From the Chicago Reader (March 11, 1988). —J.R.

THE MANCHURIAN CANDIDATE

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed by John Frankenheimer

Written by George Axelrod

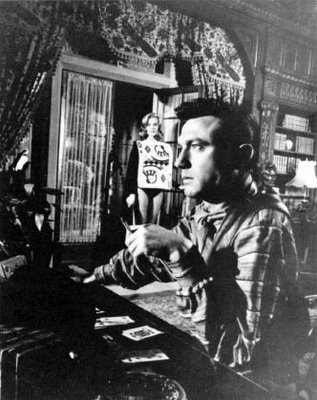

With Frank Sinatra, Laurence Harvey, Janet Leigh, Angela Lansbury, James Gregory, Leslie Parrish, John McGiver, Khigh Dhiegh, and James Edwards.

The first and only time I’ve seen a good 35-millimeter print of Carl Dreyer’s 1944 masterpiece Day of Wrath was in Europe about a month ago. The film was being rereleased, along with Dreyer’s 1925 Master of the House and his 1955 Ordet, at several small theaters in Paris, and the difference in seeing it in optimal conditions was incalculable. The carnal impact of the film’s sound track, lighting, compositions, camera movements, and performances may be dimly evident in duped 16-millimeter prints and on video, but the overall effect is like that of viewing a great painting through several layers of gauze, or hearing a great symphony through earmuffs. By and large, this prophylactic experience is the only way our film heritage is preserved for most people in the U.S. — which is another way of saying that it isn’t really preserved at all.

Why are major rereleases of old movies in spanking new prints — apart from Disney cartoon features, and the five Hitchcocks that resurfaced a few years back — such a rare occurrence in this country, and so common in France? (I’m not only thinking of Dreyer: the last times I saw new prints of The Shop Around the Corner and Gentlemen Prefer Blondes were in Paris, too.) Perhaps Mary McCarthy was onto something when she noted that “the only really materialistic people I have ever met have been Europeans,” and that “the strongest argument for the unmaterialistic character of American life is the fact that we tolerate conditions that are, from a materialistic point of view, intolerable.” I doubt that the French are any smarter than us, but there’s plenty of evidence that they know more about how to enjoy themselves: they can even find pleasure in art.

So it’s an event of some importance that MGM/UA has decided to rerelease The Manchurian Candidate, an uncommonly pleasurable (which includes exciting, unsettling, funny, provocative, and mind-boggling) black-and-white feature of 1962 that can only receive its maximal impact on a big screen. The pretext for this rerelease is that the movie has long been unavailable because its star, Frank Sinatra, purchased the rights in the early 70s in order to keep the movie under wraps. At the suggestion of critic Richard Corliss, it was unearthed at the last New York Film Festival, and the enthusiastic responses to it convinced MGM/UA to give it a limited run in a few major cities.

There has been a lot of speculation about why Sinatra shelved the film in the first place. Most theories connect the move to his friendship with John F. Kennedy. When Arthur Krim — the former president of UA, who was also the Democratic party’s national finance chairman at the time — balked at making the film, which seemed to him too politically volatile, Sinatra persuaded Kennedy, a fan of the Richard Condon novel the script was based on, to intervene on behalf of the project. The subsequent Kennedy assassination may have triggered some feelings of guilt on Sinatra’s part, for the film includes a political assassination (and Sinatra had already played a would-be presidential assassin in the 1954 thriller Suddenly); another motivation may have been his own later political shift from the left to the right.

It’s a movie whose subversive, offbeat, and ambiguous overtones have never fully received their due, here or anywhere else. Ironically, while it is as “advanced” for its period as many of the films of the French New Wave — and qualifies as a kissing cousin of that movement, much as Michael Powell’s 1960 Peeping Tom did in England — it appears that the French critics missed the boat on this one entirely, perhaps in part because it couldn’t be adequately accounted for in auteurist terms as “un film de John Frankenheimer.” Critics as diverse as Andrew Sarris and Dwight Macdonald treated it with contempt in 1962, and even Pauline Kael, who was possibly the movie’s biggest American champion, never devoted more than a few sentences to it. Despite a few appreciations in film journals, screenwriter and coproducer George Axelrod was probably at least half-right when he noted in 1968 that “it went from failure to classic without ever passing through success” — a fate that also befell many of Orson Welles’s best features, for reasons that may not be entirely coincidental.

