From the Chicago Reader (December 16, 1994). — J.R.

Red

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Krzysztof Kieslowski

Written by Krzysztof Piesiewicz and Kieslowski

With Irene Jacob, Jean-Louis Trintignant, Frederique Feder, and Jean-Pierre Lorit.

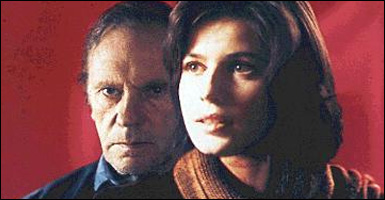

A film of mystical correspondences, Red triumphantly concludes and summarizes Krzysztof Kieslowski’s “Three Colors” trilogy by contriving to tell us three stories about three separate characters all at once; yet it does this with such effortless musical grace that we may not even be aware of it at first. Two of the characters are neighbors in Geneva who never meet, both of them students — a model named Valentine (Irene Jacob) and a law student named Auguste (Jean-Pierre Lorit )– and the third is a retired judge (Jean-Louis Trintignant) who lives in a Geneva suburb and whom Valentine meets quite by chance, when she accidentally runs over his German shepherd.

Eventually we discover that Auguste and the retired judge are younger and older versions of the same man (neither of them meet, either). Another set of correspondences is provided when, in separate scenes, Valentine and the judge are able to divine important facts about each other: he correctly guesses that she has a younger brother driven to drug addiction by the discovery that his mother’s husband is not his real father; she correctly guesses that he was once betrayed by someone he loved — which also happens to Auguste during the course of the film.

With so many different instances of chance, telepathy, and prophecy in Red, one’s credulity is constantly being challenged, but not to the point where the film itself ever threatens to crumble. The coexistence of the real and the everyday on the one hand, the mysterious and the miraculous on the other, is one of the movie’s givens, and much of what is beautiful in Kieslowski’s style stems from its moment-by-moment charting of that charmed coexistence as he cuts or pans or tracks or cranes between his three characters, interweaving and dovetailing their separate lives and daily movements.

What emerges is not a “realistic” world in any ordinary sense, yet it is a fully and densely realized one, and one that has more insight into the world we all live in than conventional Hollywood wish fulfillments, which are no less fanciful in their details. Even the recurring uses of the color red — which seems to be found rather than planted in the various Geneva locations — impress us less as fantasy or invention than as one person’s way of seeing the world, alert to all the feelings and conditions that are generally associated with that color in human interactions: passion, jealousy, pain, injury, fear, embarrassment, love.

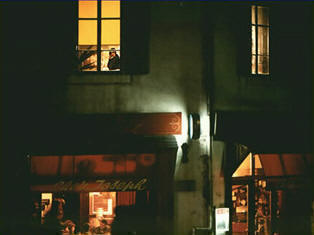

Perhaps one reason why we can accept the strange congruences of Kieslowski’s world even when our rational responses reject them is that the city of Geneva itself and its customary channels of communication and connection help to bring them about. Streets, cars, windows, posters, newspapers, radios, TVs, and, most of all, telephones become the vehicles of casual conjunctions and gorgeous everyday miracles, suggesting that these channels could bring all of us together in ways that we never suspected, even if they usually don’t. Valentine has a jealous boyfriend living in England, and Auguste’s girlfriend in her flat operates a telephone weather-report service periodically used by the judge. All five of these characters rely on telephones as conduits out of their isolation, even if they more often only confirm their loneliness. The remarkable opening sequence traces the phone lines between Valentine and her boyfriend across the English channel, red wires and all. It’s the first of Kieslowski’s many dry and mordant Polish jokes: at the end of this epic journey, the call hits a busy signal.

