From the Chicago Reader (March 24, 1989). — J.R.

LAWRENCE OF ARABIA

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed by David Lean

Written by Robert Bolt

With Peter O’Toole, Alec Guinness, Anthony Quinn, Jack Hawkins, Jose Ferrer, Anthony Quayle, Claude Rains, Arthur Kennedy, and Omar Sharif.

Thanks to a meticulous restoration carried out by Robert A. Harris and Jim Painten, working with a team of specialists that ultimately included director David Lean himself, Lawrence of Arabia has been rereleased in all its original glory in a version that includes some footage that wasn’t even seen by most of the film’s earliest audiences (the original road-show version, released in late 1962, was cut by about 20 minutes before it went into general release). I won’t dwell upon the complex detective work carried out by the restorers, except to note that in order to make the version currently playing as complete as possible, the original actors even redubbed some of their lines, which were then electronically altered so that their present voices would sound like their voices 27 years ago. Lean was also permitted to make a few minor modifications in the editing, so that the definitive version of this epic about the enigmatic T.E. Lawrence and his unorthodox military career is actually a “final cut” that incorporates practically all of the material that was in the original version.

Having seen the film only twice — once around the time that it first came out, and again recently — I find my feelings about it even more strongly divided than they were in the early 60s. To put things in perspective, 1962 was a year in which other prominent English-language releases in the U.S. included John Ford’s The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, Howard Hawks’s Hatari!, Vincente Minnelli’s Two Weeks in Another Town, Stanley Kubrick’s Lolita, John Frankenheimer’s The Manchurian Candidate, and Sidney Lumet’s Long Day’s Journey Into Night.

All of these movies seemed superior to Lawrence in one way or another back in 1962, and even today, I would still probably rank them all higher. Looking back at the spring 1963 issue of Film Culture — the same issue, incidentally, where the first version of Andrew Sarris’s highly influential auteurist manifesto, The American Cinema, appeared — I see in a chart of critics’ ratings of current releases that Sarris gave the lowest possible rating to Lawrence (“poor”), Peter Bogdanovich ranked it only a notch higher (“fair”), two other critics deemed it “very good,” and only William Everson and Dwight Macdonald considered it “excellent”; no one at all gave it the highest rating, which was “exceptional.”

This was of course during a period when the French New Wave was nearing the height of its glory, when Antonioni and Fellini were first acquiring mass appeal in the U.S., and when the New American Cinema was just beginning to make a pronounced impact — to cite only some of the excitement that made Lean’s achievement look relatively staid and conventional. Certain critics of this period like Macdonald, Stanley Kauffmann, and John Simon clearly thought otherwise, but because these same critics tended to disparage the majority of the movies that I cared most about (ranging from Ford and Welles to Godard and Resnais), it wasn’t difficult to take sides against Lean as the epitome of academicism, literary cinema, and “good taste” in the worst sense — all the signs of old-fashioned squareness that the best new movies were fighting against.

I find it hard to disavow the essential tenets of that position today. But something vital about the state of creativity in the cinema has changed since then, and compared with most recent releases, Lawrence of Arabia can only properly be regarded as a towering achievement (with certain reservations, which I will get to shortly). If its spectacular, formal use of 70-millimeter has none of the sense of the new to be found in such superior big-screen blockbusters as Tati’s Playtime and Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (both of which surfaced only five or six years later), it still marks a major step forward for the ambitious personal epic compared to such preceding examples of the period as Cecil B. De Mille’s The Ten Commandments, Stanley Kubrick’s Spartacus, Otto Preminger’s Exodus, Nicholas Ray’s King of Kings, and Lean’s own The Bridge on the River Kwai. In addition, Lawrence of Arabia has proved to be an enormous influence on subsequent epics. The ambiguous positioning of its central character clearly paved the way for Patton, the use of a naive reporter as an expositional device was later adopted (albeit clumsily) in The Green Berets, and still other aspects of Lawrence of Arabia have found their way into subsequent epics ranging from Star Wars to Apocalypse Now to Dune.

Part of the unusual achievement of Lawrence of Arabia in its time, later emulated by such would-be successors as A Man for All Seasons and Becket, was to combine the purely sensual virtues of a scenic and pictorial costume epic like one of De Mille’s with the more literary and “classy” cultural values of the English theater. (When Lawrence compares himself at one point to Moses crossing Sinai, the reference to The Ten Commandments becomes explicit; a little later, the film parodies this notion when Lawrence mistakes a dust storm for a “pillar of fire.”)

