From the Chicago Reader (January 3, 1992). A 2020 postscript to my remarks on For the Boys has been added. — J.R.

Looking at the big-time U.S. studio releases of 1991 — most of which enjoyed free supplements to their hefty advertising budgets from every branch of the media — we’d have to conclude that this was a year without enduring masterpieces. The best are intelligent entertainments, most of which faded quickly from memory. If I had to choose the ten best from this group, they’d be (in alphabetical order): Barton Fink, Beauty and the Beast, Bugsy, Defending Your Life, The Fisher King, For the Boys, Jungle Fever, Once Around, Rambling Rose, and Thelma and Louise. Equally good or even better are some new American pictures that didn’t get anything like the same national attention: Chameleon Street, City of Hope, The Deadman (only 37 minutes long, but better than most features I saw), Hangin’ With the Homeboys, A Little Stiff, My Own Private Idaho, Poison, Reunion, and Trust. The best American documentaries that come to mind are Butoh: Body at the Edge of Crisis, Inside Life Outside, Lines of Fire, Paris Is Burning, Private Conversations on the Set of Death of a Salesman, Sex, Drugs, Rock & Roll, and the videos of Sadie Benning.

But the most accomplished and effective American “moviemaking” of the year — certainly the most consequential — were two TV specials, an extended series called Operation Desert Storm and a single weekend marathon, The Anita Hill/Clarence Thomas Hearings. Like the major studio releases both of these epics benefited as well as suffered from numerous media accommodations — complete with thumbs up/thumbs down reviews — and I fear that public memory of them may be equally short.

Operation Desert Storm successfully sold the American public on the idea that thousands of innocent Iraqi lives were of little meaning or value when compared to the heady if brief excitement of this country winning back its self-confidence. If that show was a triumph of spectacle over sense, the year’s most compelling cine-roman was Hill versus Thomas, though weekend viewers only got to see the second half of the work in continuity and complete — which, judging from the subsequent opinion polls, made all the difference. For those who watched on Friday it was a kick to see a black woman show more intelligence, seriousness, and grace than anyone else in the room. For weekend and prime-time watchers, who saw only Thomas’s theatrical rebuttals, the novelistic ambiguity was drastically reduced. It was perhaps reduced even further for those who saw the bizarre split-screen version offered by one enlightened channel on Saturday afternoon, with a ball game on the left and the Senate hearings on the right. Both Operation Desert Storm and Hill/Thomas, like ball games and many movies, showed suspenseful conflicts between winners and losers, but the real drama came from the structuring absences — the behind-the-scenes machinations that put these spectacles into place. The brilliance of the mise en scene served to conceal the degree to which everyone — with the possible exception of George Bush — lost out in the process.

The strangest phenomenon this year was the almost universal critical applause given to talented filmmakers Jonathan Demme and Martin Scorsese for unabashedly sacrificing their moral intelligence for brutal box-office killings. Both of their movies — The Silence of the Lambs and Cape Fear — featured improbable villains based on grade-school versions of the devil. If such commercial also-rans as Albert Brooks, Terry Gilliam, and Francis Coppola want to win the critical respect and box-office booty bestowed on Demme and Scorsese, I’d suggest they get to work on thrillers about rapists or serial killers who devour facial parts (eyes, ears, and noses haven’t been tried yet). And to cinch approval of the New York critics they should make sure that politically correct FBI agents are assigned to track these monsters down.

The ten films on my own list of favorites for 1991 — the movies I most look forward to seeing again — are all a bit more delicate in their appeal. (For chills and suspense I’d say Curtis Hanson’s The Hand That Rocks the Cradle, opening next week, is more successful as a straight-ahead horror thriller than anything released in 1991.) Only four of my favorites appear in the lists of new American movies given above; the other six, I’m happy to say, are all films that drew substantial crowds in Chicago, though according to the usual industry wisdom they weren’t supposed to.

