From the Chicago Reader (November 25, 1994). — J.R.

* MARY SHELLEY’S FRANKENSTEIN

(Has redeeming facet)

Directed by Kenneth Branagh

Written by Steph Lady and Frank Darabont

With Kenneth Branagh, Robert De Niro, Helena Bonham Carter, Tom Hulce, Aidan Quinn, Ian Holm, Richard Briers, and John Cleese.

* JUNIOR

(Has redeeming facet)

Directed by Ivan Reitman

Written by Kevin Wade and Chris Conrad

With Arnold Schwarzenegger, Danny DeVito, Emma Thompson, Frank Langella, Pamela Reed, and Judy Collins.

Through a perverse coincidence, Kenneth Branagh and his wife, Emma Thompson worked simultaneously, on separate continents, on two lousy features about men usurping the reproductive roles of women. In many respects, these movies are radically different: Branagh’s pre-Thanksgiving turkey, misleadingly titled Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, is the umpteenth screen adaptation of what is arguably one of the greatest feminist novels and perhaps the first serious example of science fiction. Thompson’s movie, a Thanksgiving release, is a Ivan Rietman “family-values” fantasy-comedy about Arnold Schwarzenegger becoming pregnant — a high-concept obscenity that seems inspired by the combined successes of Twins (which also starred Schwarzenegger and Danny DeVito) and Tootsie (which also contrived to show how men make better women than women, a project also taken up by The Crying Game). Branagh’s film has (deservedly) done poorly at the box office, and if industry forecasts and early responses are to be trusted, Reitman’s movie will (undeservedly) be a huge success. But the root impulses of both pictures still have a lot in common.

One positive offshoot of the failure of Branagh’s film is that it finally allows us to place his talent in perspective. After positioning himself, with the encouragement of some reviewers, as the next Laurence Olivier or the next Orson Welles, Branagh has directed a movie that shows less distinction and imagination than the disparate Frankenstein remakes and spin-offs of James Whale, Rowland V. Lee, Roy William Neill, Terence Fisher, Jack Smight, Roger Corman, and perhaps even Charles Barton (in Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein) and Paul Morrissey (who climaxed his 1974 3-D Flesh for Frankenstein with a memorable gloss on Last Tango in Paris: “You can’t say that you know life, Otto, until you’ve fucked death in the gallbladder.”)

It’s sad that media critics see fidelity to Anne Rice’s novel in a movie adaptation as a more pressing issue than fidelity to Mary Shelley’s novel, though perhaps it’s not surprising given that a faithful adaptation of Shelley’s novel, with its extended philosophical and political reflections, would be commercially unthinkable. Yet even if one concentrates only on the spirit of the novel, one can argue that the Branagh film, with its labored script by Steph Lady and Frank Darabont, only compounds the many distortions found in most other adaptations.

To understand the original it helps to bear in mind a few facts about Mary Shelley, born Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin in England in 1797. Her mother died shortly after giving birth to her, following a severe hemorrhage. In 1814 Mary ran off to the continent with the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, and in 1815 bore a daughter who soon died. In 1816, she married Shelley, bore a son, William, who lived, and started writing her first novel, Frankenstein, which she completed before she was 20 and published anonymously before she was 21. All these experiences are in the novel.

The confusion that has always existed in the public mind between Victor Frankenstein, the book’s principal narrator, and the monster he creates — who narrates six chapters of his own — is not so much a misreading of the book as an unconscious absorption of one of the book’s central and probably conscious ambiguities, which makes these characters doppelgangers. The book’s full title, Frankenstein: or, The Modern Prometheus, helps foster this confusion, for in many respects the monster is the book’s tragic hero and Frankenstein its villain. Shelley’s passionate identification with both characters can be intuited from an entry she wrote in her journal about a nightmare she had the month after her first child died: “Dream that my little baby came to life again; that it had only been cold, and that we rubbed it before the fire and it had lived.” As critic Brian W. Aldiss aptly notes after quoting this entry, “From its very inception, the monster was a part of her.”

In this movie, however, Victor Frankenstein is squarely the hero, perhaps because Branagh himself who’s playing him, and the monster, played by Robert De Niro, is relegated to the wings as what might be called tragic relief. The only time the two characters are allowed to function as true doubles is shortly after the monster’s creation, when a bare-chested Branagh is trying to prop up a nude De Niro, and both keep slipping and thrashing about in the amniotic fluid Frankenstein has procured from pregnant women for his experiments; the fluid has splashed out of the vat that nurtured the monster and covers the floor of the lab like some primordial muck. It’s worth stressing that this messy scene, which comes across like a bout of homoerotic mud-wrestling, does not occur in the novel.

Perhaps the most telling distortion of the book concerns Frankenstein’s creation of a mate for the monster, carried out at the monster’s request to put an end to his abject isolation. In the novel Frankenstein has nearly completed the female creature when the original creature turns up, and Frankenstein, already conflicted about what he has done, viciously tears the “bride” to pieces: “The wretch saw me destroy the creature on whose future existence he depended for happiness, and, with a howl of devilish despair and revenge, withdrew.” Soon afterward, the monster returns to promise Frankenstein, “I shall be with you on your wedding-night,” and much later, true to his word, he kills Elizabeth after she and Frankenstein are married, a scene the novel pointedly keeps offstage.

The movie offers a grotesque reversal of all this: Frankenstein decides to get married before creating a mate for the monster, and after the monster yanks out Elizabeth’s heart (an added touch) on their wedding night, Frankenstein uses her corpse as the raw material for his second creation, a creature meant only for him — in effect, a life-size Elizabeth doll. (Helena Bonham Carter gamely plays both Elizabeth and her facsimile.) When this female creature comes to life Frankenstein and the monster make separate appeals to her. She can’t decide between them and eventually responds by setting herself on fire, as if to say, “A plague on both your houses, and me too, guys.”