When the judge is brought to court after confessing to a crime, Valentine learns about it in the newspaper, and when Valentine makes an appearance at a fashion show, the judge learns about it the same way. Even if Valentine and Auguste never meet, their apartment windows repeatedly frame each other’s activities in the streets below. The huge poster advertising chewing gum that we see Valentine posing for is eventually unfurled on a busy intersection; soon afterward, she returns to her flat and finds the lock to the front door jammed with chewing gum, most likely as a result of this poster. It is a car accident that causes Valentine to come into contact with the judge, and it is a busy intersection where Auguste drops his law books while crossing the street; one book falls open to the page that contains the answer to a key question on the law exam he is about to take, a chance occurrence that also happened to the judge many years before.

In the November-December issue of Film Comment, Dave Kehr — in the best critical account of “Three Colors” that I’ve read, pointedly titled “To Save the World” — compares this complex juxtaposition to the cutting between different stories and historical periods in D.W. Griffith’s Intolerance, seeing it mainly in terms of parallel editing. Yet if one concentrates instead on spatial proximities — the proximities between Valentine and Auguste on the same street or in the same neighborhood, or even the proximities between Valentine and the judge, conversing and interacting in their three pivotal scenes — one may also be reminded of Jacques Tati’s Playtime. But neither of these reference points, which concentrate respectively on temporal and spatial continuities, comes close to fully accounting for the intricate web of interconnectedness and the poem of rhyming destinies that Kieslowski finds between three lonely urban individuals, a vision that is at once ecstatic and despairing, tragic and utopian.

This universe of interconnectedness is bounded at one end by total obliviousness (Valentine and Auguste are strangers to one another in the same neighborhood) and at the other by obsessive, gloating attention: the judge spends much of his time listening to his neighbors’ phone calls. When Valentine’s horrified discovery of his snooping persuades him to blow his cover, making the neighbors aware of his eavesdropping, many retaliate by throwing rocks through his window. Between that obliviousness and that obsessive attention loom utopian possibilities of communal urban life as well as the essential and debilitating isolation of all these people, and Kieslowski plays on these dialectical registers as if on a grand organ; the subject of his music is nothing less than human possibility in the contemporary world.

Apart from a few obvious exceptions, masterpieces take a while to impose themselves and be recognized as masterpieces. People often prefer to forget this, but excitement about the first features of Godard, Truffaut, and Resnais in the late 50s and early 60s was not universally shared, nor were their meanings fully apparent the first time around, not even to critics. A lot of proselytizing, discussion, and debate had to take place before they began to take on the status of classics. The same process took place with Bergman, Antonioni, and Fellini; long before these and other filmmakers became canonized and then vulgarized by imitation in American movies (by directors ranging from Woody Allen to Bob Fosse to Paul Mazursky), they were still regarded as controversial and problematic artists, and in some respects they remain so even today — which is why the most recent works of all three, all made many years ago, have yet to be released in this country. (Bergman’s Fanny and Alexander is a six-hour film made for Swedish TV, and the version shown in the U.S. is 105 minutes shorter than the original; Antonioni’s Identification of a Woman and Fellini’s The Voice of the Moon have never been released here in any form.) Nowadays most critics, lulled by outsized studio ad campaigns and eager for the currency that comes with instant recognition, tend to be much lazier than they used to be about grappling with difficult and innovative pictures, and many go out of their way to avoid them entirely. Many of the most important new names in international cinema are missing from the just-published third edition of David Thomson’s A Biographical Dictionary of the Cinema, and the same is partially true for the posthumously completed second edition of Ephraim Katz’s Film Encyclopedia, ratifying the relative inertia of critics happy to stick mainly or exclusively with Hollywood merchandise.

Even after three viewings, Red remains an exquisitely mysterious object to me — one that has grown in beauty and density each time I’ve seen it, without ever convincing me for a minute that I’ve perceived all of its meanings and riches. The same could be said for “Three Colors” as a whole, which has been playing in Chicago in installments since last winter. (It was screened as a trilogy at the Chicago International Film Festival last fall, and the Music Box is thoughtfully providing another chance to see it in sequence by screening Blue and White as a double feature on Saturday, December 17.) I’d say White seems the weakest of the three and Blue the second best, but this comes from seeing them as separate movies; it’s possible that after seeing all three in sequence, I might view all of them somewhat differently.