1. L’Atalante. Not a new film in any ordinary sense, Jean Vigo’s convulsive French masterpiece of 1934 received its first American screening in something resembling its original form only last year. I’ve revered this lyrical love story since my teens, but this beautiful restoration gave the film entirely new meaning for me. (The other restorations and rereleases of the past year, like Spartacus and Citizen Kane, at best simply reaffirmed or amplified known quantities — and in the case of Kane, overlit prints did less than full justice to the opening newsreel and projection-room sequence.) In its highly charged poetry and sensuality — its multisexual perceptions and intuitions about what it means to be alive, which partake of both the real and the magical — L’Atalante sets a standard that makes even the best films of the year seem paltry by comparison. The best that cinema can achieve nowadays, with millions of dollars at its disposal, still pales next to what Vigo accomplished with the barest of means and under the worst possible working conditions.

2. An Angel at My Table. Jane Campion’s deeply stirring three-part adaptation of Janet Frame’s autobiographical trilogy, originally made for New Zealand TV, confirmed that Campion’s earlier Sweetie was anything but a fluke — as do the three brilliant shorts Campion made before Sweetie, which have recently become available on video. (Her most recent short, After Hours — a powerful story about sexual harassment told through a striking mosaic flashback structure –should have been broadcast nationally during the Hill/Thomas hearings, but to the best of my knowledge it hasn’t even been picked up by Chicago’s unadventurous PBS affiliate, though it was shown on New York’s Channel 13 many months ago.) In her endlessly inventive direction — an act of sustained sympathy for the “disturbed” Frame’s triumphant struggle toward fulfillment as a serious writer, informed by both imagination and critical distance — Campion never takes an obvious or sentimental route, and she refuses to resort to the zanier stylistics she set in motion with Sweetie. Furthermore she has molded the performances of the three actresses who play Frame at different ages — Alexia Keogh, Karen Fergusson, and Kerry Fox — to establish uncannily subtle and complex behavioral continuities and developments, rather than obliging the viewer to take them on faith.

3. White Dog. Samuel Fuller achieved a comparable feat of continuity with the several dogs playing the title role in his tragic fable–a prescient look at American racism that took a decade to open commercially in Chicago. Since reviewing Fuller’s corrosive masterpiece, about the efforts of a trainer to deprogram a dog trained to attack blacks, I’ve been informed that the movie did open theatrically in at least a couple of American venues shortly after it was made — in Detroit at the bottom half of an action double bill, and in New York, with Spanish subtitles, at one or more Hispanic theaters. The facts that America’s greatest living filmmaker still has to live abroad in order to work, and that White Dog, his last American picture to date, was shelved for ten years without a squeak from the populace, can probably best be explained by matching stateside afflictions of aesthetic shortsightedness and muddled political correctness. Both have somehow contrived to sweep the oversize figure of Fuller under the carpet. (Though all of Fuller’s major features are reviewed in the latest edition of Leonard Maltin’s TV Movies, you won’t find his name in the index of directors — though it includes such uninspired duffers as Stanley Kramer and Sidney Pollack.) The beauty and power of White Dog stands as an authoritative rebuttal to Fuller’s lack of recognition, and it offers a searing look at how difficult it is to try to eradicate hatred from the world.

4. Ju Dou. Zhang Yimou’s feature from the People’s Republic of China — a feminist melodrama set in the 1920s, with allegorical elements related to the present — had the most ravishing color of any new picture released this year. Politically it was hot enough to suffer a commercial fate similar to White Dog‘s: it was suppressed in its own country but shown widely abroad. (I’m told that Zhang Yimou’s subsequent feature, which I haven’t yet seen, has also been suppressed.) Its subtle social analysis of the relationship between a village and the troubled family who live in a dye factory eluded most American critics, who preferred to reduce the story to the bite-size dimensions of The Postman Always Rings Twice, but it’s clear that the Chinese censors weren’t fooled: James M. Cain would be a lot less threatening to totalitarian rule than feminist rebellion against patriarchy and feudalism.

