From the Chicago Reader (March 30, 1990). I must confess that I was disappointed for a long time that none of Campion’s subsequent films lived up to the promise of Sweetie, in spite of the virtues of some of them, at least until her wonderful 2014 miniseries Top of the Lake, which I’ve just belatedly caught up with. (I’ll never forget a bitter comment Jean-Luc Godard made to me in Toronto in 1996, citing Campion as a perfect example of a talented filmmaker “completely destroyed by money”.) But then again, to cite someone cross-referenced in this review (and also significantly cross-referenced in Top of the Lake, a kind of feminist response to Blue Velvet and Twin Peaks), it’s also hard to think of many David Lynch films that have lived up to the promise of Eraserhead, at least prior to Inland Empire….I suspect that the collaboration of writer Gerard Lee on Passionless Moments, Sweetie, and Top of the Lake has something to do with what makes all three of them stand out so vividly in Campion’s oeuvre.– J.R.

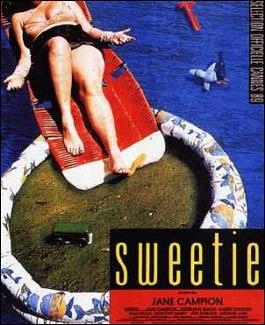

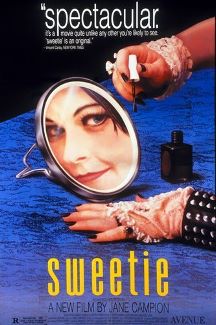

SWEETIE

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Jane Campion

Written by Gerard Lee and Campion

With Genevieve Lemon, Karen Colston, Tom Lycos, Dorothy Barry, Jon Darling, Michael Lake, and Andre Pataczek.

Sometimes the arrival of a major talent is greeted by immediate fanfares; but truly original talents, who often start well ahead of their audiences, sometimes have to wait things out. Even after three viewings spread out over half a year, I’m still racing after Jane Campion’s mind-boggling Sweetie, and I can’t claim fully to have caught up with it yet; it keeps bolting and veering off with a mind and will of its own — one strong indication that it’s still very much alive and dangerous.

Sweetie is the first theatrical feature by Campion, a New Zealand-born filmmaker now in her mid-30s. She attended college in Australia, studying painting, sculpture, and anthropology (her favorite teacher was a student of Claude Levi-Strauss), then went on to film school. Since 1981 she has done several shorts and TV projects. Three of her shorts were shown at the Film Center in the summer of 1988; one of them was codirected and cowritten by the Australian fiction writer Gerard Lee, who helped Campion with the screenplay of Sweetie, and two of them were shot by Sweetie’s cinematographer, Sally Bongers. (Bongers’s work on Sweetie makes her the first woman cinematographer to have shot a 35-millimeter feature in Australia, and it’s a stunning debut.)

There are many possible ways of approaching Sweetie — through its subject, its style, its performances, and its overall transgressiveness, to name the most important — but none of them seems entirely adequate, particularly in relation to all the others. The film’s impact is relatively seamless, and to break it up into separate aspects is to ignore the way they consistently work together. Unfortunately, I lack the means to discuss all these things simultaneously, so I’ve opted for a piecemeal and sequential approach, trusting that readers will understand that the following list and its order were arrived at only as a matter of convenience. For a variety of reasons, some of which I’ll get to, I haven’t attempted to recount the movie’s plot — except for a few cases where I need to tell some of it in order to make certain points.

Subject: Although Sweetie concludes with the dedication “to my sister,” it is important to note that the film’s story is not at all autobiographical; the character of Sweetie was inspired by a real person, but a man, not a woman, and certainly not a relative of Campion’s. The director’s mother died during the shooting of Sweetie, and when she was still very ill Campion was faced with the possibility of having to turn the film over to another director in order to take care of her. Her sister flew in from England to help out, which allowed Campion to finish the film; thus the dedication.

