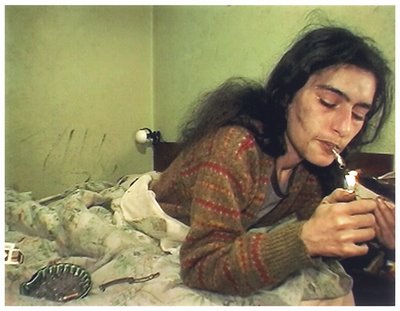

But teasing out the narrative in the other three features — all shot in Lisbon slums and hovels, many being audibly and visibly razed — is no easy matter. And getting used to their idiosyncrasies is a challenge because, as Quintín suggests, you have to accept Costa’s terms, which means rethinking the way you watch movies. Bones (1997), In Vanda’s Room (2000), and Colossal Youth focus on some of the same people and places. Bones was shot on film with a conventional crew and has a conventional running time (94 minutes); the actors, though mostly nonprofessionals, play characters with different names. But Costa himself shot the latter two on DV over several years, using crews of just two or three people. They’re both about three hours long, the camera never moves, and the performers, all nonprofessionals, play themselves.

The most common complaint about Costa is that he aestheticizes poverty. But the same complaint could be made against many novelists — Nelson Algren, for instance — and countless visual artists. None of Costa’s aestheticizing makes abject poverty look attractive, and much of it confounds the very notion that neorealism opens a door onto the world. Costa himself describes what he creates as “a closed door that leaves us guessing” — the title of a lecture he gave in Tokyo, presented on the Rouge site. Given how obsessed he is with doors and windows in his films, it’s a literal as well as figurative description of his work. “Fiction is always a door that we want to open or not — it’s not a script,” he said. “We’ve got to learn that a door is for coming and going. I believe that today, in the cinema, when we open a door, it’s always quite false, because it says to the spectator: ‘Enter this film and you’re going to be fine, you’re going to have a good time,’ and finally what you see in this genre of film is nothing other than yourself, a projection of yourself.”

There’s no way you can project yourself into Casa de Lava, Bones, In Vanda’s Room (Costa’s toughest film), or Colossal Youth. Costa even discourages identification by refusing to shoot reverse angles, Hollywood’s conventional way of drawing us into the characters’ space. But it’s hard to be indifferent toward these characters and what they do (or don’t do). Costa combines Straub and Huillet’s fanatical belief in capturing material reality with a more disembodied search for spiritual essence found in some chamber works by Tourneur and Dreyer. What emerges from this apparent contradiction is a passageway designed for coming and going, not a simple portal that opens onto “the truth.” Rather than charge onto the premises, we go back and forth to get our bearings, and Costa’s beautifully constructed sounds and images are our guide and not a destination. For all their difficulty, and despite the fact they build on older work, Costa’s films are the cinema of the future, partly because of their intimate scale. As we get to know them better, they steadily grow in stature.

Costa’s films have the reputation of being difficult, but I would argue that three of them are relatively accessible. I had no trouble diving headfirst into his first color feature, Casa de Lava (1994, stupidly translated as Down to Earth), a voluptuous remake of Tourneur’s 1943 film I Walked With a Zombie; the zombie here is Isaach de Bankolé, playing a construction worker in a protracted coma. And Costa’s black-and-white first feature, The Blood (1989), was gripping even though I couldn’t follow all of the plot, its fairy-tale poetics evoking Charles Laughton’s The Night of the Hunter (1955) and its milky whites, inky blacks, and delicate balances of light and shadow suggesting Lang’s The Big Heat (1953) and Bresson’s Pickpocket (1959). Where Lies Your Hidden Smile? shows Straub and Huillet editing their 1999 feature Sicilia!, making only five cuts per day and quarreling endlessly over each one; it reveals the difference a single frame can make and how much the two need each other. Aptly described as a romantic comedy, it’s the only Costa feature that isn’t sad and the best film ever made about filmmaking.

But teasing out the narrative in the other three features — all shot in Lisbon slums and hovels, many being audibly and visibly razed — is no easy matter. And getting used to their idiosyncrasies is a challenge because, as Quintín suggests, you have to accept Costa’s terms, which means rethinking the way you watch movies. Bones (1997), In Vanda’s Room (2000, see three photos above), and Colossal Youth focus on some of the same people and places. Bones was shot on film with a conventional crew and has a conventional running time (94 minutes); the actors, though mostly nonprofessionals, play characters with different names. But Costa himself shot the latter two on DV over several years, using crews of just two or three people. They’re both about three hours long, the camera never moves, and the performers, all nonprofessionals, play themselves.

The most common complaint about Costa is that he aestheticizes poverty. But the same complaint could be made against many novelists — Nelson Algren, for instance — and countless visual artists. None of Costa’s aestheticizing makes abject poverty look attractive, and much of it confounds the very notion that neorealism opens a door onto the world. Costa himself describes what he creates as “a closed door that leaves us guessing” — the title of a lecture he gave in Tokyo, presented on the Rouge site. Given how obsessed he is with doors and windows in his films, it’s a literal as well as figurative description of his work. “Fiction is always a door that we want to open or not — it’s not a script,” he said. “We’ve got to learn that a door is for coming and going. I believe that today, in the cinema, when we open a door, it’s always quite false, because it says to the spectator: ‘Enter this film and you’re going to be fine, you’re going to have a good time,’ and finally what you see in this genre of film is nothing other than yourself, a projection of yourself.”

There’s no way you can project yourself into Casa de Lava, Bones, In Vanda’s Room (Costa’s toughest film), or Colossal Youth. Costa even discourages identification by refusing to shoot reverse angles, Hollywood’s conventional way of drawing us into the characters’ space. But it’s hard to be indifferent toward these characters and what they do (or don’t do). Costa combines Straub and Huillet’s fanatical belief in capturing material reality with a more disembodied search for spiritual essence found in some chamber works by Tourneur and Dreyer. What emerges from this apparent contradiction is a passageway designed for coming and going, not a simple portal that opens onto “the truth.” Rather than charge onto the premises, we go back and forth to get our bearings, and Costa’s beautifully constructed sounds and images are our guide and not a destination. For all their difficulty, and despite the fact they build on older work, Costa’s films are the cinema of the future, partly because of their intimate scale. As we get to know them better, they steadily grow in stature.