From the Chicago Reader (January 24, 1992). — J.R.

HEARTS OF DARKNESS: A FILMMAKER’S APOCALYPSE

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Fax Bahr, George Hickenlooper, and Eleanor Coppola

Written by Bahr and Hickenlooper.

A little over a decade ago in an English film magazine I made a rather foolish prediction: “Perhaps by the 90s a sufficient time gap will have elapsed to allow [American] filmmakers to approach the subject of Vietnam in a more detached, balanced, and analytical manner.” Cockeyed optimist that I was, I reasoned that some historical distance would allow certain blank spots in our knowledge and understanding of Vietnam to be filled — not doused in amber and framed in gold while remaining blank spots. I took to heart Ernest Hemingway’s famous declaration in a Paris Review interview: “If a writer omits something because he does not know it then there is a hole in the story.” I reasoned that the gaping holes in our Vietnam cover story would finally reduce that protective garment to tatters and permit some light to shine through.

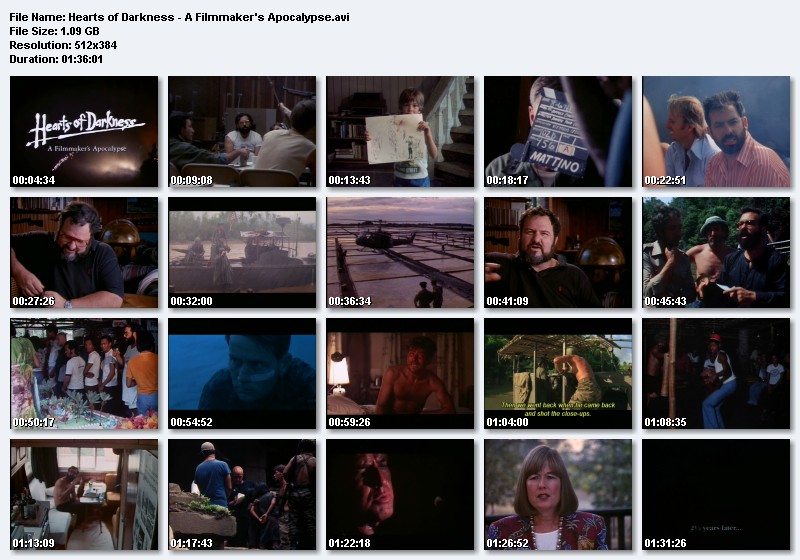

Little did I know that the holes themselves would come to be defined as points of illumination — a bit like George Bush’s “thousand points of light” — and would decorate our consciousness like Christmas trees. I offer as exhibit A Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker’s Apocalypse, a compulsively watchable, fairly entertaining, and superficially informative documentary about the making of Francis Coppola’s Apocalypse Now (1979); it premiered on cable late last year, wound up on a few critics’ ten-best lists, and is currently showing at the Fine Arts. A great deal of the film is drawn from location footage shot by Coppola’s wife Eleanor, as well as from some tape recordings she made of private conversations with her husband during the same period. This material is buttressed with recent interviews of many participants and observers — among them Francis and Eleanor Coppola; writer John Milius; actors Martin Sheen, Robert Duvall, Sam Bottoms, Larry Fishburne, and Dennis Hopper; producers Tom Sternberg and Fred Roos; production designer Dean Tavoularis; and George Lucas, who was originally set to direct the picture around 1969, before the project was shelved for lack of interest from the major studios.

Like much of Coppola’s best work — The Conversation, the Godfather trilogy — Apocalypse Now teeters on the edge of greatness, and perhaps it wouldn’t teeter at all if greatness weren’t so palpably what it was lusting after. To my mind it functions best as a series of superbly realized set pieces bracketed by a certain amount of pretentious guff, some of which might be traced back to Joseph Conrad’s novella Heart of Darkness, the movie’s point of departure. (“Is anything,” asked critic F.R. Leavis, “added to the oppressive mysteriousness of the Congo by such sentences as: ‘It was the stillness of an implacable force brooding over an inscrutable intention — ‘?”) But much of the guff, I’d wager, stems from the fact that Coppola never quite worked out what he wanted to say, a fact he often acknowledged at the time and for which there’s plenty of evidence in Hearts of Darkness. Indeed, Coppola’s continuing doubt and verbal self-laceration — at one point he calls the film “The Idiodyssey” — is a major element of the saga being celebrated here: the Passion of the Artist writ large, made to seem far more important than the mere suffering and deaths of a few hundred thousand nameless and faceless peasants (and American soldiers) across the South China Sea.