Simply put, the subject of the film is madness — not only as it’s manifested in the title character (Genevieve Lemon), but also as it affects the three other members of her family: Kay (Karen Colston), her sister, who narrates the film; Gordon (Jon Darling), the father; and Flo (Dorothy Barry), the mother. Indeed it may be inappropriate to single out Sweetie as the mad member of the family, because Kay is pretty weird herself, and Gordon has certain traits that suggest instability, including bouts of petulance and his uncritical devotion to Sweetie. (Her given name is Dawn; Sweetie is her father’s pet name for her.) Only Flo comes across as relatively sane, from what we see of her, and she seems to have spent so much of her energy as a domestic workhorse that she has little time left to provide much family leadership; like her husband, she has a tendency of to walk away from trouble rather than face it squarely.

This is not a family that is ruled by any ordinary sense of courtesy; Sweetie does not even seem to be completely toilet trained, and when sufficiently provoked she is fully capable of barking and snapping at others like a dog. Kay and Sweetie despise one another, and make no effort to hide the fact. When Sweetie makes her first, somewhat belated appearance in the film — turning up with her boyfriend, Bob (Michael Lake), at the house shared by Kay and her boyfriend, Louis (Tom Lycos) — she gets in by breaking the glass window on the front door. Kay initially explains her presence to Louis by saying, “She’s a friend of mine. She’s a bit mental.” When Bob later points out that Sweetie is her sister, Kay retorts, “She was just born — I don’t have anything to do with her.” One of the principal dramatic conflicts in the film concerns the problem of getting Sweetie out of the house so that Kay, Louis, and Gordon can leave on a car trip to visit Flo, who has recently left Gordon in a trial separation in order to cook for cowboys on a ranch some distance away.

The ongoing tension between Sweetie and Kay has a great deal to do with sex. Sweetie and Bob arrive at a point when Kay is suffering from frigidity and she and Louis have been trying without much success to escape their “nonsex phase”; they can hear Sweetie and Bob humping away next to the spare room where Kay now sleeps alone. Sweetie, moreover, is a compulsive flirt, offering to lick Louis all over one day on the beach; when she bathes her own father, she’s quite capable of dropping the soap into the tub as an excuse for groping him. Regressive and infantile, polymorphous perverse, totally uninhibited, and brought up by Gordon to think of herself as a talented star — although her only visible talent is a “trick” that consists of climbing up on a chair and turning it over, and the only thing that keeps her from being institutionalized is Gordon’s unreasoning devotion — Sweetie by her very existence is a constant reproach and threat to Kay’s neurotic repressions, superstitions, and introspections.

From another point of view, the film’s “subject” is not so much the family as it is trees, which function as the film’s central metaphor — suggesting both unseen depths and giddy elevations, guilty secrets and dreamy aspirations, as well as family trees, planted and uprooted lives, blooming and dying, and diverse encroachments, encumberments, and entanglements. It is a metaphor that develops in both a psychological and a literary fashion, accumulating more and more resonance without ever settling on a single meaning or referent. And the film uses this metaphor more as a poetic organizing principle than as a stable element in the plot. A couple of trees do figure crucially in the story — an elderberry sapling that’s planted by Louis and secretly uprooted and hidden by Kay, and, much later on, a full-grown tree with a tree house to which Sweetie retreats — but these are only individual parts of the vast and continually expanding constellation that trees form in the film’s mental landscape.

Style — the Lynch-pin fallacy: The usual problem for critics confronted with something genuinely new is that, strapped for explanations, formulas, and ready-made labels, they reach out in desperation for reference points that will somehow bring the work safely back to earth, make it seem more familiar and less threatening: in other words, not so new. So it shouldn’t be too surprising that a certain number of lazy critics are throwing up their hands at Sweetie, even if they’re crazy about it, and concluding, in effect, “David Lynch” — simply to stave off the more difficult question of what the film is actually doing.