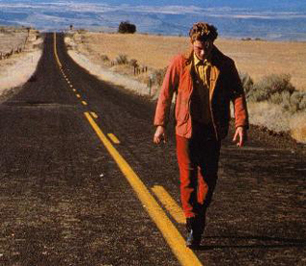

5. My Own Private Idaho. A confirmation and extension of the lyrical inventiveness of Gus Van Sant’s previous Mala Noche and Drugstore Cowboy, this beautiful and moving ballad about male hustlers — chiefly a homeless narcoleptic played with heartbreaking intensity by River Phoenix and a mayor’s son (Keanu Reeves) modeled after Shakespeare’s Prince Hal — took more chances than any other commercial American movie released this year, and most of them paid off. Plaintive road movies are by now a dime a dozen, but this one miraculously revitalized the form with a steady flow of arresting ideas and an awesome handling of image.

6. Chameleon Street. It seems inevitable that the best of all the many first features by black filmmakers released this year turned out to be the one that received the least attention. Perhaps this is because it delivered something totally unexpected from a black filmmaker in these days of ghetto expression: an authentic existentialist New Wave comedy rich in deadly ironies and ambiguities. Moreover, it follows a compulsive impostor — a dandylike rogue and antihero based on the real-life William Douglas Street — whose continuing improbable successes are spurred along by the fact that he’s black. Unlike the preachy didacticism of Boyz N the Hood, Straight Out of Brooklyn, and Up Against the Wall or the relatively ethnocentric exuberance of Jungle Fever, A Rage in Harlem, and The Five Heartbeats, Chameleon Street takes the highly unfashionable approach of addressing itself to intellectuals everywhere, without regard for ethnic affiliations or political correctness; and pace Peter Greenaway, we all know that there’s no market for an intellectual cinema in this country. Wendell B. Harris Jr., the highly gifted writer-director-star, demonstrates probably the darkest sense of what it means to be an American black since Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man and the late stories of Richard Wright, and what he does with this insight — stylistically as well as thematically — is devastating. Sadly, after winning first prize at the 1990 Sundance film festival Harris’s feature failed to find a big U.S. distributor (even after he sold the remake rights — an Eddie Murphy version is rumored to be “in development”), and Harris finally had to settle for a small independent company with few resources to peddle his singular product. His next feature is something to await with the highest expectations.

7. Europa Europa. Agnieszka Holland’s large-scale picaresque black comedy about the real-life adventures of Solomon Perel, a Jewish youth who kept himself alive throughout World War II by impersonating an Aryan, suggests in some ways a European counterpart to Chameleon Street — at least in its existential meditation on ethnic identity — although the style, the circumstances, and the historical context are all quite different. Holland’s finely honed sense of moral relativity, already fully in place in such previous features as Angry Harvest and To Kill a Priest, finds a perfect subject in this multifaceted saga about staying alive and pretending to be someone you’re not; her asssured sense of story telling and her rich cast of characters make this spellbinding.

8. Camp Thiaroye. It’s possible that I would have ranked Ousmane Sembene and Thierno Faty Sow’s masterful, novelistic Senegalese film even higher on this list if I had better understood its historical intricacies. It’s based on an incident that took place in 1944, when Senegalese troops returning from combat in Europe (as part of the French army) were sent to a transit camp, cheated out of back pay, and subjected to other indignities until they retaliated in a large-scale revolt that had horrific consequences. Leisurely paced, but with a remarkably nuanced sense of character and detail, this is the first Sembene feature to come along since the late 70s. It took three years for it to reach Chicago (it turned up at the Film Center last January), but it was certainly worth the wait. Ibrahima Sane’s performance as an intellectual Senegalese sergeant major is the most impressive in a dense gallery of full-bodied portraits.

9. Hangin’ With the Homeboys. Four friends on a night out–two blacks and two Puerto Ricans from the South Bronx — is the well-worn theme of Joseph B. Vasquez’s independent feature, and it’s a wonder how many fresh changes and insights he’s brought to this well-traveled territory. It’s a feat that’s comparable, at least in spirit, to Gus Van Sant’s reinvention of the road movie. Part of this comes from Vasquez’s graceful yet complex play with ethnic stereotypes; each of the four characters (played by Doug E. Doug, Mario Joyner, John Leguizamo, and Nestor Serrano) comes across initially as someone we’ve met before, but the beautifully orchestrated interaction between them gradually reveals that we — and they — still have a lot to discover about who they are. (Once again, the theme of impersonation comes up; one of the Puerto Ricans pretends he’s Italian.) Wonderfully acted by its entire cast, it’s full of surprises and insights, but as with Chameleon Street, distribution problems gave it only a fraction of the audience it deserved.