Ironically, although detractors such as Sarris called the film “impersonal” in the 60s, it can be seen today as one of the prototypes of the contemporary “personal” blockbuster in which the director’s own will to power is reflected in the ambiguous megalomania of the central character. This is a tradition that actually goes all the way back to such silent classics as Stroheim’s Foolish Wives as well as to The Ten Commandments and Hawks’s underrated Land of the Pharaohs. But Lean gave an increased intellectual respectability to this position that countless later directors have cashed in on, including, among many others, Werner Herzog (Aguirre: The Wrath of God), Francis Coppola (Apocalypse Now), Steven Spielberg (Close Encounters of the Third Kind), and more recently Martin Scorsese (The Last Temptation of Christ), John Milius (Farewell to the King), and Terry Gilliam (The Adventures of Baron Munchausen). Thanks in part to Lean’s example, these films are about more than their ostensible subjects — they are also about the positions of their respective directors in leading hordes of people, dreaming big dreams, and reflecting on the metaphysical ambiguities of their power, all of which has tended to make most of these blockbusters bear an annoyingly monotonous and narcissistic resemblance to one another.

It is to the credit of Lean and screenwriter Robert Bolt, however, that Lawrence of Arabia has a historical density and political and psychological nuances that go beyond those of its numerous successors. This is all the more surprising when one considers that, apart from Lawrence’s death in 1935 from a motorcycle accident, which opens the film, the time span covered in 216 minutes is only about two years — from the end of Lawrence’s stint as a lieutenant and mapmaker in Cairo in 1916, when he was dispatched to meet with Prince Faisal, until his return to England in 1918. Apart from the occasional allusion to Lawrence’s background, this leaves about 45 years in his life unaccounted for.

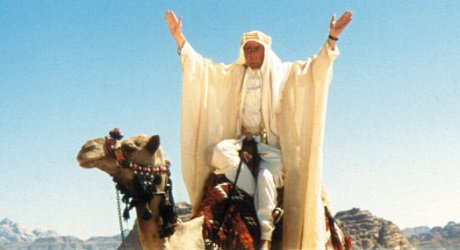

From the outset, Lawrence (Peter O’Toole) is perceived as a grand enigma: well-educated, self-assured, remote, oddly masochistic, and passionate about Arabia. Before very long, he emerges as a visionary leader of Arab independence against the Turks — winning the confidence of both Sherif Ali (Omar Sharif) and Prince Faisal (Alec Guinness) — and so impresses the bedouin army with his courage and endurance during a long trek across the desert to capture Aqaba that they garb him in Ali’s white burnoose, which henceforth becomes his identifying costume. He even wins over the wily and primitive Auda Abu Tayi (Anthony Quinn), drawing him and his men away from their loyalty to the Turks and into the bedouin army.

My knowledge of the real-life counterparts of these characters and events is spotty at best, but it seems to me that the film’s mythic dimension in relation to the third world is very closely allied to that of Apocalypse Now — the white man lording it over noble (or ignoble) savages, who look to him for guidance. This is certainly reflected in the characteristic decision to have two of the three leading Arab characters played by whites (Guinness and Quinn), and my reservations were recently seconded in an interesting and not entirely unsympathetic article about the film by Edward W. Said — literature professor at Columbia, author of Orientalism, and a member of the Palestine National Council — in the February 21 issue of the Wall Street Journal entitled “‘Lawrence’ Doesn’t Do Arabs Any Favors.”

Describing Guinness’s Faisal as “a cross between his rendition of Fagin and T.S. Eliot’s Confidential Clerk, with an annoying admixture of oiliness thrown in for good measure,” and Quinn’s Auda as “a semi-moronic thug out of West Side Story,” Said also argues that, contrary to the film’s depiction of its hero, “Lawrence was a British imperial agent, not an innocent enthusiast for Arab independence,” and a Zionist to boot. Focusing on the scene of the Arab National Council Meeting in Damascus, occurring near the end of the film, which Said rightly calls “the film’s political payoff, its climactic argument about the Arab revolt,” he persuasively concludes that Lean’s “unmistakably imperialistic” vision is that “serious rule was never meant for such lesser species, only for the white man.”

None of this should imply that Lawrence of Arabia is necessarily any more imperialistic or racist in its implications than other big-budget war epics; on the contrary, I would argue that it more or less goes with the territory. (In fact, one can find a pretty close equivalent to Lean’s depiction of the Arab National Council Meeting in Elia Kazan’s Viva Zapata! made ten years earlier, when the “nonwhites” who are shown as unfit to rule themselves — including the same uncouth Anthony Quinn — are Mexican peasants.)

Having acknowledged this serious limitation about Lawrence of Arabia, which may have contributed as much to its success as its more defensible virtues, I should mention what makes the film a major work in spite of these nagging problems. Freddie Young’s Super Panavision, 70-millimeter cinematography, for starters, is conceivably the greatest desert photography that we have in movies, and some of the film’s greatest moments are elongated meditations on mountains, camels, and mirages — moments that give us a sense of space, history, and even psychology that goes beyond any of the particulars found in Bolt’s extremely literate dialogue. (Another central visual reference point is the blueness of O’Toole’s eyes, which becomes all the more striking in relatively monochromatic desert settings.)