It’s easy enough to see what they mean if you don’t delve into the film too deeply. Campion and Lynch are both figurative painters-turned-filmmakers who favor odd camera angles, painterly compositions, and bold colors; they also share a certain poker-faced black humor and a morbid, poetic fascination with the aberrant. Campion, moreover, has acknowledged some feelings of kinship with Lynch as a filmmaker, particularly with his desire to explore mental states.

This might seem like a lot for two writer-directors to have in common — enough, at any rate, to make a strong comparison with Lynch plausible. But one also might argue that this comparison stops short of dealing with most of the things that make Campion’s style so singular. For starters, she clearly knows what she’s doing every step of the way, conceptually as well as intellectually, while Lynch is at best a crafty primitive (which is one reason why a lot of mainstream critics can feel relatively comfortable about him — he doesn’t make them feel outclassed). Campion’s compositions — which often frame upper or lower sections of bodies from unorthodox overhead angles so that they seem to jut out diagonally from the corners of the screen — are quite distinct from Lynch’s more horizontally and vertically balanced frames. Campion’s fascination with human behavior has little to do with Lynch’s nonhumanism and antihumanism — which are largely what make his kind of filmmaking possible — not to mention his campy taste for cliché, his puritanism, his Manichaeanism, his apple-pie Americanism, and his musical sense of duration.

Finally, Lynch’s films are populated with stock figures and diverse types, but not characters in any fully developed sense, while the family in Sweetie is sufficiently dense and complex to suggest the Compsons in Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury and the Tyrones in O’Neill’s Long Day’s Journey Into Night — families whose habitual behavior patterns are locked into vicious circles that stretch back over decades. Part of what makes Campion’s characters dense and complex is the way they interact as a family. Lynch’s figures, on the other hand, can’t be said to interact at all — their personal encounters are collisions, nothing more.

Identifying Campion’s style with Lynch’s, in short, makes only slightly more sense than identifying her subject with Steven Soderbergh’s in sex, lies, and videotape: both films, after all, center on the acrimonious relationship between a promiscuous sister and a sexually inhibited sister; both films tend to privilege the inhibited sister’s viewpoint and feelings, and both gradually build toward the resolution of some of her problems.

Transgressiveness: Sweetie definitely has a capacity to divide audiences. It was reportedly both booed and cheered when it premiered in Cannes last year; more recently, its box office showing in New York has not been strong, which suggests that you should probably rush off to see it as soon as possible. I’m tempted to add that people who don’t leave the Fine Arts issuing fanfares — some of whom will be as pissed off as I was after seeing Blue Steel — simply aren’t up to the emotional challenges that the movie offers. The film certainly packs a wallop whether you like it or not (by contrast, for all its pistol-packing phallus worship, Blue Steel is a soggy banana), but if you don’t agree that the best art should drive you up the wall a little, you probably aren’t going to have a very good time with it.

Blue Steel deals with mental instability as a generic cliché, using it to assign putative motivation to a standard-issue serial killer, a raving lunatic whom we’re meant to perceive as a threat but not as a human being. Sweetie takes mental instability as something real, human, volatile, consequential, and elemental, and declines to make moral judgments about it — without ever overlooking the reasons why we perceive it as a threat. Never stooping to a clinical perspective, the film nonetheless presents its characters with terrifying lucidity and human understanding; it refuses to assume that they are alien to us, and never loses sight of a comic perspective that mediates our feelings of disgust and horror. In the final analysis, normality rather than abnormality is the film’s tragicomic subject — the extremes represented by Sweetie and Kay are nothing more than the “normal” conflicts between siblings writ large — but some viewers, if they find themselves stranded on the movie’s prosey surface and back away from its poetry, may wind up feeling appalled. That will be their hard luck, because the rest of us will more likely be dazzled and exhilarated.

