From the Chicago Reader (May 19, 1995). — J.R.

Mamma Roma

Rating *** A must see

Directed and written by Pier Paolo Pasolini

With Anna Magnani, Ettore Garofolo, Franco Citti, Silvana Corsini, Luisa Orioli, Paolo Volponi, Luciano Gonini, Vittorio La Paglia, and Piero Morgia.

Who can predict the changes in intellectual fashion over 20 years? In 1975, when the controversial Italian writer and filmmaker Pier Paolo Pasolini was brutally murdered by a 17-year-old boy in a Roman suburb, he was no more in vogue than he had been throughout his stormy career. If any openly gay writer-director was an international star in the mid-70s, it was Rainer Werner Fassbinder, who at that point was spinning out as many as three or four features a year; he died in 1982 after an orgy of cocaine abuse.

Pasolini and Fassbinder were both maverick leftists who often alienated other leftists as well as everyone on the right, and both had a taste for rough trade, but in terms of their generations (Pasolini was born in 1922, Fassbinder in 1946) and cultural reference points they were radically different. The only reason to compare them now is to note how much their reputations and visibility have changed here over the last two decades. In 1995 Fassbinder is much less a household name in the United States than either Jean-Luc Godard or Andy Warhol, the two artists he was most often compared to when he was alive, whereas Pasolini has much more currency. For one thing, nearly all of Pasolini’s features are available on video, and nearly all in their original screen formats — a fact that separates him from Fellini, Antonioni, and Rossellini. (All that’s missing of his filmography in this country are most of the shorts, many of them major efforts.)

It’s unlikely that Pasolini is as important as these three other Italian filmmakers, though as a writer his reputation is well established. (Only a few years ago Alberto Moravia called him “the greatest Italian poet of the second half of the 20th century.”) But he remains a key figure to many major filmmakers. One of the crucial episodes in Nanni Moretti’s recent Caro diario is Moretti’s visit to the site of Pasolini’s murder, and when I once asked the late Armenian master Sergei Paradjanov (Shadows of Our Forgotten Ancestors, Sayat Nova) what filmmakers were important to him, he reflected for about half an hour on why such directors as Luis Bunuel and even his friend Andrei Tarkovsky were too middle-class, then settled on Pasolini as the only contemporary he respected without qualification. Orson Welles, who appeared in a Pasolini short made immediately after Mamma Roma, was surprisingly respectful: “Terribly bright and gifted. Crazy mixed-up kid, maybe — but on a very superior level. I mean Pasolini the poet, spoiled Christian, and Marxist ideologue. There’s nothing mixed-up about him on a movie set.”

As a poet and novelist and in particular as a newspaper writer, Pasolini enjoyed an influence on Italian culture that would be unthinkable for an American intellectual, but scandal followed him there as it followed him everywhere else, and its impact was international. I’ll never forget the strident, hysterical hooting of professional critics at a late-60s New York press screening of Pasolini’s remarkable Teorema, a deadly serious parable about a contemporary Christ figure (Terence Stamp) seducing every member of an Italian household — father, mother, sister, brother, maid — then disappearing, thereby traumatizing everyone in a different fashion. This movie floored me at the time with its brute eloquence as well as its simple audacity, but it brought irate responses from some of my friends. “The trouble with Pasolini is he wants to be fucked by Jesus and Marx at the same time,” one of them said, and she certainly had a point; it’s hard to think of another artist for whom Marxism, Catholicism, and homosexuality were at once so urgent, so alive, and so outrageously interdependent.

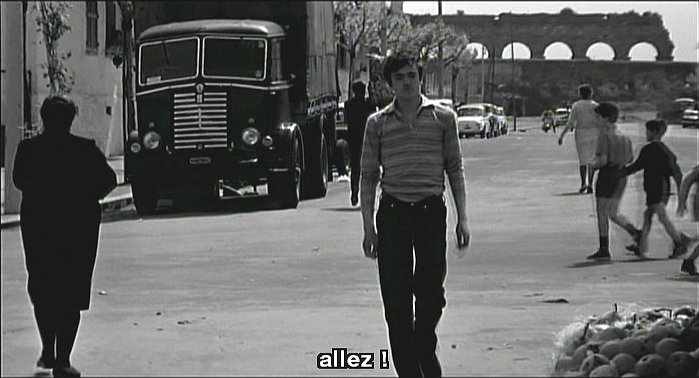

Mamma Roma was Pasolini’s second feature, made five years before Teorema. It’s a good deal less provocative, but it remains one of his better features — and until Martin Scorsese decided to release it, it was the only one that hadn’t been distributed in the United States.

