From the Chicago Reader (March 3, 1989). — J.R.

NEW YORK STORIES

*** (A must-see)

“Life Lessons”

Directed by Martin Scorsese

Written by Richard Prince

With Nick Nolte, Rosanna Arquette, and Patrick O’Neal.

“Life Without Zoe”

Directed by Francis Coppola

Written by Francis Coppola and Sofia Coppola

With Heather McComb, Talia Shire, Giancarlo Giannini, Don Novello, and Selim Tlili.

“Oedipus Wrecks”

Directed and written by Woody Allen

With Woody Allen, Mae Questel, Mia Farrow, and Julie Kavner.

With the exception of the recent and disappointing Aria, there have been no films made of late that consist of thematically related sketches, compilations of episodes by one director or more. New York Stories may help make the form fashionable again. The arbitrariness of the standard running time of features, at least from an artistic standpoint, makes a good many movies needlessly padded and a few others shorter than they should be, while the difficulty in marketing shorts discourages most commercially established filmmakers from even attempting to work in the form. New York Stories came about because Woody Allen wanted to make a short and decided that incorporating it within an anthology would make it commercially feasible.

The usual argument made against sketch movies is that they’re invariably uneven — which is true enough but also rather beside the point. (If the same argument were made in publishing, we’d never have any collections of short stories.) Sketch movies by a single director, like Julien Duvivier’s Tales of Manhattan (1942), John Ford’s The Rising of the Moon (1957), Roger Corman’s Tales of Terror (1962), and Woody Allen’s own Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Sex (but Were Afraid to Ask) (1972), theoretically minimize the lack of balance, although these usually turn out to be uneven as well. (It will be interesting to see whether Jim Jarmusch’s Memphis-based sketch film, which is currently in the works, will be able to avoid this problem.)

When a sketch movie involves different directors, which happens more often, the issue of overall unity becomes more prominent. Sometimes the unity is supplied by a single author, such as Somerset Maugham in Quartet (1949) and Trio (1950) and Edgar Allan Poe in Spirits of the Dead (1968); sometimes it comes from a category like the seven deadly sins, which has already furnished three separate sketch features (one Italian and linked to the neorealists, one French and linked to the New Wave, and the last a more recent international effort directed exclusively by women). But perhaps the most interesting sketch features by different directors are those that are unified by subtle and secret factors as well as more blatant ones. My favorite example of this subgenre, The Story of Three Loves — directed by Gottfried Reinhardt and Vincente Minnelli for MGM in 1953 — is linked together not only by the common ground implied by the title, but less obviously by the impact of European existentialism on Hollywood in the early 50s.

New York Stories is another good example of a sketch movie whose unity goes beyond the linkage of its title (three stories with a New York setting), although it’s hard to say how much this came about through chance and how much of it was determined by design. The three sketches, made respectively by Martin Scorsese, Francis Coppola, and Woody Allen, concern parental and sexual relationships and the relation between the two; and all three are involved in one way or another with middle age — which isn’t surprising considering the present ages of the directors (Scorsese is 46, Coppola is 49, and Allen is 53).