Part of what’s so unusual about the film is that in diving so deeply into its characters’ minds, it often bypasses the naturalistic surface details that we usually expect to get in fiction films — the sort of backup material on the characters’ lives (such as what most of them do for a living) that makes them relatively easy to synopsize. For example, the next-door neighbor of Kay and Louis is a little boy named Clayton (Adam Pataczek), a funny and likable character whom we see often and who becomes a frequent playmate of Sweetie’s. At one point we see a woman who might be Clayton’s mother in his backyard, but otherwise his parents’ presence and identities are left completely blank — not only are they absent, but in the peculiar terms posed by the film, they can’t be said to exist.

Similarly, Sweetie’s boyfriend Bob is a semicoherent layabout whom she calls her “producer,” because he “believes in” her — presumably in her future in show business. The last time we see Bob is in a luncheonette; Gordon, who has taken him there, abandons him after he nods out, drools, falls to the floor, and has some sort of fit, water from the table splattering onto his head. We never learn whether Bob is on heroin, is having an epileptic seizure, or is suffering from some other malady or some combination of the above, and the film never gives us any indication of what happens to him later; he simply disappears, undefined seizure and all. (Here, at least, the film briefly suggests a genuine parallel with Lynch, by cruelly positing Bob as a freakish comic object. But even here, Gordon’s embarrassment in dealing with Bob — attempting to loosen his clothes before he falls to the floor, and then hastily beating a retreat — is handled with a sense of psychological nuance that seems quite outside Lynch’s range.)

Thanks in part to such elisions, it is virtually impossible to synopsize Sweetie in any detail without going against its grain. To demonstrate this fact, we could try, however, with the prologue. We could say that Kay opens the film by speaking offscreen about her “sister’s tree” and how she imagined the roots of that tree crawling under her house “as if they had hidden powers,” and how that fantasy made her afraid of trees in general. We could also say that soon afterward, Kay visits a fortune teller who reads her tea leaves and tells her that the man in her future has a question mark on his face. Soon after that, in the garage adjacent to her workplace, she encounters Louis, only 55 minutes after he’s become engaged to someone else named Cheryl. She notices that Louis’s cowlick and a mole on his forehead form the shape of a question mark, announces to him that they were destined to be together, and winds up rolling with him on the garage floor, where they’re discovered by Cheryl and another woman; we next find them in a bedroom, half dressed and making love. End of prologue. (When the plot resumes, it’s after an intertitle announcing, “13 months later.”)

The problem with such a rundown isn’t only that it makes the movie sound even more bonkers than it is, and incoherent to boot; it also deprives the movie of much of its poetic and narrative logic and its sustained emotional continuity — all of which add up to beautifully fluid story telling — by extracting “plot” from a succession of shots. But given Campion’s imagination and energy, virtually each shot in the film is an event in itself, regardless of whether it advances the plot or not. Before Kay visits the fortune teller, for example, an extended tracking shot follows her as she walks down a sidewalk; then a moving shot from her point of view shows her stepping over the sidewalk cracks (which resemble tree roots); then comes a stationary setup that shows her in close-up, looking straight into the camera — an unsettling shift in narrative viewpoint that has nothing to do with the plot per se, but which prepares us for some of the splintered if lucid story telling that follows . . .

What probably matters most in the abbreviated synopses above isn’t the story but the characters and the image clusters: Kay and Louis, trees and question marks. The fact that Kay assigns a negative value to trees and a positive value to question marks raises the question of whether each figure might be only an inversion of the other. (They both seem to be connected with sex.)

The film’s progression, in any case, is one of continual discovery and revelation rather than merely description and explanation. When I saw it for the first time, at the Toronto film festival last fall, none of its numerous narrative elisions became evident to me until after the film was over. Part of its hypnotic power is its capacity to draw one into its own terms, canceling out those irrelevancies that are usually supposed to matter in movies. It’s a form of composition that recalls a phrase from Beckett (who, incidentally, was describing a painter’s work): “Total object, complete with missing parts, instead of partial object.”

