This was written for a brochure to accompany a retrospective held by Northwestern University’s Block Cinema in January 2008. — J.R.

ZHANGKE JIA, POETIC PROPHET

by Jonathan Rosenbaum

What is it about Zhangke Jia that makes him the most exciting

mainland Chinese filmmaker currently working? It might be

oversimplifying matters to describe this writer-director, born in

1970, as a country boy. But the fact that he hails from the small town

of Fenyang in northern China’s Shanxi province clearly plays an

important role in all his features to date. (I’m less certain about what

role it plays in his two recent documentaries, Dong [2006] and

Useless [2007].) Like William Faulkner and Alexander Dovzhenko,

Jia is a hick avant-gardist in the very best sense — someone whose

outsider/minority status enhances both his humanity and his art.

Working in long, choreographed takes, and mixing realistic accounts

of working-class life with diverse forms of cultural shock and fantasy

ranging from animation to SF to rock, he already qualifies as a poetic

prophet of the 21st century, and not only for China.

He attended the Beijing Film Academy, where he

completed his first film, the one-hour Xiao Shan

(Going Home, 1995). I haven’t seen it, but according

to critic Kevin Lee, it’s about a country boy and

unemployed cook in Beijing who wants to go home for

the Chinese New Year and runs into numerous obstacles,

and it utilizes literary intertitles (which also crop up in

his last two features). Jia’s identification with his rural

hero is apparently underlined in a party sequence where

he appears, speaking drunkenly in his semi-incoherent

Shanxi dialect. (He can be found doing something similar

in the opening sequence of Uncommon Pleasures.)

Given that nearly all Chinese films are dubbed into Mandarin,

this could be seen as a defiant move, comparable to the

direct-sound recording of Taiwanese dialects in the work of

Hou Hsiao-hsien, one of Jia’s key influences.

Fenyang is the main setting in Kiao Wu (Pickpocket,

1997) — another eccentric character study named after its

leading character —- and his second and most ambitious

feature, Platform (2000), an epic following the teenage

members of Fenyang’s state-run Peasant Culture Group

as they gradually mutate over a decade into the privatized

All-Star Rock and Breakdance Electronic Band. In fact,

Platform was scripted before Xiao Wu but made

afterwards because it was far more expensive to finance;

like Jia’s subsequent Unknown Pleasures (2002), it

was an underground independent film — technically banned,

though it circulated in China on pirated video.

Both Unknown Pleasures and In Public (2002) — a half-hour

documentary shot on digital video that scouted locations for the

feature — were shot in another small town in Shanxi about to be

transformed by capitalism, Datung. And even though Jia returned

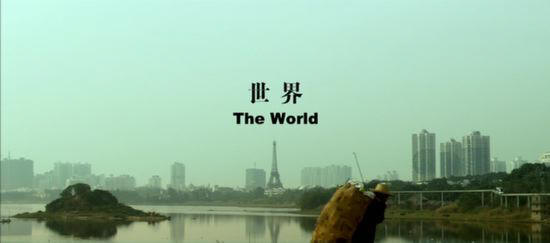

to Beijing to shoot The World (2004), about alienated workers in

a theme park, and went on to the equally spectacular Three Gorges

Dam in central China for Still Life (2006), leading characters in

both films hail from Shanxi province. So his roots remain, but he

continues to grow. And now that he’s officially recognized by the

Chinese government, he shoots all his features on digital video.