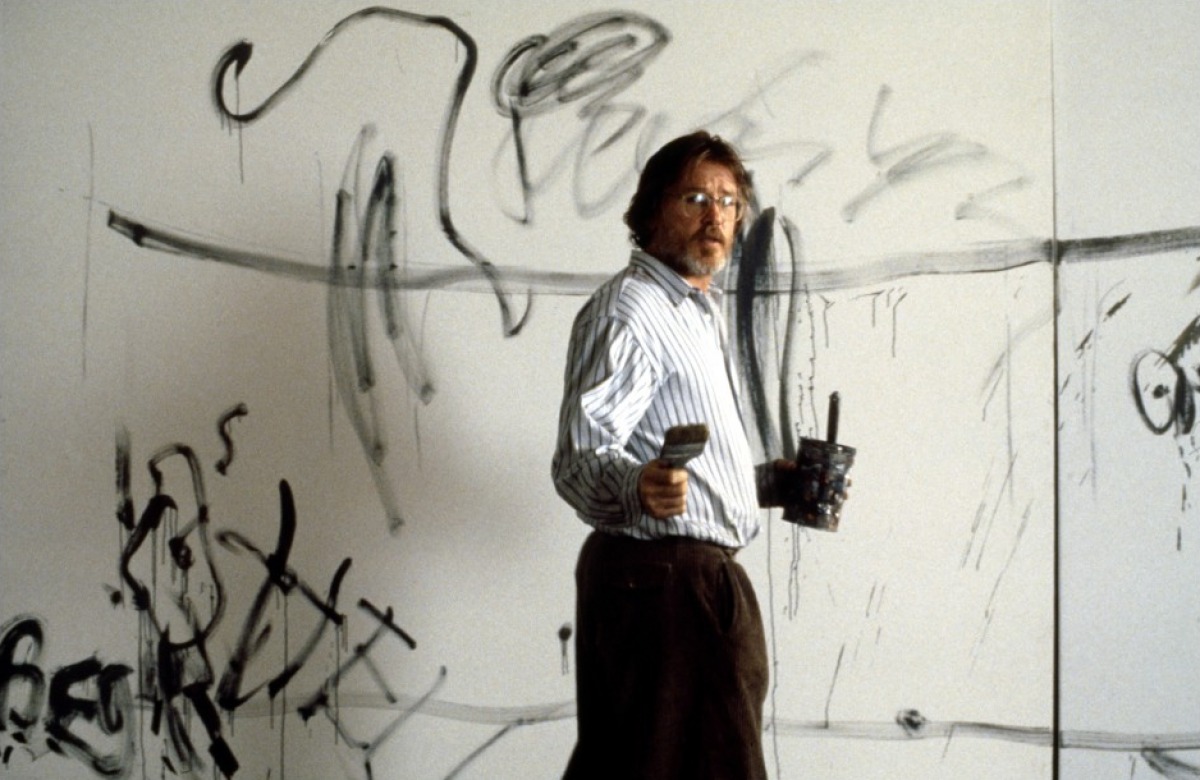

Scorsese’s “Life Lessons,” the first sketch, centers on the breakup of a successful New York painter named Lionel Dobie (Nick Nolte) and his apprentice and mistress Paulette (Rosanna Arquette), who is less than half his age. Inspired in part by Dostoyevski’s The Gambler, as well as by a diary and short story written by Dostoyevski’s young mistress (whose first name was Paulina), the film has a lot more in common with Scorsese’s earlier work (especially some of his movies with Robert De Niro, like New York, New York and Raging Bull) than it does with more recent efforts like After Hours, The Color of Money, and The Last Temptation of Christ. The nervously panning camera and jump-cut editing, the use of loud rock music, and the sudden swings from calmness to violence all serve to mark Dobie as a quintessential Scorsese hero, raging with energy and contradictions, and the depiction of his art making, which manages to be both precise and sensual, offers a much more plausible view of the New York art world than the superficial and parodic glosses found in After Hours.

Paulette, who is determined to break loose from Dobie sexually and is not at all certain about her own worth as a painter, remains in perpetual rebellion against him throughout the story; her own violent mood swings form part of the sketch’s dynamics, but it is basically Dobie’s craziness that determines the nervousness of the film style as he successively plunges into his work and then emerges from it like a writhing fish out of water, oscillating between father figure and would-be lover and back again. As in nearly all of Scorsese’s best work, it is the expression and presentation of the central character’s mania that give the story life — a kind of expressionism that in this case is directly tied to the flow and texture of Dobie’s painting — rather than the shape of the anecdote, which typically takes the form of a vicious circle.

The issue of encroaching middle age may be just as important to Francis Coppola’s “Life Without Zoe,” but in this case the anecdote skirts the issue and deals with it only obliquely, because the narrator and central character is a 12-year-old girl named Zoe (Heather McComb). The precocious daughter of a wealthy, semiestranged couple who usually aren’t around (Talia Shire and Giancarlo Giannini), she lives at the Sherry-Netherland Hotel and is taken care of mainly by the family butler (Don Novello). The elaborately contrived plot — which involves the nephew of an Arab king (Selim Tlili), a missing diamond earring, her father’s career as a successful flute player, and the eventual reconciliation of her parents — is ultimately less important than the style and mood of the sketch, which, as production designer Dean Tavoularis has pointed out, suggest “a kind of Noel Coward-like world for children” that has more to do with the 40s than it does with the present.