Performances: Campion did her own casting for Sweetie, and none of the actors she picked had ever acted in a feature film before. If we’re lucky, we may see some of them again, but in many cases — particularly those of Genevieve Lemon as Sweetie, Tom Lycos as Louis, and Jon Darling as Gordon — their achievement is so remarkable that it’s nearly impossible to imagine them in other parts. The depth of characterization is partially present in the script, but what these actors add to their roles, in small gestures and broad strokes alike, brings them alive with a vibrancy possessed by few contemporary screen characters; their lives seem to extend beyond the borders of both the story and the screen.

Here are three random examples of indelible actor’s moments — the first two small and underplayed, the last one broad and volcanic — each of which becomes fully integrated into the film’s poetic design:

(1) Louis spends a lot of time in meditation, and at one point in the story Kay attends a meditation class herself — a gesture that proves abortive, because as she keeps telling her instructor, “I don’t feel anything — it’s not working.” Each time she makes this complaint, the instructor (Charles Abbott), with a rigidly euphoric smile, replies, “OK. Good. Just gently close the eyes.” This glib expression of mechanical validation perfectly catches the tone of such guru patter, parodies the self-containment of Louis that we notice elsewhere in the film, and serves brilliantly to articulate Kay’s own sources of frustration. A subsequent free-form interlude (beginning with a shot of the instructor in color negative, and going on to feature both trees and dancing feet) effectively elaborates upon this moment.

(2) Before Flo leaves Gordon to work at the ranch, she takes the precaution of fixing a slew of meals for him; she puts each meal on a separate plate, wraps it in cellophane, and labels it for a day of the week, then sets them all out for him on the kitchen table. Angry and hurt by her departure, Gordon walks by the table and, in a moment of pique, slightly pushes one of the plates over the edge so that it crashes to the floor. The gesture itself is a highly telling one, because it exposes in a nutshell where Sweetie’s own infantile behavior comes from; but Jon Darling’s articulation of this small gesture — which includes the pretense that the movement is almost inadvertent, half-accidental, rather than a willfully violent act — lucidly captures the degree to which Gordon is caught between the behavior of a “responsible” adult and the impulses of a spoiled child.

(3) Kay’s most prized possessions are her collection of small horse figurines, each of which she assigns a special name. When she discovers at one point that Sweetie has cut the sleeves off one of her dresses, she goes into a rage and tries to throw her out of the house; Louis intervenes, trying to calm her down while Sweetie crouches under the kitchen table. Then Sweetie goes into Kay’s room and takes her revenge by putting several of the figurines in her mouth and attempting to chew them up and swallow them. A knockdown fight between Kay and Sweetie ensues; Louis breaks it up and gently persuades Sweetie to cough up the pieces on a plate — truncated fragments that are so covered with blood that they resemble broken teeth (which, for all we know, are also included in the mess). Like much of Sweetie’s behavior in the film, the scene is downright terrifying, yet Lemon plays it in a manner that makes us fully aware of Sweetie’s fear, anguish, and desperation. She is literally trying to take possession of her sister’s domain, in the most physical way possible, at the very moment when she is being dispossessed; simply as scripted it’s a dramatically convulsive moment, but Lemon’s forlorn weeping gives it some of the grandeur of grand opera — the size of her emotions becomes every bit as awesome as the deed that they provoke.

As I cautioned earlier, the above discussion only touches on isolated aspects of Sweetie — it’s a long way from exhaustive. I’ve said nothing, for example, about the film’s unusual music, credited to Martin Armiger — a bluesy score sung by a nonreligious group of 30 singers called Cafe at the Gates of Salvation. I’ve also paid inadequate heed to how funny, buoyant, and playful much of the movie is, in spite of its dark undertones, and failed to explore how the overall vantage point of the film might be described as postfeminist. But I expect to be thinking about this movie and its characters for years to come; maybe, in time, I’ll even be able to figure out what those trees signify. As Kay points out, they’re pretty creepy.

***

Postscript: The following letter and response appeared in the May 4, 1990 issue of the Reader, under the headline “Sweetie’s Secret”. On further reflection, I think that Ms. Lortie’s analysis and argument are closer to being right than I was ready to admit at the time. — J.R.

