From the Chicago Reader (November 13, 1987). — J.R.

HOPE AND GLORY

*** (A must-see)

Directed and written by John Boorman

With Sebastian Rice Edwards, Sarah Miles, David Hayman, Derrick O’Connor, Susan Wooldridge, Sammi Davis, and Ian Bannen.

Disasters sometimes take on a certain nostalgic coziness when seen through the filter of public memory. Southerners’ recollections of the Civil War and the afterglow felt by many who lived through the Depression are probably the two strongest examples of this in our national history — perhaps because such catastrophes tend to bring people together out of fear and necessity, obliterating many of the artificial barriers that keep them apart in calmer times. When I attended an interracial, coed camp for teenagers in Tennessee in the summer of 1961, shortly after the Freedom Rides, the very fact that our lives were in potential danger every time we left the grounds en masse — or were threatened with raids by local irate whites — automatically turned all of us into an extended family. Considering some of the cultural differences between us, I wonder if we could have bridged the gaps so speedily if the fear of mutually shared violence hadn’t been so palpable.

The images that we inherit of other people’s disasters are often suffused by a similar nostalgia. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (March 1, 2002). — J.R.

Winner of the Golden Lion at the Venice film festival, this 1998 feature by Gianni Amelio (Stolen Children, Lamerica) wears its art, as well as its heart, on its sleeveso much so that I feel guilty for not liking it more. It explores the idealized love of an illiterate Sicilian worker (Enrico Lo Verso, who has the eyes of a rain-soaked basset hound) for his literate kid brother (Francesco Giuffrida) after they immigrate to Turin, but that love is supposed to spell out the meaning of his entire life, with other details (work, parents, wife and kids) made to seem strictly incidental. The same sense of hyperbole extends to Amelio’s arty and gloomy evocations of the period (1958-’64), though the literary way this is split up into six sections, each focusing on a single day and bearing its own one-word title, is rather elegant. In Italian with subtitles. 128 minutes. (JR) Read more

From the Chicago Reader (August 30, 2002). For the record, Fritz Lang’s line in Contempt about CinemaScope being appropriate only for snakes and funerals is a misattribution of a wisecrack that actually came from Orson Welles.– J.R.

Fritz Lang’s only film in CinemaScope (1955, 89 min.) is one of his most neglected features, at least in this country. (In France there’s a deluxe edition on DVD made especially for high school students.) A kind of 18th-century fairy tale about an orphan (Jon Whiteley) in Dorset who’s adopted, after a fashion, by a smuggler (Stewart Granger), this classy MGM production was adapted from a novel by J. Meade Faulkner by Margaret Fitts and Jan Lustig, and its dreamlike sense of wonder is equaled only in Lang’s German pictures. John Houseman produced, and Mikos Rozsa wrote the stirring score; the fine secondary cast includes George Sanders, Joan Greenwood, and Viveca Lindfors. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (July 1, 2002). — J.R.

I saw this French mystery thriller, the first feature of writer-director Gilles Mimouni, shortly after its 1996 release, and it left little residue. However, it has Romane Bohringer (Savage Nights), and that’s definitely a plus. Just before leaving Paris for Tokyo, the hero (Vincent Cassel), who’s engaged, thinks he spots an old flame (Monica Bellucci) in a cafe. He becomes obsessed with seeing her again, finds out where she lives, and hides out in her apartment — though he winds up having sex with Bohringer instead. In French with subtitles. 116 min. (JR) Read more

From the Chicago Reader (December 5, 2003). Criterion has released a Blu-Ray of this film. P.S. If you hit and load the second and third illustrations below, you can see them move slightly. — J.R.

I only recently caught up with Jaromil Jires’s overripe 1970 exercise in Prague School surrealism, now that it’s become available again, and I’m miffed that I had to wait so long. The 13-year-old title heroine, who’s just had her first period, traipses through a shifting landscape of sensuous, anticlerical, and vaguely medieval fantasy-horror enchantments that register more as a collection of dream adventures, spurred by guiltless and polysexual eroticism, than as a conventional narrative. Virtually every shot is a knockout — for comparable use of color, you’d have to turn to some of Vera Chytilova’s extravaganzas of the same period, such as Daisies and Fruit of Paradise. If you aren’t too anxious about decoding what all this means, you’re likely to be entranced. In Czech with subtitles; a 35-millimeter print will be shown. 77 min. Gene Siskel Film Center.