My point is that this documentary only compounds and intensifies a refusal to deal with Vietnam that existed in embryo even in Coppola’s film. The only chance Apocalypse Now had to succeed commercially was if it pleased everyone — hawks, doves, and everybody in between. Somehow it achieved that, not merely confirming everyone’s prejudices about the war simultaneously but also convincing members of each faction that it was speaking only to them. At the time journalist Deirdre English compared Apocalypse Now to the unabashedly racist The Deer Hunter, pointing out that each film “takes a fabricated act of Vietnamese terror” — the ultrasadistic Russian roulette game of The Deer Hunter, the hacking off of inoculated children’s arms (recounted in a climactic monologue by Marlon Brando) in Apocalypse — “and elevates it to become the central metaphor of the war.” Both fabrications undoubtedly grew out of tall tales told by returning American soldiers — I assume they’re fabrications because I’ve yet to see any documentary evidence of either — and they play a central ideological role in both films by furnishing a myth and metaphor to plug up the gaping hole in our understanding of what that war and that country were all about.

The opening lines of Hearts of Darkness, spoken by Francis Coppola at the 1979 Cannes film festival, are characteristic of the overall thrust of the documentary and of the rhetoric surrounding Apocalypse Now from its inception: “My film is not a movie. My film is not about Vietnam. It is Vietnam. It’s what it was really like — it was crazy. And the way we made it was very much like the way the Americans were in Vietnam. We were in the jungle, there were too many of us, we had access to too much money, too much equipment, and little by little we went insane.”

Coppola’s movie is a nice late-70s liberal statement about U.S. involvement in Vietnam and the excess it entailed — and I don’t intend “nice” or “late-70s liberal” to be condescending. For all its failings and shortcomings, Apocalypse Now was probably the best big-budget, big-statement American movie about the Vietnam war that we had in the 70s, and it’s questionable whether we’ve seen much improvement in this subgenre since. Platoon clearly is more authentic, and Full Metal Jacket at its best may conjure up more profound ideas about warfare, but neither film comes close to the total experience of spaced-out insanity and sensory overload that Coppola’s Cannes statement suggests and that his movie amply furnishes.

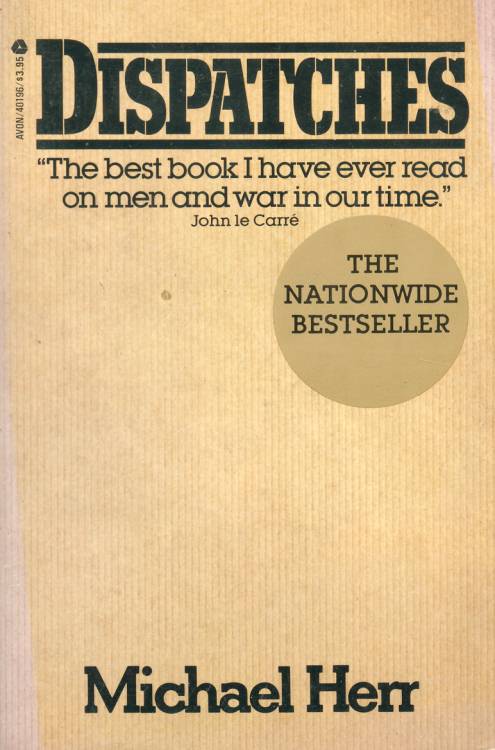

But consider what Coppola actually says: his movie is Vietnam, and by Vietnam he means “us,” not “them”; Americans, not Vietnamese. Milius put together his hawkish script out of his own imagination and tales told him by returning soldiers; he himself had no firsthand experience. Coppola had no such experience either, though he viewed U.S. involvement more skeptically. He shot the entire film in the Philippines, selected for its reputed topographical similarity to Vietnam. Only after all the footage was shot did he hire Michael Herr — the author of a first-rate book of reportage about Americans fighting in Vietnam, Dispatches — to write the film’s very effective offscreen commentary, delivered by the hero, Willard (Sheen).