To the editors:

J. Rosenbaum’s laudatory review of Sweetie, Jane Campion’s first feature film (March 30 issue) contained a crucial and almost offensive blindspot. He describes Sweetie as a “compulsive flirt” writing that “even when she bathes her own father, she’s quite capable of dropping the soap into the tub as an excuse for groping him.” His easy “when she bathes her own father” makes it seem as if such an act were a normal part of any father/daughter relationship. Excuse me?

Sweetie’s “madness” and pain come from somewhere, are rooted in some past events or state that Jane Campion never shows us directly. I believe that the scene Mr. Rosenbaum so superficially describes is, in fact, the biggest hint: that Sweetie is a victim of incest. The scene is important because of how it is shown to us in relation to Kay (Sweetie’s sister). Kay witnesses this bath scene (we see it through her eyes); the next cut is of Kay lying on her bed, troubled and pensive, obviously deeply affected by what she just saw. It is the first time Kay sees this act of bathing but by the familiarity between both Gordon (the father) and Sweetie (indeed, by the very fact of her bathing him) we see — as Kay does — that this has happened before. Moreover, Sweetie’s behavior while bathing her father is not simple “flirting” but confused and child-like, her fear and anxiety barely concealed by her act of “this is okay, I want to do this.”

Painting Sweetie as a victim of incest by her father would help explain some of the family’s deep dysfunction and emotional enmeshment (to the extent that these things can be explained and certainly part of the power of Campion’s film is how much she leaves unexplained). It would explain Gordon’s abnormal and blind attachment to Sweetie; Sweetie’s inability to go beyond her attachment to him; Flo’s anger at her husband’s irrational and principal attachment to their daughter; and Kay’s sick jealousy of Sweetie and insistence that something is wrong, though she cannot articulate what, exactly. Mr. Rosenbaum refers repeatedly to the importance of sex in Sweetie without expounding on the hows or whys of its role. I cannot be certain of my interpretation of Sweetie as an incest victim, though there are other indications, like the closing scene with the young, talented Sweetie almost painfully singing a love song to her father. But I am certain that it is not “normal” for a grown daughter to bathe her father and am disturbed by Mr. Rosenbaum’s characterization of Sweetie as a “flirt.” Sweetie’s “flirting” is an acting out — as are all of her antics — of deep psychological disturbances. In his review, Mr. Rosenbaum does not delve too deeply into the reasons for Sweetie’s behavior but instead seems to accept it as a simple, rootless fact. While Campion keeps us guessing as to the genesis of Sweetie’s troubles, I doubt that she intended for us to see them as unconnected from the whole dysfunction of the family. Mr. Rosenbaum states as much, which is why I am confused by his ignorance or blindness towards what are appropriate boundaries in a father/daughter relationship. He places Sweetie, by his description of the scene, in control. But what can we say of a father who “allows” his daughter to bathe him? Isn’t he (the only person in the film capable of controlling Sweetie) more responsible because he is her parent? In short, the scene is more important than Mr. Rosenbaum describes it to be and he would have done well enough to leave it alone rather than characterizing it so wrongly.

Thank you for your time.

Paola Lortie

Oak Park

Jonathan Rosenbaum replies:

I’m sorry to have offended Ms. Lortie with my perhaps too-breezy account of Sweetie bathing her father and the implications of this brief scene. I certainly didn’t mean to imply that this was “normal” behavior, even for a “compulsive flirt,” and if it sounded that way, this was an unfortunate consequence of trying to convey a lot of information in a relatively short space — and, as I suggested elsewhere in the review, trying to describe a movie that resists synopsis. Ms. Lortie’s incest theory is suggestive, but, considering the lack of further evidence in the film, by no means conclusive. Campion is clearly too sophisticated a filmmaker to be blind to psychology, but it strikes me as being part of her remarkable imagination and freedom that she isn’t necessarily bound by it either — which suggests that a character like Sweetie refuses to be definitively “explained” or accounted for by anyone or anything.