From the Chicago Reader (November 13, 1987). — J.R.

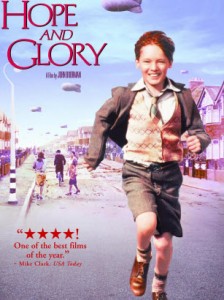

HOPE AND GLORY

*** (A must-see)

Directed and written by John Boorman

With Sebastian Rice Edwards, Sarah Miles, David Hayman, Derrick O’Connor, Susan Wooldridge, Sammi Davis, and Ian Bannen.

Disasters sometimes take on a certain nostalgic coziness when seen through the filter of public memory. Southerners’ recollections of the Civil War and the afterglow felt by many who lived through the Depression are probably the two strongest examples of this in our national history — perhaps because such catastrophes tend to bring people together out of fear and necessity, obliterating many of the artificial barriers that keep them apart in calmer times. When I attended an interracial, coed camp for teenagers in Tennessee in the summer of 1961, shortly after the Freedom Rides, the very fact that our lives were in potential danger every time we left the grounds en masse — or were threatened with raids by local irate whites — automatically turned all of us into an extended family. Considering some of the cultural differences between us, I wonder if we could have bridged the gaps so speedily if the fear of mutually shared violence hadn’t been so palpable.

The images that we inherit of other people’s disasters are often suffused by a similar nostalgia. Richard Attenborough’s Cry Freedom exploits this fact rather shamelessly, seeking to give audiences a feeling of emotional solidarity against apartheid that seems designed to last only until the house lights come on. In Hey Babu Riba — a sort of Yugoslav version of The Last Picture Show set in the 50s that is currently at Facets Multimedia — a group of high school friends and their families are all warmly united by their shared contempt for the Soviet stooges in their midst. The only strongly felt sequence in the mainly unfelt Radio Days shows a family drawing together over the tragedy of a little girl trapped in a well. And long before I saw Hope and Glory, John Boorman’s sprightly and multifaceted autobiographical account of the sublime pleasures he enjoyed as a seven-year-old during the London blitz, I was already primed by Graham Greene and the opening sections of Gravity’s Rainbow to view that event as sexy and romantic.

So Boorman’s “revisionist” view of life in the London suburbs in the early 40s and the attitude this reflects aren’t something new in the public imagination. But they are something new and unexpected to find in a John Boorman film. When the hero’s older sister Dawn (Sammi Davis) runs outside during an air raid and delightedly exclaims, “Look, come and see the fireworks!” or when her mother Grace (Sarah Miles) agrees to her having premarital sex with a Canadian soldier (“What does it matter? We may all be dead tomorrow”), we may feel like we’ve been there before; but it certainly wasn’t Boorman who took us there.

Part of the fascination of Hope and Glory rests in the degree to which it redefines the nine Boorman features that preceded it. Along with fascination, it is possible to feel a certain ambivalence: as much as I enjoy, respect, and admire the movie on its own terms, the recasting of the Boorman oeuvre that it implies makes me a little uneasy. To oversimplify a bit, the seven-year-old boy’s view of the cosmos that informs much of what is most exciting about Point Blank, Leo the Last, Zardoz, Exorcist II: The Heretic, Excalibur, and The Emerald Forest looks a lot different when it’s contained in and by a seven-year-old character, living in a world that we more readily recognize as our own.

The conventional wisdom about this would be that Boorman, now in his mid-50s, has finally grown up. The question that nags at me is whether, in the process, he might have grown down in some ways as well. After all, Boorman may be the first large-scale adolescent romantic to have emerged in the English cinema since Michael Powell, the director (or codirector) of The Thief of Bagdad, The Red Shoes, and Peeping Tom. (I’m deliberately excluding Ken Russell from the competition, a postromantic decadent if there ever was one.) And who in their right minds would ever want Michael Powell to grow up, even in his 80s?

If memory serves, all of the earlier Boorman features mentioned above, with the exceptions of The Heretic and Excalibur, were shot in a ‘Scope format. Hope and Glory isn’t, and given the intimacy and scale of its subject matter, it shouldn’t have been. While the multiple set constructed for the film covered over 50 acres — making it, according to Boorman, “probably the largest set built in Britain since the war” — the suburban neighborhood of semidetached houses that forms its centerpiece feels much too snug to register on an epic scale. Even in the most spectacular scene, when a barrage balloon breaks free of its moorings and knocks against buildings, the magic of the moment feels circumscribed, as if it were all occurring under a circus tent. (Like the bite-size cosmology of Italo Calvino’s Cosmicomics or the town’s expedition to look at an ocean liner in Fellini’s Amarcord, it feels pared down to a child’s perspective.)

While most treatments of war from Homer to Tolstoy and from All Quiet on the Western Front to Full Metal Jacket balance intimate details with an epic scale, these are all treatments that include soldiers as well as civilians. In Hope and Glory, barring only a pathetic-looking grounded German pilot, the aforementioned Canadian boyfriend, and the hero’s noncombatant father, Clive (David Hayman), there are no real warriors at all — none, that is, except for the seven-year-old boy and his classmates, the only consistently violent characters that we see. And however much the film’s episodes are viewed from a child’s perspective, the narrating voice of Boorman, situated in the present, situates them within a broader context.

