From the February 3, 1995 Chicago Reader. –J.R.

In the Mouth of Madness

Rating *** A must see

Directed by John Carpenter

Written by Michael De Luca

With Sam Neill, Julie Carmen, Jurgen Prochnow, David Warner, John Glover, Bernie Casey, Peter Jason, and Charlton Heston.

In the Mouth of Madness isn’t John Carpenter’s best horror movie to date, but it may well be his scariest. What makes it nightmarish isn’t so much its premise — a man set loose inside the mind and writings of a crazed hack novelist — as the many elliptical details that the premise occasions: things that go bump in the head, fleeting suggestions of horrors that brush the edge of our attention and perceptions, like the peripheral events in bad dreams.

In this respect, Carpenter seems to have entered David Lynch territory — an unlikely development, but then Carpenter’s career has been full of unlikely developments. In early features like Dark Star (playing this Tuesday at the University of Chicago) and Assault on Precinct 13, he was a playful auteurist making the rounds of popular genres, nodding to masters like Hawks and Hitchcock along the way. After establishing himself as a suspense and horror specialist in Halloween, his first hit, he took an abrupt right turn into gritty (and implicitly libertarian) action kicks in Escape From New York, then virtually drowned in special effects in his remake of The Thing. Prince of Darkness was a welcome return to low-budget horror filmmaking, this time with certain metaphysical pretensions; and in the singular and neglected They Live Carpenter unexpectedly became an angry anti-Reagan pamphleteer, noting how poor people of different races were being goaded into fighting one another by an efficient, smooth-talking ruling class (represented here as aliens) with the right kind of sales patter and media control. Even in Memoirs of an Invisible Man, an uneven effort in which control was effectively wrested away from him by producer-star Chevy Chase, Carpenter was still feeling his way into new kinds of material.

Significantly, throughout these shifts Carpenter never lost the distinguishing characteristics of his earlier phases; these new genres merely constituted a widening pool of resources. In fact, all the stages of his career outlined above are present in some way in his new feature. Carpenter’s interest in certain auteurs comes through when the hero, John Trent (Sam Neill), expresses his preference for “professionals” over “amateurs,” alluding to the familiar rhetoric of Howard Hawks (both on-screen and off), or when Trent tugs at his earlobe, recalling Humphrey Bogart in Hawks’s The Big Sleep. There’s plenty of gritty action here à la Escape From New York as well as special effects à la The Thing, not to mention suspense, metaphysical pretensions, and repeated swipes at the gullibility and conformity of the masses. Carpenter is also exploring new kinds of material, including a literary form of paranoia and a taste for the occult fantasy world of H.P. Lovecraft — purple prose, Poe derivations, and all.

The downside of this development is a certain loss of economy; the tautness that gave both Assault on Precinct 13 and Halloween a pristine, almost minimalist kick is gone. A talented primitive from the outset, Carpenter has certainly taken on more skills and interests over the last two decades, but occasional increases in his budgets have sometimes led to a cluttered effect (The Thing is a case in point). Taking on someone like Lovecraft is tantamount to inviting excess, and Michael De Luca’s script, brimming with Lovecraftian moods and intimations, helps this process along.

The literary paranoia that interests Carpenter is found not in the tales of Lovecraft but in other pulp fiction published during the 40s and 50s — among other pieces, L. Ron Hubbard’s Typewriter in the Sky, Philip K. Dick’s Eye in the Sky, Lewis Padgett’s “Compliments of the Author,” and works by Fredric Brown including What Mad Universe, “Don’t Look Behind You,” “Come and Go Mad,” and “The Angelic Angleworm.” In most of these stories the hero finds himself caught in an absurdist fantasy world that is essentially a literary creation, either his own (patched together by his unconscious mind) or someone else’s. Here he’s buffeted about by the idle whims or bad writing habits of the unseen author-god (in the Padgett story, however, the hero possesses a magical book containing all-purpose maxims explaining how he can get out of various scrapes — until he arrives at the final page, which reads only “The End”).

In two of the Brown stories, the paranoid victim is not so much the hero as whoever happens to be reading the story. In “Don’t Look Behind You” (the only nonfantasy item on this list, included in Brown’s collection of crime stories Mostly Murder) you discover that the narrator-protagonist, a mad printer and counterfeiter, has put together only one copy of the book, and it’s the very one you’re reading; wherever you happen to be, he’s waiting close by with a knife to kill you as soon as you get to the end. And in “Come and Go Mad,” set mainly in an insane asylum, there’s a not-so-faint suggestion that when you get to the end of the story you’ll be just as mad as the hero.