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (March 21, 2003). — J.R.

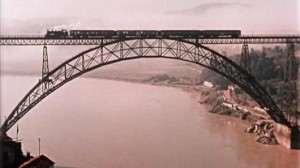

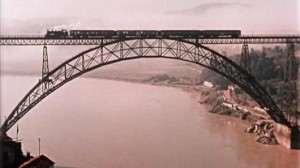

Manoel de Oliveira’s 2001 masterpiece explores the Portuguese city where he’s lived for more than 90 years, though it concentrates on the first 30 or so, suggesting that his childhood must have lasted a very long time. It’s a remarkable film for its effortless freedom and grace in passing between past and present, fiction and nonfiction, staged performance and archival footage (including clips from two of his earliest films, Hard Work on the River Douro and Aniki-Bobo) while integrating and sometimes even synthesizing these modes. He’s mainly interested in key images, music, and locations from the Eden of his privileged youth, and some of the film’s songs are performed by him or his wife — though we also get a fully orchestrated version of Emmanuel Nunes’s Nachtmusik 1. In Portuguese with subtitles. 61 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

I can’t remember the first time I met Gil Perez, but the first time I got in touch with him, which must have been in the late 60s, it was to reprint a remarkable essay of his about Murnau that had appeared in Sight and Sound for an anthology I was editing called Film Masters, a book that for various complex reasons never came out (although, if memory serves, it twice reached the galley-proof stage). I do recall that Gil was still a theoretical physicist at the time, in the U.S. but still relatively fresh from Havana, and he was most likely making his academic transition to film studies and film theory when we eventually met in New York. (See his Introduction to his magisterial 1998 The Material Ghost, “Film and Physics,” for more details.) Years later, circa the early 80s, we became neighbors in Hoboken, living only a few blocks apart, and we remained loosely in touch for the remainder of his life, during his various stints at William Paterson, Princeton, Harvard, Missouri, and, most permanently, Sarah Lawrence, where he ran the film history program.

A slow and methodical writer, but also a prolific one, Gil wrote frequently about film for the The Hudson Review, The Yale Review, and the London Review of Books and less often for film and academic journals, and I was often envious of the way he was both welcome and able to hold his own as a public intellectual with a literary sensibility in those and similar venues, such as The Nation. Read more

Written for the Fall 2015 issue of Film Quarterly. — J.R.

The Writers: A History of American Screenwriters and

Their Guild by Miranda J. Banks

This is clearly a creditable, conscientious, intelligent, and

useful book, but I feel obliged to confess at the outset that

I don’t feel like I’m one of its ideal or intended readers. The

subtitle loosely describes its contents, but “A Business

History of Hollywood Screenwriters and Their Guild”

would come much closer to the mark, even if it might make

the book less marketable to me and some others. And the

unexceptional simplification of the title and subtitle is part of

what gives me some trouble: it’s the business of Hollywood,

after all, to convince the public that “American screenwriters”

and “Hollywood screenwriters” amount to the same

thing. And the moment that any meaningful distinction

between the two collapses, then the studios, one might argue,

have already won the battle.

I don’t expect my own bias about this matter to be shared

by many of Film Quarterly’s readers. Writers who blithely

and uncritically toss about terms like “Indiewood” designed

to further mystify the differences between studio work and

independent work probably don’t think they’re working for

the fat cats, but from my vantage point as a journalist who

thinks that these distinctions deeply matter, they’re the worst

kind of unpaid publicists. Read more

I’m very glad that I recently purchased Saul Bellow’s collected nonfiction — a handsome, interesting, and useful book, even if I tend to regard Bellow as the most overrated of all the “major” contemporary American novelists (certainly talented and smart, but not terribly interesting when it comes to formal inventiveness). And among the many valuable discoveries to be made here is the fact that Bellow served as a film critic for the magazine Horizon in 1962-1963, a stint which yielded four separate columns — on Morris Engels’ Lovers and Lollipops, on Luis Buñuel’s Viridiana, and two think pieces, “The Mass-Produced Insight” (which quotes from his pal Manny Farber) and “Adrift on a Sea of Gore” (mostly about Richard Fleischer’s Barrabas).