For a director as personal and as self-conscious as Boorman, Hope and Glory offers a golden opportunity to provide glosses and indirect commentaries on his earlier films, and he takes full advantage of it. Early in the movie, after seven-year-old Bill (Sebastian Rice Edwards) has established that Hopalong Cassidy is more real to him than the war raging outside, he is playing with toy lead figures. Narrating for him offscreen, Boorman identifies two of these figures as King Arthur and Merlin, and adds that “I was riding high through the enchanted forest”; in one fell swoop, his last two features, Excalibur and The Emerald Forest, are pinned neatly into place. The ambivalence of Boorman and Bill about growing up in a family dominated by women throws some light on the antiutopia run by women in the SF future society of Zardoz. Similarly, the weakness of Bill’s father — thrown into relief by Grace’s love for and devotion to Clive’s best friend, Mac (Derrick O’Connor) — links up with the mysterious patriarchal figures presiding over the metaphysical worlds of Point Blank and Zardoz. Both films chart the progress of their aboriginelike heroes as they claw their way to the top in order to confront these fearful rulers, only to discover at the end that these figureheads are ineffectual clowns — Carroll O’Connor and the Wizard of Oz, respectively.

The effect of this psychoanalytical reading of Boorman’s obsessions is, in one sense, to belittle them. But the beginning of his career as a feature director coincided with the advent of pop art in the mid-60s, and Boorman’s grasp of that movement’s iconography tended to distance and leaven with cool irony his more overheated mythological concerns. The latter usually juxtaposed a Rousseau-like version of Natural Man and the faceless abstractions of modern technology, and there was often a sense of comedy as well as tragedy in the resulting collisions: Lee Marvin training his gun on an empty mattress or a telephone (Point Blank), Sean Connery teaching himself to read L. Frank Baum (Zardoz). Tarzan Versus IBM, an alternative title proposed by Godard for Alphaville, would serve almost equally well for Point Blank, Zardoz, Deliverance, The Heretic, or The Emerald Forest. If critics tended to balk at these films’ intellectual pretensions while usually tolerating their equally puerile macho conceits — so that Zardoz was considered a hoot while the comparably inflated Deliverance was regarded as “serious” — Hope and Glory avoids such objections by proposing itself as a comic book for adults, and an understated English one at that.

But the earlier movies had at least the courage of their silliness, which gave them a wide-eyed conviction and vibrancy that Hope and Glory, for all its beauties, lacks. The latter holds its own as a film (in the art house sense), but as a movie it misses the wildness and reckless risk taking of earlier Boorman.

Some of this difference may be a matter of roots and national identities. If the Anglophobia of the auteurist revolution in film taste that occurred in the 60s tended to exempt Boorman, along with Alfred Hitchcock and Joseph Losey, this was largely because Boorman, like Hitchcock and Losey, wasn’t perceived as a purely English filmmaker. After a low-budget first feature with the Dave Clark Five in 1965 (Catch Us if You Can, released in the U.S. as Having a Wild Weekend), Boorman became an expatriate, settling first in Los Angeles and later in Ireland. Prior to Hope and Glory, his only pictures with English settings and subjects since his first were Leo the Last and Excalibur, neither of which could be regarded as “typically” English. Indeed, considering Boorman’s usual metaphysical bents, it seems fitting that the only critical book devoted to him to date is by a Frenchman, Michel Ciment.

From this standpoint, Hope and Glory is a homecoming film, and it is widely regarded as such in the English press. Although, ironically, only a fraction of the film is English-financed, English critics have been quick to praise the new Boorman for his very English lack of pretension. In the Monthly Film Bulletin, Charles Barr applauds the film’s refusal to tailor itself to an “international” (i.e., American) market by situating all its action prior to America’s main entry into the war, and by using cricket as a major motif. (Before going off to war as a typist, Clive teaches Bill how to perform a “googly” — succinctly described by Barr as “the wrist-spun off-break bowled, deceptively, with the action of a leg-break” — and Bill later uses this trick to defeat both his irascible grandfather and Clive himself, in separate matches.)

Portions of Hope and Glory are sentimental, but it must be admitted that Boorman generally doesn’t sentimentalize his younger self. When Grace is about to send Bill and his younger sister off to Australia for safety, he blurts out angrily, “I’m going to miss the war — and it’s all your fault!” Then, after she becomes hysterical and changes her mind, he chastises her for her emotional display and declares that he wants to leave after all. Mac has to step in to settle the issue.

One should add that some of the film’s more sentimental moments are also some of the best: Dawn singing “Begin the Beguine” while Grace accompanies her on piano; Grace’s handstand on a beach, and her inchoate expressions of longing for Mac in the same scene; the family’s arrival at the grandparents’ haven in Willow Mead — a site where the war seems magically absent — after their house accidentally goes up in flames; the triumphant exhilaration of the ending, complete with “Pomp and Circumstance” on the sound track. But at the same time that Boorman seduces us with such enchantments, he also deceives us with a crafty little googly of his own — persuading us that he is embarking on a fresh adventure while aiming straight for the heart of old-fashioned English cinema.