Coppola scripted this sketch with his 17-year-old daughter Sofia, who also designed the bizarre costumes (which, in the case of Zoe on a typical day at school, combine ragged jeans with a Chanel hat and jacket), and part of the overall incoherence of this segment undoubtedly comes from combining the romanticized views of New York conjured up by two generations 30 years apart. Coppola’s willingness to experiment certainly sets this sketch apart from those of Scorsese and Allen, but as with many of his other experiments — One From the Heart, Rumble Fish, Tucker — the results tend to be hit-or-miss rather than a concerted program aimed at a particular idea or effect, and the whimsy and archness here tend to work against the stylishness by raising too many irrelevant questions. (For instance what the glorification of wealth and wiseass children is supposed to mean above and beyond the telling of a fairy tale.)

The personal aspects of this colorful exercise, which mainly seem related to familial reconciliation and celebration, don’t always follow the same drift as the style, which verges closer to an “I love New York” commercial blended with a recitation by one of J.D. Salinger’s Glass children. The results are striking but a mite suffocating; ironically, we aren’t even permitted to imagine what “life without Zoe” might be like.

Woody Allen’s “Oedipus Wrecks” marks a welcome return to the fanciful comedy of the pre-art-house Woody as well as to the imaginative freedom of his best fiction — both of which are usually more directly Jewish in influence and subject than his more “serious” movies. Allen plays Sheldon Mills, a beleaguered hero who informs the camera (as well as his shrink) in the opening shot, “I’m 50 years old. I’m a partner in a law firm. And I still haven’t resolved my relationship with my mother.”

The part about the law firm proves to be mainly irrelevant; in contrast to the artistic professions of the first two sketches — painting and flute playing — Sheldon’s occupation is purely perfunctory, and Allen seems to use it only as a means for dramatizing his character’s overall uptightness. But both his age and his overbearing Jewish mother (Mae Questel) are very germane to everything that follows: his relationship to a gentile who has three children of her own (Mia Farrow), his therapy, his sex life, and his very state of mind. And when his mother mysteriously disappears in a magic-show act and then reappears in gigantic form over the Manhattan skyline, the fantasy premise follows logically and naturally from the psychological premise: it is merely Sadie’s overbearingness assuming a more concrete and public form.

Allen’s reversion to the style and tone of his earlier comedies isn’t quite complete, any more than Scorsese’s return to his sources in “Life Lessons” negates the lessons learned from his more recent work. The use of nostalgic pop tunes here is every bit as central as it is in September and Another Woman, and the final tune used, which I won’t divulge, actually illustrates the end of his fable with a literalism that goes well beyond any of his previous uses of musical cues. Similarly, Allen milks a final, extended close-up of himself well beyond the duration that he would have permitted in any of his critical self-portraits prior to Manhattan, although he arguably comes closer to justifying that conceit in this context than he has in all his intervening work. At least some of the other details — such as Farrow’s children by another marriage and Sheldon’s penthouse apartment — seem every bit as self-referential as anything in the Coppola sketch.

In his Paris Review interview, William Faulkner suggested that “maybe every novelist wants to write poetry first, finds he can’t, and then tries the short story, which is the most demanding form after poetry. And, failing at that, only then does he take up novel writing.” Most filmic equivalents to poetry exist outside commercial moviemaking entirely, but by further analogy I think it’s fair to say that in some respects it’s harder to create a good movie short than a good movie feature.

The encouraging thing about New York Stories is that it shows all three directors testing and refining the strengths of their earlier work — with varying degrees of success, to be sure, but with a seriousness that still goes beyond that of many of their recent features. Nolte’s performance in “Life Lessons” is much richer than anything offered by Paul Newman in The Color of Money (and incidentally restores my faith in Nolte after John Milius’s camp exploitation of his machismo in the current Farewell to the King); Coppola’s glittery, romantic view of Manhattan in “Life Without Zoe,” whatever its limitations, still to my mind surpasses in inventiveness his efforts in The Cotton Club; and Allen’s “Oedipus Wrecks” finally gives us back a Woody Allen that is in closer touch with his true gifts and insights.