10. For the Boys. The word is out that this Bette Midler vehicle, which reduced me to tears of both gratitude and embarrassment, is awful: a brassy self-tribute that takes place over 50 years of USO entertainment and under 20 pounds of makeup. Directed by Mark Rydell from a script by Marshall Brickman, Neal Jimenez, and Lindy Laub, it negotiates its blockbuster aspirations with some wit and proportion, but even some people who hate it concede as much. What really seems to get their dander up is the unholy mixture of sentimentality and politics. As a friend recently put it to me, however, “Tears are the bottom line,” and I see what she means, even if this axiom doesn’t quite apply to film critics, who at least are required to make some excuses for theirs.

Conceding every last drop of this movie’s corn sweetener, I still treasure it for the following interlocking reasons (none of which have anything to do with being a Midler camp follower — I hated Beaches and barely tolerated The Rose): (1) It has enough scenic skill, period flavor, and musical smarts — including a smashing contrapuntal arrangement of “I Remember You” — to re-create the experience of seeing a patriotic Hollywood movie in the late 1940s, which was around the same time I was learning to read. (2) It has the moral intelligence to question the political meaning of that experience — especially as it relates to such post-40s phenomena of patriotic excess as Korea, the blacklist, and Vietnam, and mainly in the form of brash humanist tirades delivered by Midler to James Caan’s adept imitation of a calcified Bob Hope. (3) It contrives to combine the above two qualities in a manner that suggests how one might responsibly live with the moral and human wreckage brought about by 50 years of American patriotism and still put on a respectable flag-waving show — assuming that such a thing is possible.

But Hollywood movies like For the Boys are utopian by definition, and as a recipe for pretending to reconcile two fractured parts of my tortured American consciousness — parts that usually aren’t even on speaking terms with one another — this movie impresses me, at the very least, for having a noble purpose. Maybe you have to belong to the 40s generation in order to get the point. In his characteristic hit-or-miss Young Turk manner, Stuart Klawans in the Nation, citing For the Boys as the worst film of the year, castigates Midler for “getting up in front of a fully spangled flag and retroactively blessing American war efforts, whatever they might be.” Excuse me, but that isn’t what she does; it’s what Caan’s character does, and she and the movie both give him hell for it.

[July 9, 2020: Having just reseen this overblown film for the first time since the above was written, I now think Stuart may have been closer to being right than I was. I was moved by all of the movie’s jabs at the hypocrisies of both show-biz and patriotism, which are suggestively all but equated, but turned a blind eye on all the compromising moments and details that accepted the hypocrisies in spite of everything.]

Other movies of the year that are eminently worth seeing (excluding the American titles already listed) are The Architecture of Doom, Ay, Carmela!, Billy Bathgate, The Comedy of Money (a resurrected Dutch feature by Max Ophuls), The Double Life of Veronique, The Garden, The Interrogation, Larks on a String, Life Is Sweet, Little Man Tate, The Match Factory Girl, My Father’s Glory, Night and Day (Chantal Akerman’s latest, shown at the Chicago International Film Festival), Open Doors, Palombella Rossa, Privilege, Sangkuriang (an Indonesian feature made in 1982), See You Later (a Michael Snow short), Slacker, Strand: Under the Dark Cloth, Swan Lake–The Zone, and 1000 Pieces of Gold.

The annual F.W. Murnau award — given to the new or old film that did the most to revise my sense of film history — goes to Guy Maddin’s generally unclassifiable Archangel, a delirious, rather obscure black-and-white independent feature from Winnipeg about amnesia. Set during World War I and the Russian Revolution and largely modeled on arty studio pictures from the late 1920s and early 1930s — which basically spanned the transition from silent to sound movies — it has the most ambiguous tone of any film I can recall seeing all year, never settling comfortably into camp, pastiche, comedy, serious drama, or private reverie, but somehow contriving to hover perpetually over all of these. I still don’t know what the damn thing is, but it sure set me thinking.