Indeed, when I first saw the movie as a college sophomore, it was Citizen Kane that the film initially brought to mind. Not that it was as good, or that it represented a comparable directorial debut; Frankenheimer was riding high at the time, but he already had four features under his belt — two of them released the same year as The Manchurian Candidate — after a prolific period as the best director of live TV dramas for Studio One and Playhouse 90 (which roughly paralleled Welles’s earlier work as a stage and radio director).

What seemed most Wellesian about the movie were aspects of the camera, editing, and acting styles — including uses of chiaroscuro, wide angles, deep focus, shock cuts, and overlapping dialogue — as well as how mercurial and unpredictable the overall movement was. It started out as a war film, veered into political satire (with touches of Kazan-like family melodrama — complete with a David Amram score — and pseudo-documentary), and took on elements of paranoid science fiction, black comedy, suspenseful intrigue, and horror. After various side trips into straight action (an all-stops-out karate fight), existential psychodrama with arty trimmings, and alternately straight and parodic versions of lush Hollywood romance, it finally settled into the pacing of a thriller, before ending with a phony scene that exuded patently unfelt patriotic soap opera. Yet despite all these disconcerting mixtures and gear changes, the narrative remained fluid and gripping throughout.

Less Wellesian were the film’s cavalier treatments of period and character. The film is set in 1952-1954, and a lampoon of Joseph McCarthy figures prominently in the plot, but hardly any effort is made to re-create the period. The handling of character — which seems largely predicated on the premise that a use of big-name stars enables an audience to slide over incongruities — is a good deal weirder. The initial meeting of Frank Sinatra and Janet Leigh on a train, for instance, provides one of the strangest examples of “meeting cute” on record:

Leigh: “Maryland’s a beautiful state.” Sinatra: “This is Delaware.” Leigh: “I know. I was one of the original Chinese workmen who laid the tracks on this stretch. But nonetheless, Maryland’s a beautiful state. So is Ohio, for that matter.” Sinatra a bit later: “Are you Arabic?” Leigh: “No. Are you Arabic?” Sinatra: “No.” Leigh: “Let me put it another way. Are you married?”

The fact that by the time of their second short meeting, Leigh has already returned her fiance’s engagement ring and declared her unlimited devotion to Sinatra is handled just as blithely as the fact that Sinatra is portrayed as a voracious intellectual bookworm, or that Laurence Harvey plays an American with an unexplained English accent, or that Leslie Parrish, the other female romantic lead, who played Daisy Mae in the 1959 L’il Abner, and portrays a liberal senator’s daughter here, is shown without any overt irony as a nearly equivalent sort of bimbo. In short, the movie plays on standard Hollywood clichés as if on a grand organ — delivering most of them deadpan, but mixing and altering them so adroitly that they often come out as surreal gibberish.

I haven’t yet said anything about the movie’s central plot, and because it depends on a good many twists and surprises, readers who haven’t yet seen the film are invited to step off here, and not come back until they have. The story exists in a sort of parallel universe inspired by paranoid right-wing fantasies of the period — including the notion that Russian and Chinese Communists are working jointly at a scheme to take over the U.S. via inside stooges and the theory that brainwashing techniques have developed to the point where prisoners can even be programmed to kill their own loved ones against their own conscious wills.

Two major instruments in this scheme are a captured U.S. officer (Laurence Harvey) and his stateside stepfather, an alcoholic, pea-brained, McCarthy-like demagogic senator who is controlled by Harvey’s conniving and powerful mother (Angela Lansbury), who turns out to be an agent for the Reds. Harvey’s hatred for his emasculating mother is an integral part of his brainwashing, keyed to the queen of diamonds in a pack of playing cards. We eventually learn that her hypnotic control over her son includes incest, and her desire for ultimate power is currently motivated less by Communism than by a desire to take revenge on her fellow Communists for brainwashing her son.