Curiously, though Herr is the only creative member of the Apocalypse Now team who had firsthand knowledge of Vietnam, he isn’t interviewed or even mentioned in Hearts of Darkness. Of course Herr’s view of the war is considerably to the left of Milius’s “Conan the Barbarian” outlook. (Usually when we see Milius in this film, he’s chortling with enjoyment over his favorite instances of macho piggishness, including a favorable humorous comparison of Coppola with Hitler and himself with Gerd von Rundstedt.) Political views are not supposed to matter, however, because the facts of the war are seen as piffling next to the glorious spectacle of an American director shooting a movie in Southeast Asia. As a press release puts it, “Hearts of Darkness is an examination of Francis Coppola — a director who, at the height of his political and creative powers, placed himself, his family and his crew in a set of dangerous circumstances to discover the truths in Conrad’s story and inside himself.” Or as his wife puts it at one point, “He’d gone to the threshold of his sanity . . . or something.”

Whatever that “something” is, Vietnam isn’t within light-years of it, though it’s supposed to be the subject of the film — sort of. When Eleanor Coppola arrives in the Philippines with her three children in March 1976, she approvingly quotes her daughter’s remark: “It looks like the Disneyland jungle tour.” In the first year, deals are made with Ferdinand Marcos for a fleet of helicopters (some of them later called away in the middle of a take to fight a civil war in the south), 600 or so natives are hired at a dollar a day to build a temple set, typhoons and monsoons destroy the sets, the lead actor is replaced (Sheen for Harvey Keitel) after a week’s shooting, and Sheen’s major heart attack causes further delays. More than a year after her arrival, Eleanor Coppola films a local Philippine ritual that involves drinking, dancing, and the slaughter of pigs and chickens; profoundly moved, she drags her husband to the next ceremony, the slaughter of a carabao. The carabao is then eaten at a festival, and as a gesture of respect the mayor gives Francis Coppola the “best part,” the heart. Much later, when Coppola is shooting the final scene of Apocalypse Now, he shows the sacrificial killing of a carabao at the same time that Willard emerges from the primordial slime of the river to keep his date with destiny and murder Kurtz (Brando), the mad officer he’s been ordered to “terminate with extreme prejudice.”

What, you may ask, does any of this have to do with Vietnam? Of course the Philippines and Vietnam are both in Southeast Asia. But let’s suppose that North Vietnam had invaded the United States in the midst of a civil war. How would we feel if a Vietnamese filmmaker proceeded to Mexico to make a film about our war and wound up shooting a bullfight he happened to visit as a potent example of the activities of typical U.S. savages? And what if he then declared to the press, “My film is not about the United States. It is the United States. It’s what it was really like . . . it was crazy”?

“What it was really like” means, of course, what it was like for Americans in Vietnam — Herr’s subject in Dispatches — not what it was like for Vietnamese. And the main poetic insight of Apocalypse Now — which borrows more than just a page or two from Herr — is that, for Americans at least, Vietnam was just like a movie. In Hearts of Darkness Coppola remarks at one point, “A film director is one of the last dictatorial posts left in a world getting more and more democratic.” Clearly Coppola is likening himself to Kurtz, and similar comments crop up frequently in the documentary — as well they should, because above all else Apocalypse Now is a movie about being a movie director. The key sequence, the one everyone remembers, is Lieutenant Colonel Kilgore (Duvall) of the Ninth Air Cavalry attacking a Vietcong beachhead with Wagner blaring from the helicopters and soldiers surfing ecstatically behind the boats. (The character of Kilgore, modeled mainly on George C. Scott’s General Buck Turgidson in Dr. Strangelove, offers a comic preview of Kurtz.) We don’t need Hearts of Darkness to tell us that Kilgore’s “achievement” in this attack parallels Coppola’s achievement in setting up and executing the sequence.