Another school of thought, and one that’s a great deal more prevalent, says that movies should blow their wad — put up or shut up — the first time around, even (or especially) if you’re a film critic. If this school of thought has a dean, it would be Pauline Kael, and if it has a curriculum, the required movie of the moment would surely be Pulp Fiction. Kael, of course, retired four years ago, but that doesn’t mean that her gospel of instant response and unretractable opinion isn’t fully in force in today’s marketplace; given the planned obsolescence of our culture as a whole, and the preference for light entertainment over any other aesthetic activity, it could hardly be otherwise. In fact, if you turn to the testimony of David Denby, one of Kael’s oldest disciples, writing recently in New York, you might conclude that Kieslowski — “an artificer, perhaps, but not an artist” — isn’t fit to polish Quentin Tarantino’s boots:

“With Red, Kieslowski has completed the trilogy that began earlier with Blue and White, and it would be wonderful to announce that the three films amounted to a major work. (They’ve been hailed as such in Europe and in some quarters in America.) Unfortunately, it’s not so; and, if I’m not mistaken, there’s an element of dismay and put-on lurking in the praise. One senses an illusion close to cracking — the dissolution of a set of assumptions that animates a half-dozen film festivals a year. The truth is, the European cinema has lost its authority. It’s not that there aren’t good films every year. Of course there are (and there may be other good ones we don’t see). But great films are not being made — not the way they were each year in the fifties and sixties — and much of what we see here of French, German, Italian, and Eastern European movies seems feeble or imitative or cultured in a trancelike way that means little to us. A nihilistic pop masterpiece like Pulp Fiction blows away European movies even faster than it does most American movies. For good or ill, American movies are eating the world market, and until new economic conditions emerge for the film business on the Continent, we may have to do without major European directors.”

Given such sentiments, it’s small wonder that Kieslowski recently decided to retire from filmmaking. Assuming that it’s possible to distinguish between economics and aesthetics in the above directive (a frequent problem in writing of this kind), Denby’s authority here rests on a form of telepathy and prophecy that goes well beyond Kieslowski’s. Like Kael before him, Denby is notorious for avoiding film festivals (making it impossible to determine which half-dozen he could be thinking of), so his conclusion that “great films are not being made” necessarily rests on a faith in the critical acumen of U.S. distributors bordering on religious — not to mention an implied reverence for European cinema in the early 50s that I for one would like to see him justify. Of course he’s perfectly entitled to regard “Three Colors” as a failure; what I object to is his presumption of expertise regarding world cinema in general.

In fact, Denby’s entire paragraph reeks of the kind of unearned (albeit confident) authority that governs film culture at the moment. His statement that Kieslowski’s trilogy has been hailed as a major work “in Europe and in some quarters in America” automatically implies that Europe is unified and uniform in praising “Three Colors” while America is not — the sort of assumption one can make only if one doesn’t go to the trouble of checking the facts. A few French critics, for instance, scornfully speak about Kieslowski’s “cinema of Esperanto.” Moreover, Denby’s divvying up of “the world market” between America and Europe excludes the rest of the world as immaterial when it might be argued that a key difference between contemporary film culture and that of the 50s and 60s is the emergence of major filmmakers in Africa, the Middle East, and Asia — not “major” in the sense of Tarantino or Spielberg but “major” in at least the same ballpark as Ozu, Mizoguchi, or Satyajit Ray — and major inroads made by Asian commercial films in the world market as well. And is “cultured in a trancelike way” supposed to refer only to Red and not to Pulp Fiction? Kieslowski has Valentine tell her boyfriend on the phone how much she liked Dead Poets Society. Is this pop reference “blown away” by the equally adoring references to McDonald’s Quarter Pounders in Pulp Fiction?