In short, Mary Shelley allowed the monster to carry out an equitable revenge, but the screenwriters make him simply throw a tantrum. Furthermore they turn both character’s prospective mates into one single, all-purpose beanbag, who conveniently and graciously commits suicide, clearing the field for those mud-wrestling jocks.

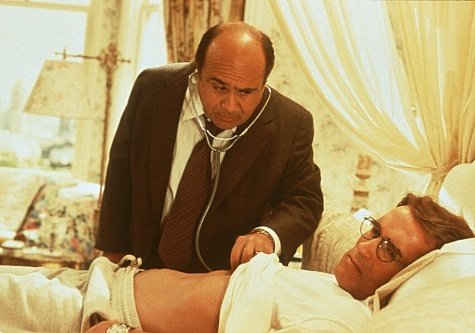

Insofar as the novel Frankenstein could be called the mother of modern science fiction, Junior could be seen as one of its countless bastard offspring, with Danny DeVito in the Frankenstein part and pregnant Schwarzenegger as the monster he creates in his lab. When it comes to the women, the story’s rather different — no revenge is involved, and DeVito’s prospective mate, who’s also pregnant (but not by DeVito), is his former wife, played by Pamela Reed, while Schwarzenegger’s prospective mate, played by Emma Thompson, is a cryogenics specialist who unwittingly provides the egg for Schwarzenegger’s baby. But the spirit of Branagh, if not Mary Shelley, hangs over the film: for all the “family values” props, including various sops to the women in the audience, this is basically another love story/grudge match between a couple of guys; they even share the same house for the better part of the movie.

People who find this good-natured comedy amusing are apt to describe it as “cute,” though if Rietman had contrived to make a jaunty heart-warmer about Julia Roberts sprouting a penis, I doubt that the same adjective would apply, even with the best will in the world. The fact remains that patriarchal comedy is the operative mode here, and every gesture made to alter that is strictly salad dressing.

Even the film’s title tells you as much, though the movie’s dialogue works overtime trying to persuade you otherwise. “Junior” is the name assigned by Thompson’s character to her egg, which DeVito swipes to implant inside Schwarzenegger — after Schwarzenegger fertilizes it with his sperm — to test a fertility drug the two men have been developing. Thompson calls her egg “Junior,” she explains at one point, because she doesn’t know whether it’s male or female, and at another point Schwarzenegger calls his expected child “Junior” for the same reason. But “Junior” is not a neutral term in relation to gender; it’s simply in the interests of this movie to pretend otherwise.

Reed’s pregnancy is carefully kept in sync with Schwarzenegger’s to stave off potential audience objections, and by the end of the movie, Thompson is allowed to become pregnant as well. But one might argue that in this story a woman’s becoming pregnant is only proof that she’s an honorary guy.

The principal source of the humor, it seems, is the usually unacknowledged fact that Schwarzenegger’s appearance and usual screen persona already has certain feminine and even maternal qualities, which this movie literalizes. In manner (i.e., voice and gesture) as well as appearance, Schwarzenegger, like Sylvester Stallone, has more in common with Jane Russell, Esther Williams, Jayne Mansfield, Anita Ekberg, and Dolly Parton than with the principal (and principally lean and mean) macho movie icons of the past — Clark Gable, Spencer Tracy, Gary Cooper, Humphrey Bogart, John Wayne, Clint Eastwood. (Perhaps only Elvis Presley qualifies as a male star who encompassed both physical types over the course of a single career, at least if one gives precedence to sheer mass over muscles.)

If Reitman had the energy and imagination of a Frank Tashlin — who directed Jayne Mansfield in her two most memorable pictures, The Girl Can’t Help It and Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter?, offering an irreverent, cartoony look at this country’s unreasoning taste for opulence in the process — Junior might have offered a satirical development and celebration of this paradox rather than a simple exploitation of its most obvious aspects. What immediately derails such a possibility is a reliance on stereotypical pregnant-wife behavior for most of its laughs — a string of pat cliches designed to mock women more than Schwarzenegger. (The only actor in the movie to show any physical comic flair is Emma Thompson, whose background in stand-up comedy serves her well here in a klutzy part that recalls Elaine May’s myopic character in A New Leaf; everyone else in the cast relies on either the “high concept” or mechanical sitcom sound bites for their quotient of laughs.)

A somewhat sweeter and more innocuous French movie with the same theme, Jacques Demy’s The Slightly Pregnant Man (whose French title translates as “The Most Important Event Since Man Walked on the Moon“), surfaced 20 years ago, with Marcello Mastroianni as the pregnant man and Catherine Deneuve as the bemused wife. That movie shyly backed away from its own premise by having Mastroianni’s condition turn out to be a false pregnancy, and though I suppose Reitman and his writers can be credited for following the same idea all the way through childbirth, this requires so much anatomical fudging and visual hemming and hawing that we never know (apart from a throwaway line about a C-section delivery) which part of Schwarzenegger’s body the infant emerges from or how Schwarzenegger seemingly survives the experience painlessly. (I guess guys are tougher.) The desire of the audience to accept this conceit seems to count for more in the ultimate scheme of things than the faltering efforts of the filmmakers to flesh it out (literally as well as figuratively). The movie wants us to excuse its theme, and so it espouses an overall “reverence for life.” It’s too bad that the filmmakers couldn’t include women in their reverence with the sort of understanding that Mary Shelley showed toward men.