From the Chicago Reader (September 28, 1990). This is the first time I wrote at length about what is still my favorite Eastwood film; the second time was many years later, and that piece can be found here. — J.R.

WHITE HUNTER, BLACK HEART

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Clint Eastwood

Written by Peter Viertel, James Bridges, and Burt Kennedy

With Clint Eastwood, Jeff Fahey, George Dzundza, Alun Armstrong, Marisa Berenson, Timothy Spall, and Mel Martin.

I can’t say that I’ve been one of Clint Eastwood’s partisans. He was amusing as the Man With No Name — the mean, laconic hombre whose supercoolness suggested a hip Gary Cooper — in Sergio Leone’s mid-60s western trilogy (A Fistful of Dollars, For a Few Dollars More, and The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly), and fun in Coogan’s Bluff and Two Mules for Sister Sara shortly afterward. But for me the joke of this ornery, poker-faced, string-bean dude was already running thin as early as Dirty Harry (1971), a right-wing remake of High Noon that amplified Eastwood’s relation to Cooper and marked the point at which he was moving commercially into high gear. (To my mind, the gothic excesses and male hysteria of The Beguiled, made the same year — a Civil War tale in which Eastwood was seduced and unmanned by a bevy of females in a girls’ school — were much more interesting.)

Eastwood emerged from his apprenticeship with Don Siegel to direct Play Misty for Me (also 1971), the kinky misogyny of which, while undeniably quirky, was so unedifyingly unpleasant that I skipped his next several pictures, despite the enthusiasm of many colleagues for some of them (especially The Outlaw–Josey Wales and The Gauntlet). By the late 70s everyone from Orson Welles to Jean-Luc Godard — not to mention many of my smarter colleagues — was expressing admiration for Eastwood as a director, and while I could certainly see that he was a committed maverick who was making personal films, his macho sensibility and his political and aesthetic conservatism repelled me — or at least discouraged me from looking for anything deeper.

Bird made me substantially rethink my biases without actually overturning them, and two pictures starring Eastwood, both made by his production company and directed by his longtime associate Buddy Van Horn — one rather silly (The Dead Pool, a Dirty Harry thriller), the other rather good (Pink Cadillac) — were so personal and idiosyncratic that I began to warm to him further in spite of myself. His apparent distaste for both Dirty Harry and the character’s continuing popularity — awkwardly shoehorned into the plot via some terse remarks about the sickos who enjoy violence in movies — makes virtual nonsense out of The Dead Pool (as I wrote at the time, it’s the pot calling the kettle black). But at least it’s a kind of nonsense that one can feel some sympathy for — the impatience of an actor to move beyond the persona that made him famous; and his high-spirited ridicule of white supremacists in Pink Cadillac was no less bracing. Moreover, the feisty and likable heroines in both Bird and Pink Cadillac — neither of them psycho femmes fatales like the female leads in Play Misty for Me and Sudden Impact — made me reconsider dismissing Eastwood’s view of women as simply misogynist.

It seems clear that Eastwood is often at the mercy of the scripts he finds; while he obviously plays some role in shaping them, he generally isn’t the one who initiates them. Pale Rider might be better than the sub-Shane cornball pretension I thought it was when I saw it; but if it is, I would wager that this is because his direction transcends the script — not because the script in question doesn’t need transcending.

The quantum leap represented by White Hunter, Black Heart from the earlier Eastwood films I’ve seen, Bird included, is the result of three separate factors: (1) he’s working, perhaps for the first time, with a truly first-rate script; (2) he’s developed the directorial skills to get the maximum out of such a script; and (3) he’s attained a freedom as an actor that allows him to take the risk of serving both the script and his own direction rather than the predilections of his usual audience. As good as the script is, most directors I can think of would have botched it, and most male stars I can think of would have botched the lead part as well. To properly appreciate this film one has to see script, direction, and acting as three interacting and interlocking voices; two of these voices happen to belong to Eastwood, but interestingly enough, they are not the same voice — and without the intellectual ammunition provided by the script, neither one of them would have very much to say.