The dizzying complexities of this Freudian scenario, halfway between Greek tragedy and lurid comic book, are worked out brilliantly on the level of exposition, but they can’t be subsumed under a responsible or coherent political position. (Elsewhere, Frankenheimer and Axelrod have both come across as liberals.) The politics of the movie are in fact a kind of shadow play, manipulated like the Hollywood cliches for the sake of jazzy effects, just as the characters function basically as dream figures. None of it begins to make sense on reflection as part of a coherent universe. But the remarkable achievement of Axelrod and Frankenheimer — who coproduced the movie, and seem to have worked with an unusual amount of freedom — is to use the characters and politics to set certain narrative mechanisms in motion, and to make us accept them as if they were both coherent and believable. And, as a significant side benefit, they expose the deceptive mechanisms of political and Hollywood mythmaking in general.

The film’s method becomes most apparent in two matching tour de force set pieces, which occur almost consecutively fairly early in the film. Each scene is structured around a different kind of discontinuity and disorientation, and each makes an ironic commentary on the film as a whole by commenting on the deceptiveness of a particular kind of public spectacle.

The first set piece is a recurring nightmare dreamt by Sinatra’s character, a former member of Harvey’s captured patrol, which we gradually discover is the memory of a real event in Manchuria distorted by hypnotic suggestion — a public demonstration by a Chinese Pavlovian (Khigh Dhiegh) to his colleagues of the successful brainwashing of Harvey and his men, which culminates in Harvey murdering two of his own men under the Pavlovian’s orders.

Meanwhile, the American soldiers onstage have been hypnotized and think they’re attending a ladies’ garden club meeting in New Jersey; a 360-degree pan around the lecture hall begins with this incongruous delusion, only to arrive at the real meeting before the end of the camera movement. Thereafter, the film cuts back and forth between and gradually merges the two parallel versions of the event, and the one disquieting constant in this sequence, apart from the continuity of the lecture itself, is our identification figures, the soldiers themselves — figures who are at once the focus of the spectacle and spectators themselves. The fact that they’re all drugged and hypnotized makes them our surrogates in another way: they’re passive spectators, unable to exert any control over the proceedings. The question of their moral responsibility for what is happening remains as troubling and as uncertain as our own relation to what we’re seeing. (Later, this queasy ambivalence becomes concentrated on Harvey’s career in the States as a brainwashed assassin: his powerlessness to affect or guide his own actions matches our own impotence as spectators.)

Sandwiched between this Manchurian set piece and its subsequent continuation (when a black soldier in the patrol, played by James Edwards, has the same nightmare, with black garden-club ladies replacing the white ones) is another public hearing, set in Washington, D.C., where Sinatra is again present, this time as a press secretary. The scene is a televised press conference given by a U.S. Cabinet member, which erupts into pandemonium when Harvey’s stepfather (James Gregory) restages the witch-hunting debut of Joseph McCarthy by claiming to have a list in his hand of 207 “known” card-carrying Communists working for the Defense Department — a figure that later gets amended to 104, then 275, and finally 57.

Here the discontinuity of action and the spectator’s disorientation is controlled by the TV monitors transmitting the event — a personal touch of Frankenheimer’s, with his extensive background in live TV — which show the same events occurring simultaneously from different angles. [2010 postscript: the same technique is employed at the beginning of Frankenheimer’s brilliant 1957 TV drama for Playhouse 90, The Comedian.] Once again, spectacle and spectator become confused, although here spectatorship becomes anything but passive — the anger and aggression displayed on both sides gives the scene the temperature of a near-riot.

Gregory and the Cabinet member are situated at opposite ends of the hall, with a crowd of reporters and technicians and TV monitors, cameras, and other equipment between them, and Frankenheimer creates an intricate spatial confusion in his various ways of juggling and juxtaposing these elements. At one point, we see Lansbury, the power behind Gregory, hovering over his image in diverse frontal angles on one of the monitors in the foreground while Gregory himself is visible in profile in the background. (The predatory relation of Lansbury to her puppet husband recalls the famous shot in Citizen Kane of Agnes Moorehead calling out the window to her little boy in the snow, just as she’s signing his life away to a banker. By replacing the window frame with a TV monitor, the film points up how much Lansbury’s control over events hinges on her control over media images.)