The words in Denby’s paragraph that most reflect Kael’s influence are the first-person plural pronouns — the royal “we” and “us” in “that means little to us” and “we may have to do without major European directors.” Both support a fundamental cleavage between foreigners and Americans, creating an imaginary rift between foreign and American sensibilities that not even personal pronouns can cross. Perhaps foreigners who regard Pulp Fiction as “their” movie — not to the exclusion of Americans, but in concert with them — are provisionally tolerated in this form of tribalism. But Americans who feel the same way about Red (and I’m far from being the only one) become automatically and irrevocably excluded from the discussion; the very notion of a shared tradition or experience between Americans and non-Americans is deemed inadmissible by definition, unless a popular American export happens to be at stake. In more ways than one, the xenophobic underpinnings of cold-war rhetoric live on (even if multicorporate property rights now commonly take the place of politics) and the growing consequences of this enforced isolation are not pretty to contemplate. If anything or anyone has “lost its authority,” this is the part of the critical establishment that continues to pass judgment on films it hasn’t seen — unless what Denby means by authority is something that comes out of a cash register or sprays bullets.

Born in Warsaw in 1941, Kieslowski is nine years younger than Godard and seven years younger than Truffaut would be if he were alive, but he still can be regarded as a member of their generation, for better and for worse. Though he has described himself as not very religious, and though his main collaborator, Krzysztof Piesiewicz — who has cowritten every Kieslowski film for the past ten years — describes himself as Christian rather than Catholic, the thematic treatment of fate and the worshipful attitude toward young women as Madonna figures in Kieslowski’s films both reflect the preoccupations of a Catholic sensibility that can also be traced through the films of Godard and Truffaut (among other French New Wave filmmakers), as well as those of Rossellini and Hitchcock, two of their key mentors.

In this respect, at least, his films are old-fashioned, and Red is no exception. Valentine is viewed throughout in idealistic and sexist terms, as Denby (among others) has pointed out, and the same could be said of Juliette Binoche in Blue and Julie Delphy in White (though in the latter case, the idealization is complicated by betrayal and treachery, as it often is in Godard’s early features). All these women are treated as mythical and transcendental figures, though in some respects the major male characters are mythologized as well — the dead composer-husband in Blue, Karol Karol (Zbigniew Zamachowski), the Chaplinesque fall guy in White, the retired judge as a caustic, embittered seer in Red. As powerfully and beautifully embodied by Trintignant, this last character may represent the weightiest mythological presence in any Kieslowski film to date.

On the other hand, Kieslowski’s sardonic and absurdist Polish wit infuses his films with a kind of caustic irony that is quite distinct from anything found in the French New Wave. As suggested earlier, Red abounds in poker-faced Polish jokes, from the scene of the German shepherd escaping from Valentine into a church service, to Valentine hitting the jackpot on the slot machine in her neighborhood cafe, which leads a bystander to comment that it’s a sign of bad luck. Much later, the row of winning cherries gets framed in the foreground of a shot while one of the characters passes outside the cafe in the background, comprising not so much a new joke as a reminder of the earlier one. Like so much of Kieslowski’s style and vision, his wit tends to be more interrogative than declarative, which may cause difficulties for viewers accustomed to Hollywood platitudes. The kind of cinema more interested in posing questions than in answering them — the cinema of Stroheim, Preminger, Rossellini, Cassavetes, Rivette, and Kieslowski, among others — is always bound to encounter resistance from critics and others who go to movies in search of certainties, and who often settle for half-truths or outright lies as a consequence. To interrogate the world is to inaugurate a search that continues after the movie’s over, implying a lack of closure that most commercial movies shun like the plague.

The difficulties of judging, of loving, of trusting are central to the lives of all the leading characters in “Three Colors,” and if the burnt-out case of the judge comes to stand in some ways for all of them, this is largely because, like the heroine of Blue and the hero of White, his identity is chiefly formed by a life already lived — and shattered. Whether or not he has experienced a genuine resurrection by the end of Red remains an open question, but there is little doubt that he has glimpsed the possibility of one, much as Julie (Binoche) and Karol (Zamachowski) have before him. Throughout “Three Colors” Kieslowski’s style has been devoted to discovering, exploring, and allowing us to glimpse this possibility. Judging by Red, the more we allow ourselves to experience his style, the more hopeful that possibility becomes.