To my mind, Willard functions best as first-person narrator and observer, and Kurtz functions best as his and our narrative destination (we encounter him only toward the end of the story, as we do in the Conrad novella). As characters they’re both pompous, boring macho types who seem to spend much of their time shadowboxing, quoting T.S. Eliot, or sucking on pieces of exotic fruit. (Another inspiration for Apocalypse Now may be Werner Herzog’s Aguirre: The Wrath of God, which links the fanaticism of a mad conquistador with that of the film director. But in Herzog’s film we don’t have to wait for the madman to make a grand entrance; he’s there and raving from the beginning.) The true meaning of Conrad’s story comes from what the narrator encounters on his trip down the river en route to Kurtz, and the same could be said for Coppola’s movie; these encounters are like clues to a mystery, but they’re much more suggestive and interesting when they remain clues, like the encounter with Kilgore.

It’s entirely to the credit of Hearts of Darkness that it traces Apocalypse Now back to Orson Welles’s adaptations of Conrad’s novella. Welles’s first half-hour adaptation for radio, with Ray Collins as Marlow and himself as Kurtz, aired on November 6, 1938, exactly one week after his famous War of the Worlds broadcast. In 1939 Welles developed an ambitious screenplay (never produced) that updated the story to make it reflect the rise of totalitarianism in western Europe — as well as colonialist ventures in the Belgian Congo and elsewhere in Africa — and that was constructed around an extremely daring use of the first-person camera, which took the place of Marlow. Welles’s second (and much better) radio adaptation, with Welles playing both Marlow and Kurtz, derived some of its ideas from the screenplay and was broadcast on March 13, 1945. The documentary cites only the first two adaptations and plays several excerpts from Welles’s radio narration, but unless my ears were playing tricks on me, these snippets come from both radio shows, not just the first.

The Welles connection is worth bearing in mind, in any case, because Apocalypse Now reeks of his influence: not only the portentous offscreen narration, first-person camera angles, and juicy larger-than-life character acting, but much of the chiaroscuro and other lighting effects of Vittorio Storaro’s cinematography. Even the opening shot — a close-up of Willard’s face shown upside down — seems a direct steal of the opening shots from two Welles films, Othello and The Trial. It’s also worth pointing out that if Welles’s screenplay had been filmed, it would almost certainly have had a much more pointed contemporary relevance than Coppola’s version of the story.

It’s also to the credit of Hearts of Darkness that in most of the clips from Apocalypse Now the original ‘Scope format is preserved rather than cut down to the usual video-screen ratio. Moreover, many of the participants interviewed in the film show a sophisticated awareness of the ambiguity of their enterprise. (We’re told a lot about the massive drug consumption; Frederic Forrest remarks at one point, “We felt like we really weren’t there,” and Sam Bottoms admits to using pot, LSD, speed, and alcohol between as well as during various takes. Indeed, the communal high may have been the crew and cast’s closest spiritual link to American soldiers in Vietnam, and this registers all the way through the picture.)

Missing from this production story are the scenes shot with Harvey Keitel as Willard, as well as the voice tracks of the heated script conferences between Coppola and Brando, some of which we briefly see. (We do, however, see Brando blow a couple of takes, in one case by announcing he’s just swallowed a bug.) But the biggest absence in Hearts of Darkness is not Vietnam itself but the shadow of any awareness that it’s missing. Like Willard and Coppola, we’re still journeying into ourselves — and still coming up with the same old nonanswers. In effect we’ve been triumphantly brought to the same level of understanding experienced by Coppola’s daughter when she observed: “It looks like the Disneyland jungle tour.”