I’m very glad that I recently purchased Saul Bellow’s collected nonfiction — a handsome, interesting, and useful book, even if I tend to regard Bellow as the most overrated of all the “major” contemporary American novelists (certainly talented and smart, but not terribly interesting when it comes to formal inventiveness). And among the many valuable discoveries to be made here is the fact that Bellow served as a film critic for the magazine Horizon in 1962-1963, a stint which yielded four separate columns — on Morris Engels’ Lovers and Lollipops, on Luis Buñuel’s Viridiana, and two think pieces, “The Mass-Produced Insight” (which quotes from his pal Manny Farber) and “Adrift on a Sea of Gore” (mostly about Richard Fleischer’s Barrabas).

I was especially interested in Bellow’s appreciative remarks about Buñuel. But here is where the attentions of his otherwise careful editor, Benjamin Taylor, come up woefully short. Listing some of the more notable items in Buñuel’s filmography, Bellow comes up with two very puzzling titles, The Roots (1957) [sic] and Stranger in the Room (1961) [sic]. The second of these, which he discusses in some detail, sounds like he might be thinking of La Fièvre Monte à El Pao (1959), while the first is most likely La Mort en Ce Jardin (1956). Read more

I hadn’t originally intended to watch this film again, for the umpeenth time, when it was shown late last night on Turner Classic Movies, but as soon as I noticed the exquisite tinting and the (uncredited but fabulous) music score on the print they were showing, I couldn’t resist. (Apparently — or at least hopefully — the same print is available for online viewing.)

I can’t think of another film in the history of cinema in which hands are more expressive, in a multitude of ways — a motif that may be even more telling than the gradual evolution of Mac and Trina’s wedding photo, half of which eventually becomes the wanted poster for Mac’s arrest.

Too much of the writing about Greed (mine included) has been concentrated on the legend of the filming and the subsequent cutting and not enough about what remains, entirely visible and triumphant, in what remains and is fully visible.

A lot has been written about the relationship between the fates of Greed and The Magnificent Ambersons in terms of their eviscerations, and not enough about the major differences between the ways that they’re edited in their surviving forms.(Perhaps the most neglected but significant common point between the films is the unerring sense of camera angles in the staging of both films.) Read more

Written for and published by Slate on December 27, 2005. The other contributors to this discussion, whom I’m addressing, are David Edelstein, Scott Fondas, and A.O. Scott. — J.R.

From: Jonathan Rosenbaum Posted Tuesday, Dec. 27, 2005, at 2:13 PM ET

Holiday Greetings, David, Scott, and Tony, David, I appreciate your invitation to “shake hands and come out punching,” though I suspect our disagreements this time around may wind up having more to do with Steven Spielberg and Munich than they do with Terrence Malick and The New World. (See Edelstein’s top-20 list of 2005 films here.) Just to be contrary, however, let me start off with four agreements. Me and You and Everyone We Know, The Three Burials of Melquiades Estrada, William Eggleston and the Real World, and Homecoming all belong somewhere on my own extended list of favorites — and I’d need an asterisk of my own for the penultimate title, David, because Michael Almereyda is a friend whom we share. Read more

Check out Chris Fujiwara’s just-posted article at Moving Image Source, comparing audience responses to Douglas Sirk movies in Japan and the U.S.–a fascinating read. [8/18/09] An update, one month later: Fujiwara’s article on Jacques Tourneur’s Stranger on Horseback on the same site, which just prompted me to order and see the DVD, is also highly recommended. [9/18/08]

Read more

Each year, film critics gather in Slate‘s “Movie Club” to kvetch about the year in movies. This year, Slate‘s David Edelstein is joined by Scott Foundas (LA Weekly), Jonathan Rosenbaum (Chicago Reader), and A.O. Scott (the New York Times).

Each year, film critics gather in Slate‘s “Movie Club” to kvetch about the year in movies. This year, Slate‘s David Edelstein is joined by Scott Foundas (LA Weekly), Jonathan Rosenbaum (Chicago Reader), and A.O. Scott (the New York Times).