Peter Viertel’s 1953 roman à clef White Hunter, Black Heart may be considered a sub-Hemingway literary work, but I’ve never managed to get all the way through it. Viertel is the son of distinguished Eastern European Jews, Austrian writer and director Berthold Viertel and Polish actress and writer Salka Viertel, who settled in Hollywood in the 20s and became key figures in the intellectual emigre community there. Viertel himself became a novelist and screenwriter; among other pictures he worked on Hitchcock’s Saboteur, two Hemingway adaptations (The Sun Also Rises and The Old Man and the Sea), and three John Huston features (We Were Strangers, The African Queen, and Beat the Devil), usually in collaboration with others.

In the case of The African Queen (1951) — the preproduction of which formed the basis for White Hunter, Black Heart — he was recruited in Europe by his friend John Huston to help polish a script written in Hollywood by James Agee. Before embarking for Africa, Viertel met with Huston in the English countryside, where it soon became apparent that Huston’s only real interest in the picture was the opportunity it provided for big-game hunting — specifically the chance to shoot an elephant. It also became clear that he wanted Viertel along mainly as a hunting companion, his job as screenwriter being merely an excuse. Having purchased a lot of expensive hunting equipment and blithely charged it to producer Sam Spiegel, Huston originally promised to go hunting only after the picture was shot; but his obsession with the hunt was such that he wound up flying to Africa with Viertel ahead of the cast and crew, ostensibly to scout locations but actually to stalk elephants — which he continued to do after the others had arrived (including Katharine Hepburn and Humphrey Bogart, as well as Spiegel). Viertel, who ended up as the go-between, eventually found his friendship with Huston in a state of crisis — the sticky situation that became the main focus of the novel he published two years later.

Viertel’s novel, apart from its cachet as a behind-the-scenes look at Hollywood filmmaking in general and Huston in particular, belongs to a specific genre that might be called the critique of Hemingway from within — a kind of sportsmanlike one-upmanship whose practitioners include, among many others, James Jones, Norman Mailer, the neglected Bernard Wolfe, and even Hemingway himself (particularly if one includes The Garden of Eden, the fascinating and provocative novel that he never found the courage or wherewithal to finish). Judging from Viertel’s novel, as well as his film adaptations of The Sun Also Rises (a slick and uninteresting Hollywood reduction) and The Old Man and the Sea (an exercise in soporific piety), his response to Hemingway seems far from critical, but when faced with the crazed Hemingway-esque behavior of John Huston in Africa, he evidently began to have a few doubts.

The genre I’m referring to is an especially ambiguous one, because sometimes these authors’ quarrels with Hemingway wind up as backhanded validations. At its best, the genre is capable of yielding a good many potent insights: Wolfe’s “Dearth in the Evening” is a dazzling essay that begins as a parody-critique of Death in the Afternoon, continues as a philosophical inquiry into bullfighting, and winds up as theoretical speculation about why Hemingway committed suicide. (One of Wolfe’s strongest arguments is that despite Hemingway’s repeated attacks on the practice of endowing animals with human traits, his remarks about the nobility and tragedy of bulls in the ring — and the corresponding “comedy” of the eviscerated horses — are prime offenses in that realm.) But at its silliest — which includes much of Mailer along with Viertel — this genre seems to lust after Hemingway’s glamour while carping at some of his fine print. The problem I had and continue to have with Viertel’s novel is a more complex version of my objection to The Dead Pool, i.e., with the pot calling the kettle black. The book is so preoccupied with the male rivalry and jockeying for position of the two principals, Viertel and Huston stand-ins Pete Verrill and John Wilson, that one winds up with not much more than the image of two little boys comparing their respective penises. Perhaps if Viertel were a more lyrical artist he might have made something more luminous out of the subject (as did Nicholas Ray with his Bitter Victory), but for me the story never develops beyond its most obvious surface impression: two spoiled brats fighting to establish which of the two is more manly.

