From the Chicago Reader (January 10, 1992). — J.R.

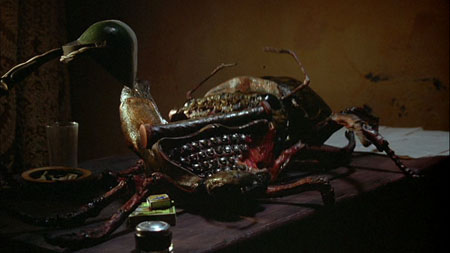

David Cronenberg’s first masterpiece since Videodrome breaks every rule in the book when it comes to adapting a literary classic — perhaps On Naked Lunch would be a more accurate title — but justifies every transgression with its artistry and sheer audacity. Adapted not only from William S. Burroughs’s free-for novel but also from several other Burroughs works (e.g., Exterminator and the introduction to Queer), it pares away all the social satire and everything that might qualify as celebration of gay sex, yielding a complex and highly subjective portrait of Burroughs himself (expertly played, under his William Lee pseudonym, by Peter Weller) as a tortured sensibility in flight from his own femininity, who proceeds zombielike through an echo chamber of projections (insects, drugs, and typewriters) and disavowals. According to the densely compacted metaphors that compose this dreamlike movie, writing equals drugs equals sex, and William Lee, as politically incorrect as Burroughs himself, repeatedly disavows his involvement in all three activities. Maybe it’s Cronenberg himself who’s doing all the disavowing; like David Lynch, his imagination seems to depend on ideological unawareness, but here, at least, it produces the most ravishing head movie since Eraserhead. In effect, it should be regarded as a “cut-up” (an interfacing of two texts) between Burroughs and Cronenberg, which means that all the original lines, characters, and meanings get somewhat scrambled and relocated in the process; the cut-up process comes from Burroughs himself, but the content that’s yielded is Burroughs seen from a highly oblique (and, one should add, heterosexual) angle. Some of the characters are from Burroughs’s biography rather than his books, and these range from acceptable caricatures of Kerouac and Ginsberg to flagrant misrepresentations of Paul and Jane Bowles. (Unabashedly postmodernist, the film casts Judy Davis as both the latter and Burroughs’s wife.) Howard Shore’s beautiful score makes superlative use of updated bebop by Ornette Coleman, creating a similar effect of displacement, and the sound and cinematography (the latter by Peter Suschitzky) are consistently gorgeous. With Ian Holm, Julian Sands, Monique Mercure, and, in a too brief appearance as the mythical Dr. Benway, Roy Scheider. (Esquire, Broadway)