From the Chicago Reader (October 8 , 1993). — J.R.

Let’s start with the bad news, which also happens to be the good news. With the erosion of state funding virtually everywhere and the concomitant streamlining of many film festivals toward certifiable hits — basically what an audience already knows, or worse, what it thinks it knows — there isn’t a great deal of difference anymore between the lineups of most large international festivals, including Cannes, Berlin, Venice, Toronto, and even Chicago. By and large, the critics at Toronto last month, myself included, who thought it was an unusually good festival were those who hadn’t made it to the previous three big festivals.

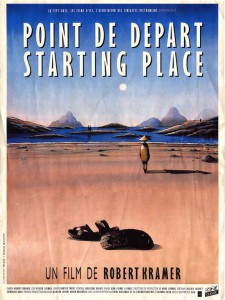

Some films don’t make every list, of course. Luc Moullet, probably the most gifted comic filmmaker working in France, almost never seems to attract international interest, and I was disappointed to discover that his delightful Parpaillon, which I saw in Rotterdam, was passed over by Toronto, Chicago, and New York. The same goes for Robert Kramer’s Starting Place, which I saw in Locarno — a beautifully edited and moving personal documentary about contemporary Vietnam. I’m also sorry that Hou Hsiao-hsien’s The Puppetmaster and an intriguing American independent effort called Suture, both of which I saw in Toronto, are missing from the Chicago roster.

Yet generally speaking, as far as important films are concerned, the differences between the big festivals are mainly circumstantial. This month’s New York festival is showing the world premiere of It’s All True, a documentary about Orson Welles’s unfinished Brazilian film, but the same feature opens at the Music Box late this month. However, the New York festival — which unlike Toronto and Chicago never accepts anything sight unseen — isn’t showing either Chantal Akerman’s From the East or Jean-Luc Godard’s Hélas pour moi, both important (albeit difficult) films that made the Toronto and Chicago lineups.

This leads me to the good news: of the 100 features that the 29th Chicago International Film Festival is showing, the 15 I’ve seen are all pretty much worth seeing, and I’d certainly like to see about eight more based on what I know or have heard about them. This is a healthy number of seeable movies for any festival, and for this accomplishment alone the Chicago festival should be applauded. All the screenings, moreover, will be held at Pipers Alley and, the Music Box, an arrangement that worked very well last year.

Three of the films I’ve already seen — Robert Altman’s Short Cuts, Jane Campion’s The Piano, and Mike Leigh’s Naked — are scheduled to open here commercially, and three more are older features by Jerry Schatzberg that have already had commercial runs. Most of the nine others are highly unlikely to be distributed commercially; in roughly descending order of preference these are Jean-Luc Godard’s three-year-old Nouvelle vague, Chantal Akerman’s From the East, Godard’s brand-new Hélas pour moi, Tian Zhuangzhuang’s The Blue Kite, Manoel de Oliveira’s The Day of Despair, Ray Muller’s three-hour The Wonderful, Horrible Life of Leni Riefenstahl, Dusan Makavejev’s Gorilla Bathes at Noon, Clara Law’s Autumn Moon, and Chen Kuo-fu’s Treasure Island. The films I haven’t seen but would most like to see are, in no particular order, Chen Kaige’s Farewell My Concubine, Krzysztof Kieslowski’s Three Colors: Blue (scheduled for commercial release, along with Farewell, which by then will have been cut by Miramax — if it hasn’t been already), Gurinder Chadha’s Bhaji on the Beach, Tsai Ming-liang’s Rebels of the Neon God, Ildiko Szabo’s Child Murders, Atom Egoyan’s Calendar, Serge Toublana and Michel Pascal’s Francois Truffaut, Stolen Portraits, and Agnes Varda’s The Young Girls Turn 25.

This still leaves 77 features, 16 programs of shorts, and various other festival events unaccounted for, which leads me to wonder once again why the festival would want to unload such an unwieldy number of films at a time when my colleagues and I–not to mention the general public — are least likely to be able to see them. Two of these films, The Man by the Shore and White Marriage, have already appeared in Chicago at the Film Center (the first under the title The Man at the Quay, with the director in attendance, the second as part of the Polish film festival), which can undoubtedly be ascribed to the sort of absentmindedness that comes from the pressure of the overload. But why the overload? Counting all the repeat screenings and two very welcome entries that were booked after the festival schedule went to press (Godard’s Hélas pour moi and his earlier Nouvelle vague, to be shown at 7 and 9 PM respectively at Pipers Alley on Wednesday, October 20), the festival is scheduling 228 programs over a 17-day period (a longer stretch of time than any other festival in the world, as far as I know). Given the great quantity of dross that’s bound to appear along with the gold, would anyone be seriously culturally deprived if next year the festival narrowed its sights to half as many items?

I realize that a lot of disparate interests need to be served by any big-city festival — including the desire of some wealthy people to be in the same room as Tom Cruise for $200 each (which does, however, ease the festival’s budgetary problems) and the understandable curiosity some people have to see any movies at all from such places as Armenia, Burundi, Estonia, Iceland, the Ivory Coast, Kazakhstan, and Niger. The fact remains that Luis Bunuel’s neglected The Young One — reviewed in this section of the Reader, and showing this week at Facets Multimedia — is a better movie than almost any of the festival selections I’m aware of. It seems to me that any festival looking for quality should dip into the wealth of past cinema and bring to light important work that wasn’t properly seen or absorbed in its own time. Sad to say, few big festivals have this on their agendas, and the commitment most of them have to film history seems to shrink with every passing year.

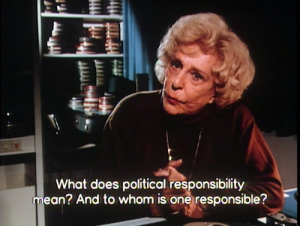

The late critic Carlos Clarens used to fantasize about what would happen if the Hollywood studios failed to release a single new movie in a given year. As he put it, this would create a utopian situation, because the studios would then be forced to rerelease the gems from their bountiful libraries of older films, and we’d have a better year of movies than we could otherwise hope for. The absence of any substantial retrospective at the Chicago festival this year only points to the degree to which the movie business as a whole is mired in the relatively impoverished present. It is offering an illustrated lecture, “Origins of Film,” by the French Film Museum’s Glen Myrent, and three films each by Jerry Schatzberg and Claude Sautet (both of whom will be at the festival) as a tribute to the venerable and valuable French film monthly Positif — but that’s only 7 programs in a festival with 221 devoted to films made since 1990, one of the most dubious stretches in the history of cinema. But I suppose this simply reflects the skewed priorities of our current culture (i.e., market).

In the reviews that follow, films that reviewers especially liked are preceded by a check mark. I wish you luck.

The festival runs from Friday, October 8, through Sunday, October 24. Screenings are at the Pipers Alley Theatre, 1608 N. Wells, and the Music Box, 3733 N. Southport. Tickets can be purchased at the festival store at Pipers Alley and at the theater box offices an hour before show time; they’re also available by phone (for a service charge) at 559-1212 and 644-3456. General admission to most programs is $7; $6 for students and seniors; $5 for Cinema/Chicago members. Shows before 6 PM at both theaters are $5, $4 for students, seniors, and Cinema/Chicago members. Festival passes are also available. For more information call 644-3456 (644-FILM).