The script of White Hunter, Black Heart has been kicking around Hollywood in one version or another for quite some time. The final screenplay is signed by Viertel himself, James Bridges (the writer-director of The Paper Chase, The China Syndrome, and Urban Cowboy), and Burt Kennedy (a veteran western director) — strange bedfellows who I suspect worked on the script sequentially rather than at the same time — and Eastwood undoubtedly had some input as well. It comes across less like its sprawling source and more like a finely tuned short story; one of the best things about it, for Eastwood’s purposes, is that the Verrill/Viertel character, who narrates the novel, is here mainly reduced to a narrative device, like Thompson, the faceless reporter who treks through Citizen Kane.

To be fair, Verrill is more of a character than Thompson is — he’s not merely an observer, but an active and important participant — yet his function as a conduit between the audience and the film’s enigmatic central character is quite similar. (The casting of Jeff Fahey — a competent but rather low-key and unmemorable actor — in the part helps this strategy along.) Although the film opens with Verrill narrating as he arrives in England to meet the director of “The African Trade,” and although Verrill is around for most of the subsequent action in Africa, he exists mainly as a moral witness to the antics and behavior of Wilson. Without Wilson to give him meaning, he periodically fades into the woodwork.

In fact the only time the script falters is when Verrill becomes a little too prominent –s pecifically, when he makes a somewhat embarrassing speech about the nobility of elephants and why they shouldn’t be shot (“So majestic. . . . They’re part of the earth. . . . It makes one believe in God and the miracle of creation”) to which his companion replies, without irony, “You certainly have a way with words, Pete — no wonder you’re a writer.” The problem isn’t the sentiment (which doesn’t fully jibe with the book, in which Verrill actually shoots an elephant himself) but the mawkish way it’s expressed. Here as elsewhere, Verrill’s comments are designed to coincide with the viewer’s, but considering the doubts that are sown in other parts of the movie about Wilson’s uses of rhetoric, it’s a pity that Verrill’s weaker hyperbole — however much we may already agree with its general thrust — is given a free ride.

In all other respects, however, the film’s depiction of Africa is a model of tact, beauty, and suggestiveness; the superb musical score, credited to Lennie Niehaus and consisting almost exclusively of African music, could hardly be improved upon. And the transition between London and Africa, effected through a campy nightclub act with a gorilla and a blond ingenue, speaks volumes about the preconceived “Africa” that Wilson and his film company are bringing along with them.

Openly contemptuous of his producer (George Dzundza), abusive to his secretary, and hypocritical and patronizing to his mistress, Wilson bulldozes his way into the dual project — film production and elephant hunt — with charismatic wit, spite, and style that make his very life a nonstop performance. He’s a master of using both hectoring charm and aristocratic sarcasm to get whatever he wants, which is usually plenty, and at least half of his wisecracks — the film is quite clear about this — are expressions of contempt for women.

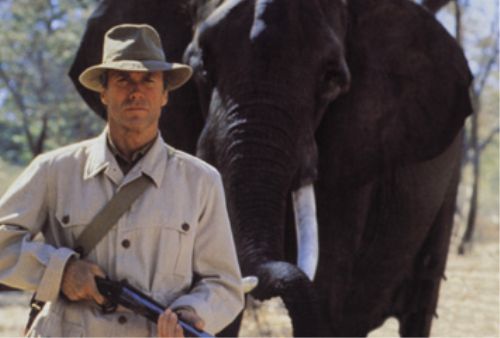

Eastwood’s performance as Wilson, which incorporates some of Huston’s gruff vocal tonalities and mannerisms, appears to be the major stumbling block for many spectators, apparently because they can’t make the jump from Eastwood’s usual lowbrow, taciturn persona to Huston’s highbrow, oratorical persona. It’s true that Huston’s favorite book was James Joyce’s Ulysses, a novel one can’t imagine Eastwood having much fun with, and it would be absurd to expect a perfect, seamless match between these two disparate and distinctive macho personalities. But in fact it’s the gap between Eastwood and Huston that makes both the performance and the film as a whole so devastating as a critical portrait.