Excepting the minstrel-show casting of Faisal and Auda, the performances are virtually flawless: O’Toole has certainly never been better, and arguably Sharif and Jose Ferrer are at their best as well. (On the other hand, whether or not Ferrer’s depiction of a Turk is as objectionable as Guinness and Quinn’s Arabs — an issue that Said seems content to overlook — is a question worth raising.) At the same time, the performances are enhanced by the broader context created as the film alternates between actorly dialogue scenes and large-scale spectacle without giving the impression that either of these is padding. Even if some of this film’s strength comes from the acting and dialogue of the English theater, it can never be accused of looking stagy.

Returning to the question of Lawrence’s character, the film manages to suggest his ambiguous sexuality without ever committing itself to a specific reading of it. Some of this is no doubt due to actual or anticipated censorship restraints circa 1962. While little is known conclusively about Lawrence’s sexual orientation, most accounts agree that he was obsessed and traumatized by what happened to him after he was captured by the Turks in Deraa, which apparently included torture and homosexual rape. The film manages to be unusually explicit about the sexual interest of the head Turk (Ferrer) in Lawrence, but then it goes to great lengths to suggest that all that Lawrence suffered at the hands of the Turk and his henchmen was beatings. Much earlier, there’s a fairly strong suggestion of an amorous relationship between Lawrence and a young Arab servant, but this too is allowed to go nowhere.

The latter portion of the film charts a steady deterioration in Lawrence’s stability and self-confidence after the episode in Deraa, but both the nature of this change and the reasons behind it are left ambiguous, apart from Lawrence’s dawning recognition that he is more a pawn of British interests than an autonomous leader of the Arabs. This multilayered portrait suggests that Lean and Bolt are trying to at least partially demystify Lawrence as a hero, but the fact remains that the ideological baggage carried by the White Man’s Burden theme is a lot stronger than any amount of irony that the filmmakers can bring to it.

Indeed, some of the film’s irony has a sense of self-protection about it. Jackson Bentley (Arthur Kennedy), the American journalist modeled on war correspondent Lowell Thomas, is sufficiently disingenuous and cynical to imply a certain amount of anti-American satire in the portrait. But as Said points out, Bentley’s role in publicizing Lawrence isn’t all that different from the role of Lean and Bolt (are American newspapers any more “commercial” than big-screen blockbusters?) and Bentley seems to be used as a scapegoat to distract us from the comparable simplification being perpetrated by the filmmakers.

“They hope to gain their freedom,” Lawrence says to Bentley about the Arabs. “They’re going to get it, Mr. Bentley. I’m going to give it to them.” The irony here may be rebounding on Lawrence, and it’s worth noting here and elsewhere that the question often arises as to who is simplifying what and whom. (Bentley’s interview with Prince Faisal, by the way, which occurs shortly after the intermission, is one of the longer scenes not previously seen in its entirety in all the shorter versions of the film; it is also one of the few moments in the restoration when the sound seems slightly off.)

Magisterial, intelligent, handsome, mysterious, proud, brilliant, imperialist, bombastic, narcissistic: the film, like its hero, is all these things. Paradoxically, it is not really a film that admits hidden depths — the ironies and ambiguities are all there on the surface, which is one of the reasons I doubt that this is a masterpiece that can be combed indefinitely for buried treasures.

Lawrence prancing about on top of a captured train makes for some fine images, but not ones that tell us anything new or different about him; Lawrence half-crazed and soaked in blood may make us think of Shakespeare, but it’s the Classics Illustrated version. When we last see him riding off in a jeep toward his trip back to England and a motorcyclist passes him, reminding us of his eventual death, the effect is anything but complex; it suggests, rather, the kind of Profundity 101 that some English professors love to foist on helpless undergraduates.

On the other hand, it is pointless to complain that the charge of the bedouins on horses and camels into Aqaba is ahistorical (apparently the port fell to the Arabs without a single shot being fired) because a more accurate depiction would have deprived us of a stunning extended pan across the city to the sea during the battle, with a cannon grandly appearing in the center foreground as the camera comes to rest. I haven’t the foggiest notion of whether Lawrence’s grand entrance at the officer’s bar in Cairo wearing his white burnoose with his young Arab servant in tow is historically accurate, but it makes for a terrific scene, and Lean manages to stretch it out for maximum effectiveness. There are many such showstoppers all the way through, which prompts me to concede that as a grand, old-fashioned entertainment, Lawrence of Arabia qualifies, warts and all, as the best new movie around.