From the Chicago Reader (September 11, 1992). — J.R.

SNEAKERS

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Phil Alden Robinson

Written by Robinson, Lawrence Lasker, and Walter F. Parkes

With Robert Redford, Dan Aykroyd, Ben Kingsley, Mary McDonnell, River Phoenix, Sidney Poitier, David Strathairn, Timothy Busfield, George Hearn, Eddie Jones, and Stephen Tobolowsky.

Although Sneakers has plenty of artful craft, the principal pleasure of Phil Alden Robinson’s new feature has less to do with art than it does with old-fashioned entertainment. Robinson, you may recall, wrote and directed In the Mood (1987) and the much more successful and better known Field of Dreams (1989), two movies whose basic appeal was founded in nostalgia. Though everything after the prologue and credits in Sneakers is set in the present, the movie reminds us of what movie entertainment used to be about, especially during the 50s and 60s, before inflated ideas about art and significance took over. (I suspect that many of the movie’s high-tech details come from producers and cowriters Walter F. Parkes and Lawrence Lasker, who together wrote the script of WarGames.)

Sneakers can be described in many ways: as a caper movie, a lightweight thriller, a high-tech fairy tale, a boys’ adventure, or a Hitchcockian jaunt dating back to the period before Hitchcock was regarded as a serious metaphysical artist — that is, either before he left England for Hollywood or up to the time he made North by Northwest, but in any case before the weighty French interpretations of his thrillers became coin of the realm. (There was actually a time, in certain respectable Anglo American circles, when Hitchcock was considered closer to Agatha Christie than to Nietzsche and Kafka.) Sneakers is not as good as Hitchcock at his best, though it certainly works as well with audiences judging by the two previews I attended.

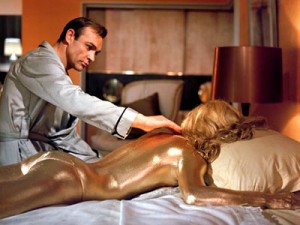

It’s interesting to consider why we associate well-crafted, doggedly unserious entertainment of this kind with the past. In the same year that Hitchcock’s The Birds was released (1963) to a mixture of critical catcalls and respectful murmurs about Greek tragedy, Pauline Kael was declaring Charade “a charming confectionary trifle,” the best American film of the year. And though her defense of unpretentious “fun” over self-conscious “art” has had strong and lasting effects on American movie tastes, it’s The Birds and not Charade — and similarly The Godfather, The Deer Hunter, and E.T. rather than Goldfinger, Bananas, and Car Wash — that has had the longer shelf life and prompted the most critical literature over the past three decades.

Part of what’s delightful about Sneakers is that one can’t imagine it courting a critical literature of any kind. Robinson shows us at the outset just how frivolous it is: the opening credits emerge from nonsensical anagrams — “Universal Pictures,” for example, is “a turnip cures Elvis” unscrambled, and “Robert Redford” proves to be “fort red border” in disguise. Eventually this technique is thematically justified by a decoding session with a Scrabble set in the middle of the picture; but by the time we get to this sequence it’s already been firmly established that giggles, not deep reflection, are the desired response to most of the movie. Even if one takes the film’s liberal biases seriously, it soon becomes apparent that the “code” for taking something seriously here is to treat it like a lark.

Redford plays Martin, a former college radical who amused himself during the 60s by transferring funds via computer from the Republican Party to the Black Panthers. (Election-year gags are plentiful.) Today he heads a high-tech team of security and surveillance specialists — the “sneakers” of the title — who hire themselves out to banks and other organizations to test their security systems by penetrating them. The four other members are Crease (Sidney Poitier), a former CIA agent with a temper; Carl (River Phoenix), a horny teenage computer whiz; Mother (Dan Aykroyd), a gadget man with paranoid conspiracy theories; and Whistler (David Strathairn), a blind audio expert and “phone phreak” with spiritual inclinations (though he reads Playboy in Braille). As Martin’s former girlfriend Liz (Mary McDonnell) points out, they’re basically a boys’ club, and when she finally gets enlisted in a project she automatically becomes den mother, landlady, and Mata Hari combined.

At times the team suggests Snow White and the seven dwarfs, and Robinson foregrounds this fairy-tale aspect in several ways. At matching junctures in the plot, for instance, each of the five men declares a “secret” wish about what he wants to be paid for his services. At other times the “sneakers” recall the symbiotic collectives of misfits in such science fiction novels as Olaf Stapledon‘s Odd John and Theodore Sturgeon’s More Than Human, though the film lacks the artistic and moral issues we associate with these works. Two agents reportedly working for the government (Timothy Busfield and Eddie Jones, who resembles J. Edgar Hoover) force the team to participate in a covert operation that leads to the discovery of a little black box that apparently cracks all existing codes. (The notion that information is power, central to the movie’s premise, is also vital to its narrative method: the film adeptly keeps the audience preoccupied with certain matters and unconcerned with others.)

One way this picture distinguishes itself from “serious” Hitchcock is by completely avoiding moral issues and ambiguities. We see the cold war seemingly reanimated, the frequent and guilt-free use of surveillance, and Liz used as a sexual decoy, but none of this is made to seem even the slightest bit questionable or disturbing; all of it is simply fun, a means of turning the wheels of the plot. In keeping with the movie’s old-fashioned values, the main villain, Cosmo (Ben Kingsley), who was Martin’s friend and coconspirator in 1969, is made to seem vaguely gay in more or less the same way a gunsel in North by Northwest was.

Compulsive attention to narrative continuity has a lot to do with the fact that such issues are forgotten. Keeping the spectator busy anticipating what comes next is an excellent way of ruling out moral and logistical considerations. At one point, for example, Martin has to make a call to the National Security Agency, the government office that has employed him and his team. To try to prevent the call being traced, Whistler bounces it through eight relay stations around the world and off two satellites; meanwhile Mother sets up a gadget registering “voice stress” to help determine if the person at the other end is lying. Whistler then proceeds to trace the tracing on the call while it’s being made, while Mother ticks off whether the people on the other end are being truthful or not. With this much information (and potential for suspense) afforded through crosscutting, we barely have the time or wherewithal while the call is in progress to judge its verisimilitude and informational value.

Part of the pleasure afforded by such a sequence comes from the careful exposition of intricate teamwork, combined with an adroit attention to the personalities involved; another part has to do with suspense mechanisms themselves, and the control over information flow they give the filmmaker. Perhaps best of all about this sequence, however, is the feeling of complicity with the “sneakers,” whatever they happen to be doing; if they operate like the fingers of one hand, we’re happy to provide the thumb whenever necessary.