The movie originally came about because the great actress Anna Magnani saw Pasolini’s Accatone in 1962 and decided she wanted to make a feature with him. Pasolini spent three weeks writing a vehicle for her, then began shooting almost immediately. What emerged from their encounter was not entirely satisfactory to either of them, but it remains a landmark in both their careers. A grande dame and something of a prima donna, Magnani is best known today for her films with Rossellini (Open City, The Miracle), Visconti (Bellissima), and Renoir (The Golden Coach), as well as for her 50s forays into Hollywood opposite Marlon Brando (The Fugitive Kind), Burt Lancaster (The Rose Tattoo), and Anthony Quinn (Wild Is the Wind). She was arguably as much an auteur as Pasolini, and the results of their collaboration are a good deal more memorable than his subsequent teaming with Maria Callas on the 1970 Medea.

“In Pasolini’s first films, upward mobility is a descent into hell,” writes critic P. Adams Sitney in his recent book Vital Crises in Italian Cinema. And because upward mobility is all that the title heroine of Mamma Roma really aspires to — trying to find a “better” life for her son than she’s managed for herself, edging him into the lower middle class — this would be a tragic story even if she succeeded. A former prostitute, she joyously attends the rural wedding of her pimp Carmine (Franco Citti) and a respectable country woman in the film’s opening scene: the event signals not only the official end of her servitude but the opportunity to collect her teenage son Ettore (Ettore Garofolo) — who knows nothing about her work — from the countryside and bring him to an apartment she’s found for them in the public housing of a Roman suburb. She eventually finds work selling fruits and vegetables in an open market and, with the help of a prostitute friend, begins stage-managing Ettore’s sex life — steering him away from a promiscuous older woman and single mother — and conniving to get him the right sort of job, as a restaurant waiter, through an elaborate blackmail scheme. But by this time Carmine, who’s left his wife, turns up at her flat demanding that she give him money even if she has to return to prostitution to get it — and threatening to tell Ettore about her past if she refuses.

Pasolini began his filmmaking career as a postneorealist: Citti and Garofolo, like most of the other actors in the film except Magnani, were working-class nonprofessionals whom he more or less pulled off the street. In fact Citti, whom Pasolini had also cast in Accatone, was arrested and put in prison during the shooting of Mamma Roma; Pasolini refused to replace him, holding up the production until Citti was released. When he discovered Garofolo, Pasolini wrote: “It was beautiful, like finding the last verse, the most important, of a poem, like finding a perfect rhyme.” But Magnani came from the petite bourgeoisie, and the fact that her character — “Mamma Ro,” as most of her friends in the film call her — aspires to that class when the actress was actually of it was apparently the source of most of the problems between her and Pasolini.

In Open City (1946) — the film that made her famous, and a favorite of Pasolini’s — Magnani plays a courageous partisan during World War II who’s killed by the Nazis while carrying an unborn child. It’s been noted that if she and her child had both lived, they might well have become Mamma Roma and Ettore; certainly they’re the right ages. But Pasolini’s film communicates an acute pessimism about Italy that makes it as much a critique of Open City as a sequel to it. That pessimism continued to the end of his life and career: ultimately he rejected contemporary settings entirely. For him consumer culture and the obliteration of the Italian peasantry were two sides of the same ugly coin; he set his last picture, Salo, during the final days of Italian fascism and gave his pessimism apocalyptic overtones.

For all its direct emotional power, Mamma Roma is choppy and often somewhat disjointed as storytelling. The viewer is frequently confused about how much time has passed between sequences, and the dramatic confrontations that the story seems to demand and promise — such as a scene between mother and son after he discovers her prostitution — are often left out.

Yet Mamma Roma remains a delicate and at times beautiful work. For all Magnani’s volcanic eruptions in an exuberant bravura performance, this tragedy often seems to have been perceived from a certain distance; the music we hear is mainly Vivaldi (Concerto in D Minor and Concerto in C Major), and Pasolini’s sources for the look of the film came from art history rather than other movies. “That which I carry in my head as vision, as a visual field,” he recorded in a diary during the shooting of Mamma Roma, “are the frescoes of Masaccio and of Giotto — the painters I love most along with certain mannerists (for example, Pontormo).” It’s a tribute to Pasolini’s conception that these classical references seem more natural outgrowths of the story than contrivances imposed on it. When Ettore toward the end is linked to images of the crucified Christ, it’s only after an extended initiation into the brutality of his surroundings has been presented as a calvary. And it seems appropriate that Pasolini’s final image of blighted urban wasteland, a vacant lot surrounded by grimy buildings and a church, should reverberate like an El Greco.