Reminders, if not literal echoes, of these elements are present in In the Mouth of Madness. The movie opens in an insane asylum, where we see John Trent being dragged, kicking and screaming, into a padded cell. Shortly afterward the fatuous floor attendant puts some cheerful Muzak onto the PA system (a song by the Carpenters, no less — a sort of in-joke, possibly to remind us that John Carpenter, no relation, helped compose the score for this movie), which drives Trent even battier. When the music grinds to a sudden halt, Trent seems to experience a series of hallucinations — including a man speaking to him — in a few lightning-fast cuts.

A little later, when a doctor (David Warner) comes to interview him, Trent is in the process of decorating his padded cell and his own face and body with small black crosses. After a little goading from the doctor, Trent begins to explain the events that have led to his present state, and most of the movie consists of this extended flashback. (Readers who don’t want any surprises revealed should check out now.)

As the flashback begins, Trent, a cynical but expert insurance claims adjuster, is hired by a publisher (Charlton Heston) to track down a best-selling horror author who disappeared in New England two months earlier, after completing only part of his much-awaited new novel, In the Mouth of Madness. Sutter Cane supposedly outsells even Stephen King (whose name has a similar ring), and his fans are so hysterical it’s said that his books drive some of them mad. Trent remains highly skeptical, believing all this talk to be a publicity stunt. Yet his life is threatened by a fan wielding a pickax, who proves to have been Cane’s literary agent, and reading Cane later shakes him up considerably (shown in some fine shock effects from Carpenter).

Piecing together portions of Cane’s book jackets, Trent discovers a map that, placed over a map of New England, seems to point the way toward Hobb’s End, Cane’s obscure last address. (As Carpenter pointed out to Bill Krohn in an interview for the forthcoming March issue of Cahiers du Cinéma — an invaluable source of information on the movie — the name “Hobb’s End” has an obscure source in the 1967 British SF feature Quatermass and the Pit.) Accompanied by Linda Styles (Julie Carmen), Cane’s editor, he drives off to New England in search of this village.

When they finally arrive there, after a magical passage that recalls Dorothy’s teleportation to Oz, they find that the village duplicates the settings and characters of Cane’s novels. Eventually they encounter Cane himself (Jurgen Prochnow), typing the final pages of In the Mouth of Madness inside an empty cathedral. Interspersed with these discoveries are a plethora of hints about Cane’s Lovecraftian world — an occult world of ancient gods and primitive rites beneath the mainly placid surface of a sleepy New England town. But as evidence of this world grows and Trent is increasingly entrapped in Cane’s literary world, forcing him to abandon his skepticism about both, one begins to wonder whether the premodernist Lovecraftian universe belongs in the same picture with the postmodernist, self-referential conceit. Each concept yields a number of unsettling moments, but together they produce a scattered rather than a unified effect — and a narrative that moves in fits and starts, impeding the overall momentum.

Part of the problem is that Cane himself seems to have a double identity: Stephen King in the world of Manhattan bookstores, and H.P. Lovecraft in the world of Hobb’s End. The movie repeatedly juggles these identities rather than resolves them. Carpenter also tends to be stronger — that is, eerier — when he sticks to a contemporary setting than when he tries to conjure up a Lovecraftian demonology at several removes. The literary paranoia, which in this picture belongs to the contemporary world, produces most of the film’s cleverness and nearly all of its funniest lines (“You can edit this [book] from the inside, looking out,” for example, and “I think, therefore you are”), while the Lovecraftian iconography mainly seems to emerge whenever the filmmakers’ imaginations are running dry.

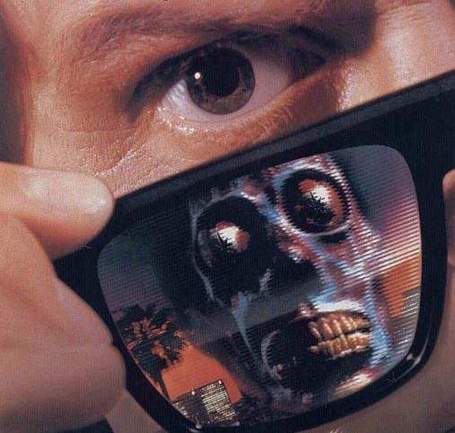

Of course, part of the idea is that Cane is a hack novelist, and that Trent and Styles find themselves trapped in a novel full of horror clichés (ranging from “living dead” mobs to various kinds of gothic imagery). Still, the fresher, less cliched images are the ones that stick in the mind: a glimpse of a nude male prisoner handcuffed to the ankles of an old lady behind a hotel’s reception desk, the all-blue interior of a bus Trent is supposedly riding to safety (created, according to Carpenter, with blue paint rather than a blue filter). Carpenter’s climactic image — a mad (or sane?) Trent, free from the asylum but living in a world gone bananas, sitting alone in a movie theater and laughing at the movie we’ve just seen — at least has the merit of suggesting that the movie’s ultimate joke is not about horror movies but about us, their audiences, who finally become characters in the movie. Lovecraft might have enjoyed this joke, but I doubt he would have thought of it.