As luck would have it, I saw White Hunter, Black Heart while I was reading Simon Callow’s recent book about Charles Laughton, one of the finest studies of acting I’ve ever read. At one point Callow quotes from Bertolt Brecht’s “Small Organum for the Theater,” and it fits Eastwood’s performance to a T: “The actor appears on stage in a double role, as Laughton and as Galileo; the showman Laughton does not disappear in the Galileo he is showing; Laughton is actually there, standing on the stage and showing us what he imagines Galileo to have been.” I’m certainly not suggesting that Eastwood set out to apply this principle systematically; he clearly arrives at it instinctively and on his own terms. (I’d even be willing to concede that he might have gotten there by default — although it’s worth pointing out that the actorly representations of Katharine Hepburn, Humphrey Bogart, and Lauren Bacall seem to be guided by similar principles of suggestive commentary; Marisa Berenson as Hepburn is especially canny.) Whatever brought him to this particular performance, it is the key to what makes White Hunter, Black Heart so remarkable. Viewers who can’t abide the notion of Eastwood as Eastwood offering a detailed running commentary on Huston — an analysis so rich and varied that it takes on not only Huston’s brand of machismo and misogyny and his self-deceiving posturings, but Hollywood bluster and colonialist arrogance in the bargain — will be deprived of the powerful polemical thrust of this movie, which drives the final nail into the coffin of the Hemingway ethic.

I’m not trying to suggest that Eastwood’s attitude toward Wilson/Huston is one of simple and unambiguous condemnation; it’s more one of detached curiosity tempered by an increasing amount of skepticism. If the character finally winds up seeming like a fool, Eastwood hasn’t made that judgment from a safe and superior distance; he’s implicating aspects of himself and his own persona along the way. If he had somehow contrived (with the use of heavy makeup, say) to make his impersonation of Huston letter-perfect (and Oscar-ready) rather than merely suggestive, most of the point of his performance would have been lost, because in the final analysis this isn’t simply a movie about Huston and what he represents. It’s a movie about Eastwood examining Huston via himself, and examining himself via Huston — a series of transactions that, thanks to all the issues broached by the script, proves to have a great deal of intellectual content as well as truth.

What emerges is not a pretty picture. The film winds up saying things about the Ugly American in terms of both Hollywood and colonialism that carry additional force and conviction because a conservative like Eastwood is voicing them (as a director, not as an actor). It tells us, among other things, that the self-styled anti-Hollywood Wilson is actually the epitome of Hollywood, that his supposedly uninhibited behavior is a form of psychic self-imprisonment (and his macho stoicism is at least in part a form of emotional and sexual cowardice), and that his self-righteousness about intellectual, moral, and sensual freedom is ultimately an excuse for tyranny and sadism. His eloquence and charm aren’t overlooked either; it’s a complicated portrait. But I don’t think anyone can accuse Eastwood of letting the character off easy.

The film’s centerpiece, set on the patio of an African hotel restaurant, involves Wilson responding with emotional violence to anti-Semitic remarks from his female companion (Mel Martin) and then with physical violence to the white hotel manager’s abuse of an African waiter. The scene is reportedly an almost verbatim account of two events that actually occurred when Huston and Viertel were in Africa, transcribed by Viertel immediately afterward, and what is remarkable about them is the highly complex and conflicted sense of moral priorities that they reveal; in one fell swoop, Wilson’s apparent hatred of racism, his virulent misogyny and sadism, his gallows humor, and his appetite for gratuitous violence are all exposed, and the viewer is left to pick up and sort out all the pieces.

The film’s perfectly articulated final scene is nothing short of astonishing. In terms of framing, pacing, cutting, mise en scène, and Eastwood’s performance — a matter of gestures, postures, facial expressions, and the delivery of one indelible word — it shows that he’s not only a much better director than Huston ever was, but potentially a great one. Dirty Harry fans longing for the old Clint are likely to be puzzled and distressed, but I’m reminded of James Agee’s reply to the fans who couldn’t forgive Charlie Chaplin for abandoning the tramp to scale the dizzying heights of Monsieur Verdoux: “Very young children fiercely object to even minor changes in a retold story. Older boys and girls are not, as a rule, respected for such extreme conservatism.”