At another point, a different monitor closer to the stage alternately shows the Cabinet member, from a separate angle, and Gregory screaming back at him. Perhaps the most complete sense of disorientation is reached when Gregory is seen pointing his arm in one direction while a reverse angle of him on a monitor shows him pointing in the opposite direction — a prefiguration of the movie’s eventual collapse of any distinction between the political left and right on the level of plot.

The unreliability of visual evidence and the tendency of appearances to deceive is the common element in these two set pieces, and a fundamental principle behind the film’s paranoid scenario, which gradually — and literally, in the climactic chase sequence — describes the overall shape of a labyrinth. Carrying the same principle further, the movie confuses us emotionally and conceptually as well as visually by playing related tricks with dramatic and generic conventions. It’s typical of the movie’s playful use of diverse kinds of political and patriotic rhetoric that the climactic race to stop a political assassination in Madison Square Garden gets stalled interminably by a playing of the national anthem. Prior to this, after building up a great deal of sympathy for the father of Harvey’s girlfriend — a courageous and principled liberal senator, played with a lot of charisma and poise by John McGiver — the film treats his cold-blooded murder as a kind of bad-taste, antiliberal joke: the bullet that kills him passes first through a milk carton in his hand, and before he drops dead, milk gushes out.

With an equal amount of perversity, Gregory is linked visually on at least three separate occasions to Abraham Lincoln; busts and portraits of Honest Abe are as plentiful in his and Lansbury’s house as queens of diamonds are in the movie. And the sinister Chinese Pavlovian, with his quaint bourgeois taste and his habit of cracking corny jokes, is made to seem as cuddly as a Dickens eccentric. Visual and verbal non sequiturs abound: in perfect Sinatra-ese, Sinatra describes at one point having “a real swinger of a nightmare”; at a costume party, Lansbury is dressed as Mother Goose, and after Parrish comes dressed as the queen of diamonds, the movie goes out of its way to “explain” this as a totally outrageous coincidence.

The point about this latter absurdity is that Axelrod could quite easily have worked a logical explanation for this into the dialogue — the script is anything but lazy — but preferred to flaunt the contrivance here, as he does in the first two scenes between Leigh and Sinatra. (It’s been many years since I’ve read Richard Condon’s novel, but if memory serves, the calculated goofiness of such details is nearly always Axelrod’s contribution. Although the original’s plot is certainly baroque enough to begin with — and is even more explicit about such matters as the mother-and-son incest — the movie embroiders it further with a more irreverent style.) Going beyond mere excess, the movie gives some poignancy to Sinatra’s line, “I could never figure out what that phrase meant, “more or less”‘; by the time the end title appears, most spectators won’t be able to figure it out either.

Alternately using and ridiculing all the Hollywood-Pavlovian techniques at its disposal, The Manchurian Candidate actually succeeds in making us care about its deliberately cardboard characters when it isn’t pulling the rug out from under us in order to prove how easily we can be brainwashed, too. Lansbury and Harvey have never been better: the former, in particular, is pure sulphuric acid and brimstone, while the latter’s feline priggishness eventually gives way to a moving sense of pain that can be found nowhere else in his work. The supposedly saner performances of Sinatra and Leigh are no less crucial in establishing our relation to the other two. As improbable as Sinatra and Leigh are, they function rather like Lockwood and Nelly Dean in Wuthering Heights — as “normal” lenses framing the mad incestuous couple, square witnesses obliging us to fill in the blind spots in their viewpoint, thereby participating in the demonic creation.

Exhilarating and often terrifying in its prodigal and gleeful invention, as well as its varied kinetic pleasures, the film is also sufficiently serious about its inspired mischief to give us a lot more to think about than any roller-coaster ride devised by Lucas or Spielberg. If 1988 Hollywood gives us a movie half as good as this one, we have quite a year in store.